When I was a little girl, my fourth-grade class went on a field trip from my small hometown in South Texas to The Alamo to learn about the cost of freedom. I remember stepping into the darkened entrance of the old Spanish mission, all skinny legs and excitement. The Alamo was a battle site in the 1835 insurrection against Mexico, which paved the way for Texas statehood, and later the trigger of the U.S.-Mexico war that “won the West.” But when I walked out, one important lesson had burned into my mind—in the drive for independence, liberty and democracy, the Mexicans stood in the way. And, as a Latina of Mexican heritage, I was a descendent of the enemy of freedom.

Although the rebels eventually emerged victorious, the Mexican soldiers defeat of the rebels at The Alamo became a legendary wound, one that would later justify state-sanctioned brutality of Mexicans and Mexican-Americans for generations to come. On that day, at The Alamo, I learned that my citizenship, my identity as a Texan as an “American” would always be suspect. Indeed, I have been asked, countless times, “when did you family come across the border,” by people whose great-grandparents arrived in a territory where my people had ranched for centuries.

After I moved away for college and began working as a journalist, Latinos, of diverse backgrounds, often asserted their bona fides as Estadounidenses by citing the number of our uncles, grandfathers and brothers had fought and died in this country’s wars; the Mexican roots of cowboy culture or the intellectual gifts and the contributions to space science, literature, and business made by Latinos, U.S. and foreign-born. Such arguments, which often appeared in media and delivered in speeches, seemed to say, ‘see, we’ve been here, we’re really Americans.’

Whereas people of Irish or Italian ancestry could still be Estadounidenses, their heritage part of the nation’s tapestry, we are the newly arrived, the perennial foreigner, people whose birth rates, buying habits and musical tastes are closely followed for signs of “assimilation” and gauged for their “impact” on the nation but largely absent in the mythology of what it means to be an American.

But then DACA happened. The Deferred Action for Childhood Arrival program, which began in 2012 under President Obama, offered undocumented immigrants brought to the U.S. as children before 2007, a protected status from deportation and the legal right to work and study in the country. Some 800,000 young people who arrived in the U.S. obtained DACA, many more are eligible.

