This second chapter on the origins of MS-13 was published by El Faro in Spanish in August 2012. Read chapter one in English here.

The helicopter roar is a blessing. Silence between each series of blows would have been more chilling, and the impact of each one even more brutal. If there had been silence, the onlooker would have filled it with the imagined sound of truncheons crashing on the knees, torso, and arms of this Black man rolling on the floor as three police officers beat him. One of them stands with his legs apart like a baseball player, lowering his center of gravity making him able to beat the man harder and with more control. One thump, then another, and another. A pause, then again, a succession of three more blows landing on the legs of this sack of meat as he tries to sit up, disoriented. Another pause for breath, then seven more hits.

In the television images there appears to be a total of 56 blows. Were it not for the helicopter in the recording, filling the silence with its deafening hum, one could even imagine the sound of bones grinding just before they break.

* * *

The video of the attack on Rodney King began to circulate globally in 1991. A 25-year-old Black man, formally incarcerated for robbery, King had been drinking that night and refused police orders to stop his car, fearing a return to prison. The beating was recorded by a bystander and became news on five continents.

The clip was immediately held up as an example of the brutality and racism of the Los Angeles police, who had enjoyed political freedom to beat or shoot their victims since their successful clean-up of the streets in 1984. Fifteen officers were present as King was beaten for over ten minutes. Not one lifted a finger to stop what was happening, and only four of these officers —the one who used the truncheon, and the Sargeant immediately in charge— were brought to trial.

The verdict was made public one year and two months later, on the afternoon of April 29, 1992: innocent. A jury comprised of ten white people out of twelve did not consider the video to be sufficient evidence of excessive force, and charges were dropped.

On the streets of Los Angeles, and especially in the suburbs of South Central and South West, the news sparked rage. What began as small groups of Black neighbors shouting on street corners later spun out of control, with shop windows smashed and insults thrown at white bus drivers passing through the area. After just a few hours, southeast Los Angeles was in flames. For the following three days police were forced to retreat from whole neighborhoods amid widespread looting and street violence. Gas stations, stores, and whole buildings were set alight. Firefighters registered a total of 7,000 fires across L.A. County during the disturbances.

Amid the chaos on the afternoon of the verdict, a helicopter carrying a television crew captured images that, following the beating of King, appeared as a graphic eye-for-an-eye: from their homes Americans could watch as six Black men forced a cargo truck to a halt at the intersection of Florence Avenue and Normandie Avenue, and dragged out its driver, a white man named Reginald Denny. They threw him to the ground, turned him over, began to kick, and took a hammer to his head. Finally, when he was already unconscious, one of the attackers crushed his skull with cement brick. They then began to dance around body of Denny, who miraculously survived the injuries.

For this macabre dancer, the detail was insignificant. He was a violence professional, dressed in an oversized white shirt, baggy pants, and a blue bandana around his forehead. He was a member of the Eight Tray Gangster Crips gang, one of the many groups in Los Angeles who were affiliated to the Crips.

While authorities deployed the National Guard, moving from surprise to a plan to tackle the disturbances, three consecutive days of race riots set the perfect stage for Los Angeles residents who already lived outside the law. Not only did Black gangs —the Crips and Bloods— make use of free reign over their territories to come together and attack other ethnic groups; Latino and white gangs led looting across the city and took the chance to settle debts with enemy gangs without the inconvenience of police presence. When the army regained control of the streets on May 2, there had already been 53 murders. One third of victims were Latinos.

