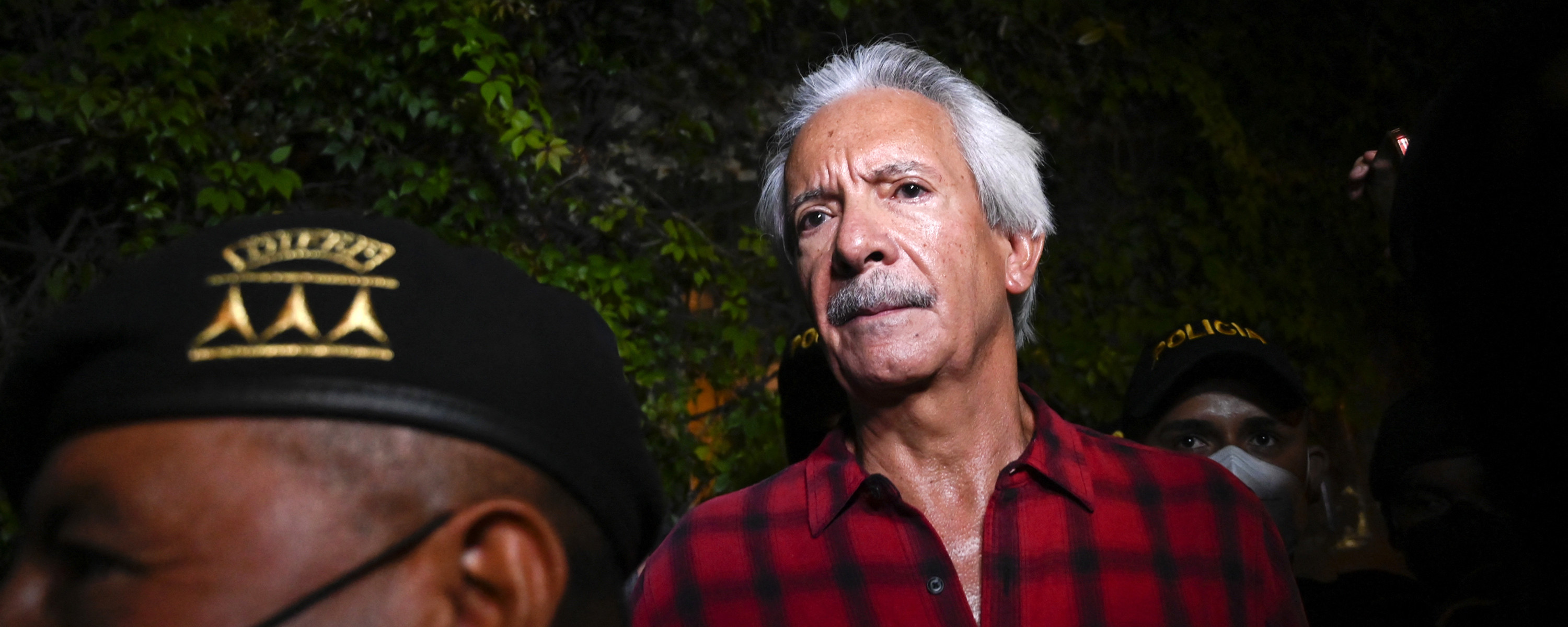

The arrest of José Rubén Zamora, president of Guatemala’s ElPeriódico and one of the most celebrated journalists in Latin America, was carried out last Friday at his home, at the same time that prosecutors and police were raiding his publication’s offices. Authorities have sealed the case and refused to disclose what exactly they were looking for in his home and offices and their accusations against Zamora. International protest forced Special Prosecutor Against Impunity Rafael Curruchiche to make a clarification: “The arrest didn’t have anything to do with his work as a journalist, but rather, a potential case of money-laundering in his role as a businessman.”

What did people think he was going to say? That they arrested him for his publication’s denunciations and investigations of corruption, which unsettles current and former officials alike, including President Alejandro Giammattei and his cabinet, Attorney General Consuelo Porras, and Curruchiche himself? That Zamora was one of the main voices critiquing the takeover of the State by the same dark powers who sacked the International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG), who have mounted cases against judges, magistrates, and prosecutors, including Claudia Paz y Paz and Curruchiche's predecessor, former Special Prosecutor Juan Francisco Sandoval? Would they admit that’s why they detained him? No. Instead, they accuse him of money laundering.

Legislation throughout Central America carries roughly the same definition for the crime of money laundering: the act of administrating, investing, or having money with the knowledge that it came from the commission of another crime. In other words, the attempt to legalize money that was originally illegal, whether it be from drug trafficking or corruption or extortion. There’s another aggravating factor: The crime is so grave that the accused cannot be granted bail and are forced to stand trial from jail.

To accuse Zamora of this crime is to publicly brand someone as tied up with organized crime. To delegitimize them. In the same way Zamora is now being treated, the Nicaraguan dictatorship accused the journalist Carlos Fernando Chamorro of money laundering before seizing his offices. As for me, the Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele accused me of money laundering on national TV while displaying several images of my face.