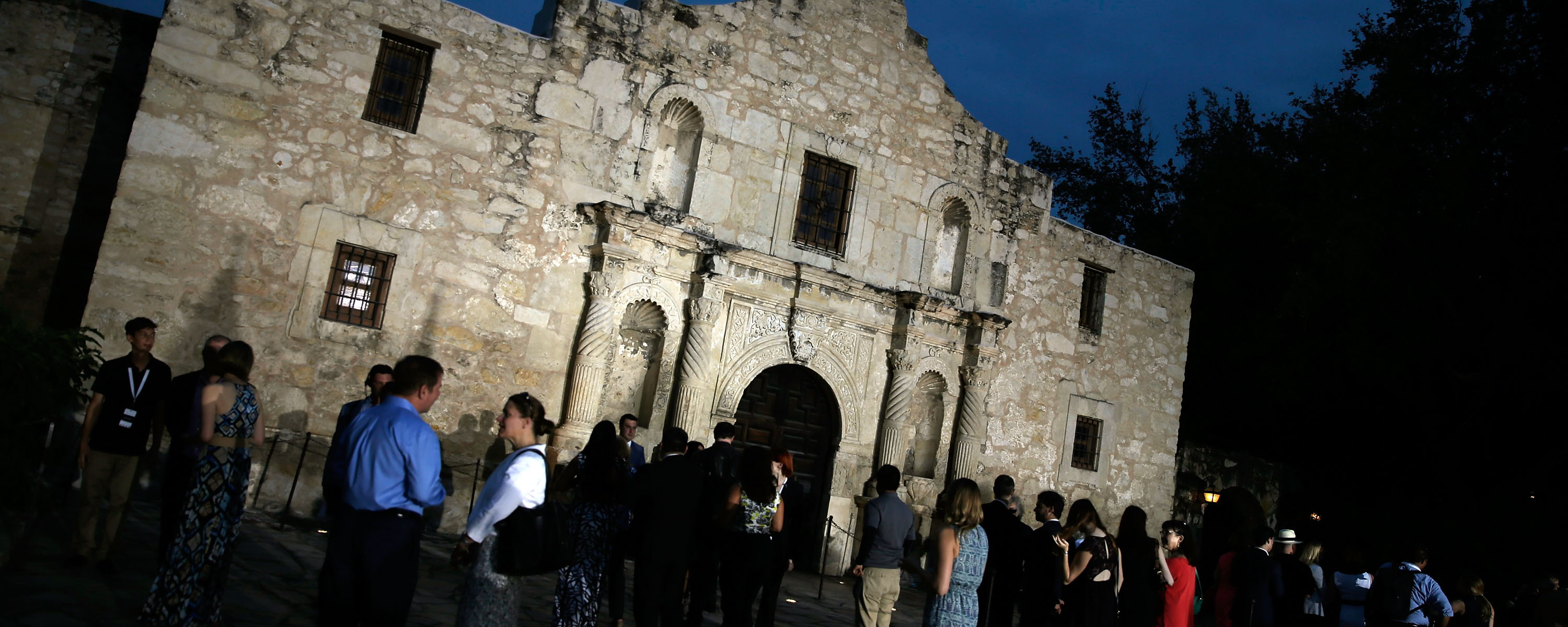

In September 2017, the federal government announced an end to DACA, and I was soon a few blocks from The Alamo, where DACA kids and their supporters gathered less to protest the decision. They didn’t beg or plead for acceptance as immigrants. One by one, they spoke the story of Latinos in the United States, as Americans. “Ellos nos quieren a nosotros como,” began a woman who identified only as Katherine before switching to English,” they want gardeners but they don’t want us.” A woman named Maria also known as Sabdiii yelled, “they don’t want to learn our names. But I am the product of the educational system in the United States.” They held hands with representatives of workers’ groups and Black Lives Matters, and women’s rights groups.

They had wedded their immigrant narrative with the reality of race and class in the United States. Because in Texas, 33 percent of Latino children live in poverty compared with 11 percent of whites do, and Latinos, native and foreign-born earn wages that are approximately one-half those of whites. The decision to rescind DACA was prompted in part by a potential lawsuit by the state of Texas. The politics of the state toward the increasing Latino population and its potential influence was made plain by Evan Smith, co-founder of Texas Tribune who told the “New Yorker” magazine: “White people are scared of change, believing that what they have is being taken away from them by people they consider unworthy.”

In recent months, the worthiness of the DACA kids and the TPS recipients has been gauged by their contribution to the country in dollars and cents. Much like the argument for Latino citizenship that relied on tallying war veterans, their value is calculated by the loss in tax dollars if they were gone, the bilingual teachers, lawyers and future doctors who would vanish. Such calculations are not surprising in a country that where human flesh was one bought and sold at slave markets just five generations ago.

But, in the face of a political climate with its legacy of racism, just a few blocks from where I learned about the cost of freedom, I listened to DACA kids describe achieving dreams as teachers, as students, as people. I heard them describe themselves as role models for the young kids in communities where they were raised. Like the tens of thousands of Salvadorans, who left behind the damage of war, gangs and natural disasters and others who lost Temporary Protective Status, they were offered nothing more than a gasp at a chance. And they did. In an unequal country, where, because of the uncertainty of their status, nothing could be taken for granted, rather than cower and fear over an uncertain future, they seized it. Like real Americans.

They claim this nation, not as a perfect fantasyland of picture books, but in all of its complexity with all of its injustices, as Estadounidenses whose lives are not a plea for mercy but an assertion of their place in this nation. And in listening to them, I reclaimed the part of my citizenship that was lost on that sunny afternoon when I entered The Alamo.

*Michelle Garcia is a freelance journalist. Her work has been published in the Washington Post and the Columbia Journalism Review, among others.