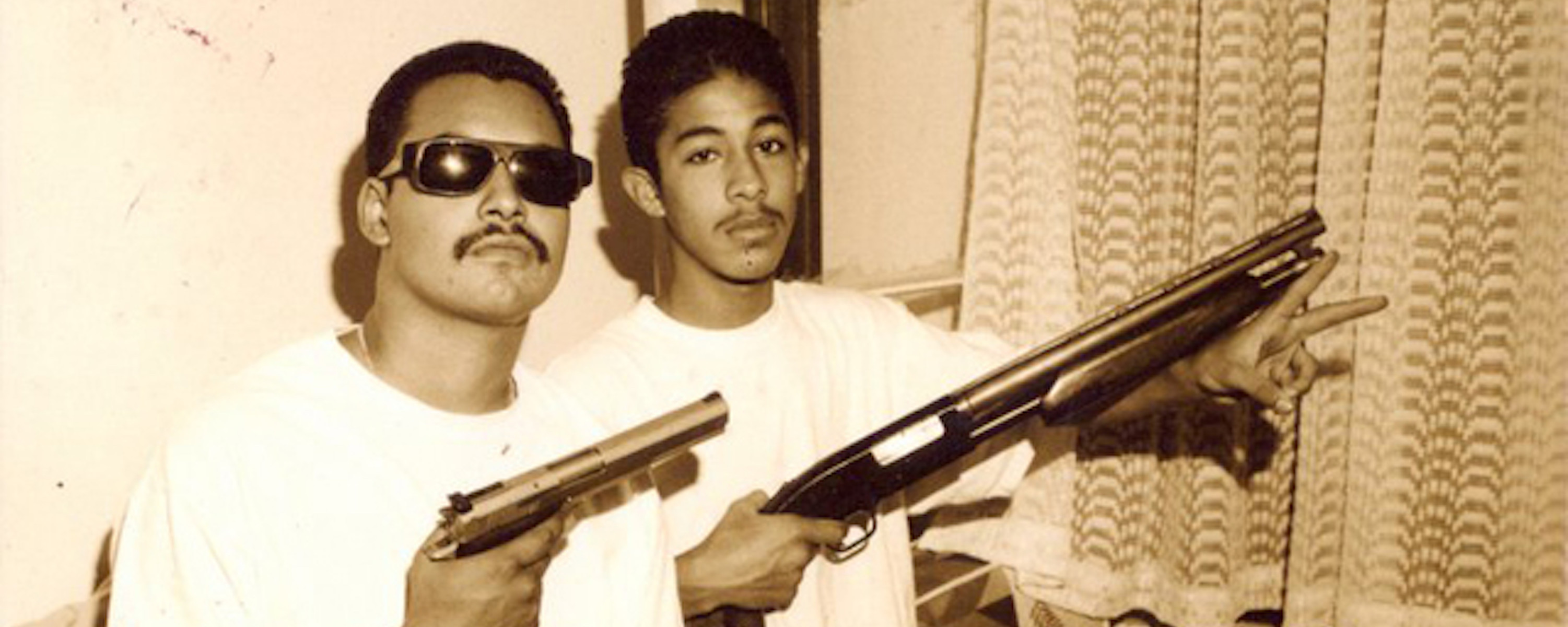

Half of those arrested during the riots were also Latino. One arrestee, detained for his participation in one of the thousands of lootings, was the skinny, unflinching leader of the Fultons, the Mara Salvatrucha clique from the San Fernando Valley. His name was Ernesto, and his nickname Satan.

* * *

It was his first time in prison, but Satan knew what —and who— to expect.

For some years the Mara Salvatrucha had included a number in their name, which among the gangs of southern California means everything: 13. Nowadays many other gangs from Los Angeles and the vicinity, including some of the oldest —Florencia 13, Artesia 13, Norwalk 13— use it at the end of their name. It symbolizes the thirteenth letter of the Spanish alphabet: the M. The number demonstrates loyalty — and submission.

In the late 1950s in the Deuel juvenile correctional facility in Tracy, near San Francisco, a dozen mostly Chicano teenagers from different gangs decided to create what they saw as the ultimate gang. It would incorporate the most notorious young criminals, and they would come to control the facility by force, as well as any other facility they were sent to. Even though they were all underage, many charged with only minor crimes, their ambition was absolute: they called themselves the Mexican Mafia.

Soon their criminal records were stacked with murders they had committed in every prison they were sent to. By the early 1970s their fame, brutality, and organizational control had extended throughout the California prison system. With only about thirty members, drawn from different Latino gangs of southern California, the Mexican Mafia ruled over prison courtyards, terrorizing almost every Latino gang in the state, all of whom knew themselves to be destined for their dominion.

It was as if in prison the final judgement awaited you, and the Mexican Mafia had stolen the gates to hell. Among gang members it became enough to refer just to their initial, M —la eMe— to conjure their influence.

Beyond that, for almost a century Californian prisons have been a cauldron of racial hatred, with gangs continuing their street battles on the inside. To gain the protection of the Mexican Mafia against Black gangs, for example, Latino gangs from southern California gradually began to identify as Sureños, or Southerners, incorporating the number 13 into their identities and paying the Señores money. The prisons rule the streets because the streets fear the prisons. Eighteenth Street, also known as Barrio 18, are also a 13 gang, despite not using the number in their name.

From the mid-1980s various Mara Salvatrucha cliques began to call themselves Sureños. They swore loyalty and paid tribute to the eMe, as their leaders began to fall into the hands of the law, into juvenile detention or county and state jails. The first to enter eMe territories defenseless suffered the violent consequences, but by the end of the decade the whole gang had come to understand that the protection of the 13 was necessary.

In the words of one woman known as Chele, who lived through those convulsive years in the Mara, “it was like different innovations began to spread. No-one gave the order, nor was there any general meeting to agree on it. It was simply that, over a few years, we began to incorporate the 13, and we all became Sureños.”