A few months ago, José Rubén Zamora called me up to offer his solidarity to both me and El Faro, the publication I direct, for the multiple audits we’ve gone through, which had been ordered by the Salvadoran Treasury Ministry in an attempt to build cases of money laundering or tax evasion against us. His decades-long experience in a country like Guatemala, where he’s never stopped denouncing an ever-worsening political climate, have exposed José Rubén and ElPeriódico to various audits of this type. It’s the way those who wish to silence us operate. He didn’t give me any advice or consolation on the call. But he did offer to let me stay at his home, and said that, ultimately, those who accuse us of these crimes in order to cover up their own will one day end up behind bars. Paradoxically, he’s the one who is now a prisoner.

He, who for years has denounced his country’s politicians and generals for misappropriating funds, for obtaining them illicitly and then laundering it, has now ended up in jail. The corrupt and powerful people he denounced still walk free.

Central America is living through a darkening democratic backslide in which those in power are concentrating ever more control at the expense of the constitutional rights of their citizens. The worst example is Ortega’s dictatorship in Nicaragua, followed by the millennial authoritarianism of Bukele in El Salvador, and then Giammattei, who is flanked by Guatemalan narco-politicians, oligarchs, and generals.

In all three countries the institutional backslide goes hand in hand with scandalous corruption and the lack of counterweights or accountability mechanisms. In these conditions, journalism becomes the last levy holding off unpunished abuse, through investigations, denunciations, and critically questioning the exercise of power.

Both the head of the Public Prosecutor's Office, Consuelo Porras, as well as Curruchiche, the prosecutor who ordered the arrest of Zamora, have been signaled in Guatemala and internatinoally for acts of corruption, plagiarism, and interfering in anti-corruption investigations. Both were named in the Engel List, and neither has hidden their intent to take revenge on the justice system actors who, in the CICIG years, tried to clean up corruption in Guatemala. On the day of Zamora’s arrest they also ordered the capture of prosecutor Samari Gómez, a member of the Special Prosecutor’s Office that Juan Francisco Sandoval, who is now an exile, once directed. There are 24 ex-prosecutors and judges who have been exiled by the persecution of Giammattei, Porras, and Curruchiche, and five more facing trial in Guatemala. It’s the vengeance of the old system against those getting in the way of the total cooptation of the justice system. That it is them at the head of the persecution against Zamora says a great deal about this process.

The story of José Rubén Zamora isn’t, lamentably, an isolated case in the region. Over the past year in Guatemala we have had to denounce judicial persecution of an array of other journalists —Carlos Choc, Anastasia Mejía, Juan Luis Font, Sonny Figueroa, Marvin del Cid, and Claudia Méndez, to name a few— against whom old, exhausted judicial cases were being reopened.

In Nicaragua, two journalists and six people tied to newsrooms are being held prisoner in Ortega’s prisons. One of them, Miguel Mora, has been on hunger strike for forty eight days to protest the torture to which political prisoners are subjected. A large number of journalists, including Chamorro, have left for exile. The closing of newspaper La Prensa through the seizure of the paper and the capture of its owner has left Nicaragua without any print media. Ortega's police closed seven Catholic radio stations because they criticized the dictatorship.

In El Salvador, dozens of journalists are being spied on, persecuted, harassed and defamed by Bukele and his spokespeople. At El Faro alone, The Citizen Lab found that 22 of us had our phones infected with Pegasus, a surveillance system capable of activating the camera and microphone on your phone at any moment and extracting all the information from your device. We’ve lived through stalking, smear campaigns started by Bukele, social media lynchings, threats, and surveillance by drones in our houses. One of those little devices, after staying a few meters away for its first visits, managed to smoothly enter through the window of my study and then float, with impunity, a few feet away from me. After our investigations revealed the negotiations between the Salvadoran government and the gangs, the ruling party legislative bloc approved a gag law criminalizing with up to 15 years of prison the journalistic publication of anything about gangs that ventures outside the limits of official discourse.

The ultimate goal of the authorities in all of these Central American countries is the same: to delegitimize us and silence us so that we stop investigating and publishing acts of corruption.

It’s no coincidence that, the Monday after the capture of José Rubén, Curruchiche’s office ordered the publication’s bank accounts frozen. Without money they won’t be able to buy paper, let alone pay their employees. Without money, the most important publication in the recent history of Guatemala will wither and die, its founding member sitting behind bars.

The Guatemalan authorities will think that they’ve gotten rid of a problem. But the truth is that they’ve caused a far bigger one: They’ve awakened an international protest of journalists, free press organizations, and governments. No one believes that José Rubén is a money launderer, or thinks that the Guatemalan justice system is capable of giving him the minimum guarantees for his defense. The Giammattei administration has assumed the image of what José Rubén calls a kleptocracy, one that’s dedicated to plundering the state, and thus, needs to get rid of its critics.

Today, those governing Guatemala have created a prominent political prisoner before the eyes of the world — and those of a Central American journalistic community tired of the attempts of the corrupt to silence us. My solidarity with the Zamora family, and with all of my colleagues in the region.

*Translation by Jared Pace Olson.