By 1992 the Fultons were already Sureño, and Satan knew that the Señores awaited him in prison. As the leader of his clique, it was Satan who was responsible for collecting monthly payments that would go to the eMe. The money came from extorsion, or drugs sales made by the clique’s members, and was then given during a Mara general meeting to one member who was responsible for giving the Mexican Mafia the whole gang’s payments. Month after month, without fail, a tithe to hand over with downcast eyes. Violence is just one of two languages spoken by the gang, the one that is heard loudest from the outside. The other is money.

But Satan also knew that, even as a Sureño, it was a bad time to be entering eMe territory.

The rule was that his physical security would be guaranteed between prison walls, because under the eMe’s rule a ceasefire existed between all Sureño gangs, including those who were enemies on the streets. In Californian prisons, under the strict paternal gaze of the Mexican Mafia, members of the Mara Salvatrucha and 18th Street, for example, share cells and patios without a problem. That is what is known as obeying the southern truce.

But there are exceptions to the southern truce. The Mexican Mafia protect, but they also punish. And in the early 90s the MS-13 were submitted to constant punishments for rule-breaking: for late payments, for killing someone they shouldn’t have, or in a place that they shouldn’t have. The green light that permitted or ordered the Sureños to punish in the name of the Mexican Mafia was given often in those years, against MS-13 troublemakers. Sometimes things turned against a specific clique; other times, it was against the whole Mara Salvatrucha.

When Satan entered the prison for the first time, the green light was on the Mara, which in the streets would mean people looking for you in order to beat you, or kill you. If you’re lucky you might be able to slip away, but in prison that light shines with all its strength, and there is no escape. At the police station members of other Sureño gangs had already given him a first beating; the first message from the eMe. Arriving at county jail, things got worse.

“With the green lights it’s not like they tell you, ‘Okay, we’ve told you once, we’re leaving you with broken arms and that’s it’. If they beat you up the guards would take you out of your cell and put you in another, but in that cell they’d beat you too. And that would continue until they sent you to hospital. It got to the point where they put all the Mara homeboys in the same cell, all of them with their black eyes and broken hands.”

He only had to get through two months of this punishment routine. In early July, a well-timed measles outbreak meant he spent his third month at the hospital while his homeboys continued to take daily beatings in county jail.

Three months later, on October 7, a soccer match would further complicate things for the Mara. El Salvador played a friendly against Mexico in the Coliseum, the prized stadium where Reagan had inaugurated the 1984 Olympic Games. Three months prior, on July 26, there had been another friendly in San Salvador’s Cuscatlán stadium, where Mexico won 2-1. This time, El Tri won 2-nil. But the most important thing was not the score, nor what happened on the pitch. During the match a Salvadoran fan in the stands burnt a Mexican flag in front of the ever-present television cameras. The man living these 15 minutes of fame was an MS-13 homeboy known as Squirrel.

Squirrel’s fame cost the Mara greatly. The eMe, who boast of themselves as pure Aztecs and say that since the 60s only those with Mexican blood have been admitted, felt directly offended by the gesture and responded furiously. From the maximum-security prison of Pelican Bay, where most Señores do their time spending 23 hours a day alone in small cells, they sent final orders: the Mexican Mafia gave the green light, and it was open season on any Salvadoran from southern California. Not just members of the Mara Salvatrucha but any Salvadorans in the area. Although it was for just a few months, the flag burning provoked the biggest green-light period ever seen in California.

“They gave their green lights for dumb stuff so that all the Sureños would turn against us. But they were making a monster. Nowadays they don’t give the green light against us so easily, because now we’re strong, even strong against the Señores. They know that if that strength rebels against them they will be weakened straightaway. The Mara Salvatrucha are very well-known now”.

Nowadays Satan and other members of the MS-13 in Los Angeles like to say that that era, with its constant stream of green lights, made them stronger.

* * *

On one morning in 1998 former kickboxing champion William “Blinky” Rodríguez woke with an unexpected call. It was Danilo García. Danilo was known as Big D, and was a veteran member of the Mexican Mafia; some even say he was one of the founders of the eMe. He’d spent most of the past 31 years behind bars, only leaving Los Angeles County jail for a few months.

Blinky knew him well. Big D was 13 years older than him, but they had both grown up in the San Fernando Valley and their paths had crossed in the valley’s parties and bars. They stemmed from the same roots. Blinky says that in the 70s he dreamt of Big D. In the dream, the mafia leader turned to Christianity, and together they embarked on a kind of Evangelical crusade. A few months later Big D was out on parole, and Blinky told Big D his dream. Big D kept his reaction to giving the ex-champion a wary look. Blinky accepted silence as a reply, probably grateful that Big D did not order him dead.

Over a decade passed before they spoke again, so when he called in the middle of the night, Blinky Rodríguez hardly recognized his voice.

“It’s Dano…. This is Big D, man!”

“Hey, Big D… what’s happening?” he managed to ask, still half-asleep.

From the other end of the line, Big D’s voice was ecstatic and euphoric:

“Jesus Christ is happening!”

* * *

“Is the man in the middle chair (Augusto) Pinochet?”

“Yes! He was called Pinochet Ugarte. This is us in Pinochet’s palace in Chile. Benny, Fumio Demura, and me. I was the karate world champion, man! We traveled the whole country doing shows.”

The newspaper clipping from El Mercurio is better preserved than its 1982 date would suggest. In the black and white photo the Chilean dictator is smiling, dressed in civilian clothes, hiding his squinty, weak eyes under his signature sunglasses. He is in the palace hall at La Moneda, sat with three stocky men in ties and suits. The headline reads “the invincible karate fighters”, and below the photo is written: “Chilean President Augusto Pinochet welcomes karate champions Blinky Rodríguez, Fumio Demura, and Benny Urquides”.

The photo is inside a folder crammed with clippings, posters, and whole magazines with Blinky on the cover, or which detail his career as a karate fighter and martial arts expert. It’s clear that in the 70s and 80s, William “Blinky” Rodríguez was a celebrity.

His fighting style was clumsy, ostentatious, and relied little on technique. But it was an era where the line between fight training and official martial arts rules was blurred, varying from one match to another, and amid this fever of fusion and innovation, he made a name for himself. Together with his brother-in-law, Benny “The Jet” Urquídez, considered by some the best mixed martial arts champion ever seen, Blinky traveled the world participating in exhibitions and fights: the Netherlands, Japan, Brazil…

At the San Fernando Valley office of Communities in Schools, the NGO Blinky opened in 1995 specializing in prevention and intervention in gangs, the walls are plastered with memories of those good times. “I had more hair,” jokes the shaven-headed 58-year-old.

The photos and trophies in Blinky’s office are not just decoration; they are a declaration of identity. Gang members who ‘cool off’, who stop committing crimes and killing people, managing to distance themselves from their clique and their clique’s business —those who are able to— usually have the appearance of a retired fighter, still ready to join a war if they were needed. Holding onto some of their ferocity is a way of protecting themselves. Blinky was never a gang member, but he connects with that philosophy. He is a retired fighter who works with former gang members, men who themselves have the appearance of retired fighters, too.

He is also a religious man. Extremely religious.

On February 3, 1990, at around 1 in the morning, gang members from the Pacoima area shot a young man, Bobby Rodríguez, from a moving vehicle. He was 16 years old, and died from a bullet to the chest. Bobby was a better athlete than student, and tended to dress like a gang member. Many of his schoolmates claimed he was, though he had no criminal record. He was one of Blinky’s sons.

News of Bobby’s death did not appear in newspapers, but what did make the news was that Chuck Norris, Blinky’s training partner in the 80s, would cover part of the funeral costs. Former fighting champions, film stars, and gang leaders from around the San Fernando Valley, as well as Bobby’s friends from school and the streets, all attended the funeral. There, over his son’s coffin, they approached Blinky and offered him vengeance. The fighter says he sought refuge in his faith to decide what steps to take. He stopped them and invited them to visit him a few days later at home, to pray.

Whether out of obligation, or because they were fascinated by this bulky man who had attained fame and fortune with his fists, six of the gang members came to the meeting. They were from different barrios, different gangs. It was the first of many meetings held over the coming months. At the meetings Blinky would preach but there was also time for them to discuss life on the streets, and the problems each gang was having. Without knowing it, Blinky had begun his transformation into a mediator. Now when he speaks of his son’s death, he calls it “the seed”.

* * *

When he began meeting with gangs, Blinky Rodríguez called on Big D for help. After his religious conversion, the mafioso had managed something that, even today, seems impossible: to leave the Mexican Mafia and stay alive. In honor of his years of service to the eMe, the Señores had let him go; he was allowed to distance himself with no hard feelings involved. Despite his new life as a preacher, Big D still commanded huge respect in the gang world of southern California.

He was just what Blinky needed. The former fighter knew that to continue his work he would need more than just to pray intensely. He couldn’t take more ambitious steps without having someone beside him who could speak to the gang members in their own language. And most importantly, without someone who could explain to the eMe that Blinky did not intend on harming them. The gangs of Los Angeles and the surroundings are the water on which the Mexican Mafia’s economic interests set sail. Any breeze that ripples those waters attracts the Señores’ attention.

Big D held meetings and got people’s backing. The meetings were moved from Blinky’s house to the Jet Center, the huge gymnasium that the former fighter had established in the early 80s, together with his brother-in-law Benny “the Jet” Urquilla. The number of gangs participating grew, as did the impact of what was being said.

Blinky remembers one time that a young man, a 25-year-old gang member, came to one of the meetings with a bruised face and marks all over his body. He said that a group of gang members from another barrio had beaten him up. His homies were with him; they wanted to know who had done it, and why. They spoke in thundering voices. They wanted justice, street-style. The feeling of disrespect bore a hole in their chest, and they wanted to fill it with someone else’s pain. Suddenly, from the back of the gymnasium, a small gang member cleared a path between the others, came forward and said, “Hey, they didn’t jump you, I did it”.

The perpetrator was less than five-foot-three, and looked around 16 years old. He claimed that the other gang member had disrespected him by insulting him in front of his girlfriend. “I took care of you, on my own”, he said. And Blinky says that the other man saw in his face that it was true.

“The people from his barrio took him. But if that situation hadn’t cleared up, someone would have been killed!” says Blinky.

“Because of a lie told by someone who didn’t want to look like a coward, man. Before we held those meetings, if anything happened they would get in a car, and boom! They would get anyone, because there was no communication. It doesn’t matter if there’s cell phones, newspapers… there’s no communication! Even today on the streets everything could be falling apart before one person talks to another.”

For two years, the Jet Center was the epicenter of gang life in the San Fernando Valley, a swarm of residential districts and suburbs inhabited by over 1,800,000 people. Every Sunday Blinky and Big D would resolve conflicts quickly, and preach to the gang members: “Look, it’s not about what you’re doing to the others, it’s what you’re doing to yourself. You’ve got your own mother trapped, man. Your mother and your homeboys’ mothers have to hide behind the curtains and your sisters can’t go and play in the streets, man.” They coined a catchphrase: “No mothers crying, no babies dying.”

They managed to get the gangs from around the valley to reach a non-aggression agreement between them. A truce.

From 1992 there seemed to be an epidemic of gang truces on the streets of southern California. After the disturbances triggered by the Rodney King case the two biggest groupings of Black gangs in the state, the Crips and Bloods, had opened a process of dialogue and managed to get many of their affiliated gangs to stop confrontations. On top of that, in the parks of Los Angeles and the vicinity there were also sporadic meetings of Latino gangs, where important members of the Mexican Mafia called for unity and peace between Sureño neighborhods. The eMe banned Latino gangs from doing drive-bys —shooting from moving vehicles— as well as attacks on the families of enemy gang members. The police were taken aback, wary — almost as much so as the leaders of many of these gangs, who after decades of war among themselves were now hearing the Señores speak of holding fire and mutual respect.

With peace confirmed in the San Fernando Valley, the meetings were moved into an open area. On the night of Halloween, 1993, almost 300 gang members, including the leaders of more than 70 different gangs from around the Valley met for the first time in Pacoima Park, under their neighbors’ gaze. And the police’s too, who refrained from breaking up the meeting that day, and on following days. Nor did they make any arrests, even though various gang injunction laws were in effect that prohibited three or more gang members with a criminal record from meeting in public.

Blinky informed the authorities of what he was doing, and with the support of other organizations like the YMCA or local churches, he gained a tacit promise of tolerance from police chiefs.

Over the coming weeks there were basketball games held over Sunday in Pacoima park, as well as soccer, baseball, and a kind of American football with no protections that families in the United States often play together. Gangs formed their own teams and played each other — with no arms, nor beatings. It was as if they’d turned into a TV ad for the Boy Scouts of America.

There were representatives from all the big gangs present at these sporting tournaments, except for the Mara Salvatrucha. The other barrios, who still held onto their Chicano racism, did not want them there. But Blinky and Big D insisted. They knew that if the MS-13 weren’t at the meetings they wouldn’t achieve any peace agreement with them. Or, a bullet from them or directed at them would break everyone else’s peace. They spent weeks warming the leaders of gangs from the area —Langdon Street, Dead End Boys, and Eighteenth Street Northside— to the idea. The Sureño gangs knew that just one year earlier, the eMe had given the green light against every Salvadoran in LA county. It could be said that hating MS-13 was seen as a good thing.

In the end, the argument won out that Latinos should be united. Big D spoke to Satan, leader of the Fultons, extending a hand to him on behalf of the rest of the gangs. He assured him that the meetings in Pacoima Park had the go-ahead from the eMe, and convinced him that the truce was good for everyone. Satan was suspicious, but agreed to talk it through with his homeboys. He called a meeting of his clique and suggested going to the meeting and joining the truce. The first reply he got back was a challenge: “There can be peace with other barrios, but never with the 18.” It was a struggle for him to convince his homeboys: they agreed, but they were not surrendering. They were not renouncing their hate.

They went, arriving armed and defiant. Ten of their homies waited outside, ready to shoot. Satan went in without a gun, accompanied by a small group of the Mara Salvatrucha. He was wearing a hat reading “Fuck Y’all,” which he’d picked out especially for the occasion. The organizers asked him to take the hat off because it was an insult to the other gang members, and he did. He walked down the passage his enemies had cleared for him, returning people’s looks, and arrived at the front ready to listen. Satan knew that not even the fighters in the Fulton were interested in being completely alone and in open conflict with the rest of the gangs in the valley.

“We made the truce. We said something like: ‘Okay, if my homeboys come to your neighborhood and you beat them up or anything like that, this is all going to be over, we’ll go back automatically. But if you see my homeboys and you show them respect, we’ll show your homeboys respect too, when we see them.’ Because it’s like, you’re not going to respect someone who comes to your territory with their shirt open, showing off their tattoos, like a traitor. If they show you respect, you show it back. That’s how it works.”

During the meeting in Pacoima Park someone tried to complain to Satan about a fight that a member of the Mara had been in a few days before. The Fulton leader stopped him immediately: “Talk to me about what happens from today onward.”

Blinky claims that after that meeting there was not a single gang-related murder in the San Fernando Valley for a whole year. But that’s not all true.

On the night of September 17, 1994, a young, 25-year-old man named Daniel Pineda was killed. He was heading home after watching Julio César Chávez beat Meldrick Taylor once again for the featherweight world championship. He parked next to a park to drink a few last beers with his friends. A pair of gang members approached him, recognized him as an enemy, and stabbed him. Pineda, known as Droppy, worked as a painter and was an active member of the San Fers, a gang from the valley. And he was married to one of Blinky’s nieces. It was as if a Hollywood screenwriter had decided to load the story of the end of the truce with familiar irony.

Blinky holds that his nephew-in-law’s murder was the first killing in 11 months, since the Pacoima Park truce. But police records show that nine gang-related murders had taken place already that year. In any case, it was less than the 15 over the same time period during the previous year.

The truce had borne some fruit, but it began to lose strength. Representatives from only 18 gangs came to the Sunday meeting the following week. Although Blinky and Big D continued to hold the Pacoima Park meetings until April 1995, they knew as well as the gang members from the valley that the dream was falling apart. No-one said it openly during a meeting, but they all saw the signs that the Mexican Mafia were tired of supervising from afar, and wanted to take full control of things in the San Fernando Valley.

Gunfire with a Silencer

“Blinky, we know that in 1993, while you were doing those things in the San Fernando Valley, other similar meetings were being held in the city of Los Angeles. You didn’t coordinate those meetings. It was the eMe.”

“Look, I’m careful not to say that name. I don’t use it.”

In California the eMe are not mentioned by name. Nor are their soldiers, chosen from the ranks of Sureño gangs to carry out orders and get their hands dirty carrying out hits for the Mafia. Nor their carnales, as the true members of the eMe, this ultimate of gangs, are called, the elect chosen in secret from among the most established and influential gang members of southern California. It is the same in many Salvadoran communities, where members of the Mara Salvatrucha or 18th Street are timidly referred to as los muchachos (“the boys”), to avoid making anyone uncomfortable nor to summon them with their name. In Los Angeles the Mexican Mafia and their men are referred to as “the Señores”, with reverential respect, or people avoid any talk of them whatsoever.

“Okay, we won’t use it.”

“There was a difference. I don’t want to seem like a religious fanatic… but I am a fanatic. That’s why I’m still here doing this work 22 years later. I’m here on a knife’s edge every single day. Look, I don’t tell people everything we do…

Blinky lowers his voice, as if sharing a secret.

“…because they get jealous. It’s sad, man. Here in Los Angeles the government want to make everything we do look pretty, so it sells. Nowadays this work has become sexy. But it’s a work of art, man, it requires you to break a sweat.”

“What’s the difference with what was going on in the city of Los Angeles?”

“What was going on here (the San Fernando Valley) was, for me, a miracle. It sounds simple, but it’s not. They knew that they killed my son, and that he was an honest man. And we had the support of two churches: one was a working-class church from the streets, and the other one was big, the Church on the Way. No-one signed anything, there were no contracts… What was going on here was helped by God.

“And in Los Angeles it wasn’t?”

“The rules were different.”

“And why did the Pacoima Park meetings end?”

“It had already been three years, and to carry on we needed funds. And it was tiring, man. There were no instructors, no jobs to offer the guys, there was nowhere to put the kids so the adults could go to school… And in the middle of all of it was politics, because they were watching everything from prison. They always know more than us on the outside.”

Blinky likes to act things out with his body and voice as he speaks. He doesn’t so much say the last phrase as whisper it. But it’s hard not to believe him. One might consider it possible that part of what he says is not correct, or is imprecise, but it’s hard to imagine him lying, that he doesn’t believe what he’s saying. He speaks with passion, his Spanish inflected with a US accent that mixes identities and jargon. Vatos, madrecita, “commodities.” He leans back in his chair, hands on the back of his head. At 58 years old he’s so bulky that his arms look too short to belong to a boxer. Suddenly he sits up, and continues talking.

“Look, I’m not an idiot. I knew other things were going on, but they didn’t have anything to do with me. My deal was to stop the violence. It’s like a battery: there’s a positive pole and a negative pole. But it makes energy, man! The question was how to stop the violence, how to make it so that mothers in the neighborhood could sleep at night. It was for the barrio, for Latinos. When we started seeing elements outside of us trying to use what we were doing, we stopped holding the meetings, but carried on doing the work. So that’s when we became an NGO.”

“In 1995.”

“It’s complicated, because they’re rejected wherever they go. People call them worthless, say “you guys are criminal dimwits from nowhere”, “and your parents too”… And there’s the economic interest: In this country there are many who want the prisons filled, because they are privately run and charge 55,000 dollars a year to keep someone there. Prisons are on the stock market now. They’ve turned life into a commodity.”

“Aren’t you exaggerating?”

“Look at Columbine. Two boys go onto a campus and boom, boom, boom… When the same thing happens in the barrio, all they say on the news is, “look at those animals”, “those sons of… where are their parents?” And they give you a 25-year-to-life sentence for shooting someone in the arm. And look at Columbine: Those guys planned it, they planned it all out. They went into a school, and they killed people. And on the television they were like, “what happened to them?”, and played some sad music. ‘Why did it happen? What could we have done to avoid it?’ It was the same with that other guy in Arizona who attacked a member of congress. They said, ‘Oh, what did we do wrong?’”

* * *

Ernesto Deras, Satan, has the appearance of someone who takes everything seriously. Even though a little while after the Pacoima Park meetings ended he stopped being the leader of the Fultons, and a year later he “cooled off” and left the Mara Salvatrucha behind, he still walks rigid, almost tense, a hangover from his Belloso battle days, like someone whose life depends on not folding, on showing they’re still strong.

In reality, he is. He welcomes us to a meeting room at the offices of Community in Schools, the NGO that Blinky Rodríguez set up when the truce failed. Ernesto has been working here since 2005. Blinky convinced him again. His job is to assist young people at risk, and intervene when there is violence in the streets, to speak to gang leaders to avoid acts of vengeance, and to stimulate dialogue now that the park meetings aren’t so frequent. And for that you need for people in the barrios to know your name is Satan, and for them to continue having respect for you. His supervisor, until a few months ago, understood that: It was Danilo García, Big D, who died last June of cancer.

Ernesto sits down across the table and says hello. He is polite, but doesn’t soften his gaze. He fixes his eyes on the Dictaphone, which is still off, and he makes it clear to us that he has had bad experiences with journalists in the past. Some have blamed him for war crimes, and others have used his words out of context to justify things that aren’t right. We take note.

“Can you tell me why the agreement in San Fernando Valley didn’t work out?”

“Look, for a year there was a truce, there was dialogue. And for a while, everything worked well. But in 94, bit by bit, Blinky and Dano (Big D) left because they didn’t want to get involved in politics, to put it that way. It wasn’t well thought-of anymore and they pulled back, and the only rules left were the banning of drive-bys and of murdering the mothers of gang members. But most things went back to how they were before. The only thing that was different was that if you wanted to kill someone you had to get out the car and then get them.”

“The drive-by rule was imposed by the eMe. Could the Pacoima Park truce have happened without the eMe’s backing?”

“It’s really hard, really hard. For what happened then to happen… It’s really difficult to do anything like that unless they give authorization, because almost all the gangs respect and fear those people, you know? They can’t do anything unless it’s under their control.”

“Those people”; there it was again, the fear of naming the Mexican Mafia. Again the feeling that in Los Angeles anything to do with gangs is watched, and kept under threat, from the prisons.

“Enesto, why are you scared of the eMe?”

“It’s not that I’m scared of them. It’s more like respect. From the moment you decide you want to be a gang member in the Los Angeles area, you automatically have to be a Sureño, and use the 13. When you do that, you’re accepting the rules. You accept who’s above you.”

“And you accept that they turn the green light on you, like they did with the Mara Salvatrucha in the 90s.”

“In those days, when we saw that there was a green light given against us we powered up and said ‘bring it on’. But when you try to obey rules, you don’t think about the homeboys on the outside, but about the ones who are inside. Let’s say there’s five Mara homeboys in one prison and 200 who are against them, what are you going to do? You have to be on the offensive, for the homeboys inside.”

* * *

By the early 90s the Mexican Mafia were already much more than a prison gang. From their prison cells, with the support of carnales who were free, the organization’s main leaders extorted small-scale drug dealers and were already running their own sales of crack and heroine.

Beyond that, payments to the Sureño gangs were practically everywhere. Each clique and gang paid contributions according to the size and significance of their business. The more that Latino gangs grew and got involved in more serious and lucrative crimes, the more they had to pay, and the more coercive power the eMe had over them. It was a spiral that held Latino gangs in a tighter and tighter grip. When risking a 20-year sentence, it’s much more necessary to have allies in prison than for a petty thief whose only worry is spending a few months behind bars.

Even so, in recent years retired eMe members have admitted that at the start of 1992 the Mexican Mafia wanted to definitively consolidate their control of the streets, and that goal would shape one of their carnales: Peter Ojeda.

In January that year Ojeda, known to all as Sana, summoned all the Sureño gangs from Orange County, in southern Los Angeles, to a meeting in El Salvador park, Santa Ana city. Once they were there, in front of about 200 homeboys, he climbed to the top of the baseball pitch stand to rally against drug dealers who were making money on street corners and in county businesses without being sureños. There are recordings of the meeting that show him on that day saying: “This is your neighborhood. You die for your barrio. They should pay a tax for selling drugs in your area.”

Ojeda had just become the first Mexican Mafia leader to order the gangs in his area of influence to extort Mexican drug dealers who were operating in Sureño territory.

Then he spoke in defense of Latino identity in facing Black gangs in southern California. He showed them a written document and announced that from that moment on, drive-bys against members of la raza (Latinos) were prohibited. Whoever broke that rule would be punished the same as a snitch or rapist.

Many of the gang leaders present struggled to understand what he, a 49-year-old man with a checkered shirt as grey as his hair, was saying. Ojeda was a veteran gang member, an old member of the F-Troop, the county’s most powerful gang. He’d come through legendary prisons like San Quentin, Folsom, and Pelican Bay, and now he was back on the streets controlling the drugs business and feeing his own heroin addiction. Everyone knew him, and they knew of his reputation as one of the first and most lethal members of the Mexican Mafia. But what he was saying made no sense. Until that time the eMe were not known for being particularly modest in how they killed people, when the time came.

Over the next months Ojeda continued holding similar meetings, softening up any resistance to his orders from prison, with the eMe’s control. The disturbances that followed the Rodney King verdict, which between lines was a call to arms to Latino gangs against Black gangs, were gasoline on the fire of his message of racial vindication. In August Ojeda managed to gather more than 500 gang members in El Salvador Park.

Other members of the Mexican Mafia began to hold similar meetings in San Diego, San Bernardino, and Los Angeles Counties. On September 18, 1993, the eMe’s friend Ernest Castro, known as Chuco and member of an old gang from east Los Angeles called Varrio Nuevo Estrada, managed to bring together approximately one thousand gang members in Elysian Park, just one block away from local police headquarters. It made news, and the newspapers detailed how organizers checked attendees one by one to confirm they were unarmed, making them lift their shirts so their tattoos could prove that they really were members of a Sureño gang. In public members of the gangs involved said that the agreement to suspend drive-bys was the beginning of a truce.

While gangs felt backed up by the eMe to increase their control over territory through extorting drug dealers, in reality they were entering further and further into the spider’s web of levies charged by the Mexican Mafia.

At the same time, the Los Angeles police insisted on announcing they believed that an apparent call to lower violence on the streets was in fact a strategic move by the eMe to increase control over Sureño gangs, through the imposition of a new set of rules. Beyond that, avoiding drive-bys meant less risk of non-gang affiliated victims during shootouts, and contributed to a lower police presence. Peace is good for drugs sales. Lieutenant Sergio Robleto, head of the Homicide Department for southern Los Angeles, told the Los Angeles Times: “I’m in favor of peace, but in reality what we’re seeing is the beginnings of organized crime.”

The eMe were monopolizing the authority to regulate professional homicide practice. Now, if a gang member wanted to carry out a hit, they would have to park the car. It wasn’t a matter of avoiding deaths, but rather of imposing new rules onto gangs.

Ernesto Deras received an order in 1994 that he passed on to the rest of the Fultons. It was one of the last orders he gave as an active gang member: “The main thing is that the car couldn’t be in movement. You could shoot from a parked car. If you couldn’t get out the car you’d have to do what you had to do and then leave. That avoided many deaths of people not involved with gangs.”

Despite an apparent reduction in gang activity in 1993 in traditionally violent areas such as east Los Angeles or Pico Rivera, statistics confirm that the supposed truce introduced by the Mexican Mafia never fully actualized. In 1993 homicide statistics related to gangs saw a slight reduction in Los Angeles County —724 compared to 803 registered in 1992— but in the following two years they picked up again, reaching 807 murders in 1995. These are in any case slight variations, almost imperceptible in terms of statistics which reflected a general fall in homicides in the area. In 2001 gang-related murders were thought to make up 54.9 percent of total homicides in Los Angeles County.

At the same time, the meetings brought the Mexican Mafia into a new stage in their relationship to Sureño gangs. They consolidated their extorsion business and drugs sales, but in Los Angeles any question about the Mexican Mafia’s dealings is met with a fearful silence. Nobody knows for certain how big the organization is today.

The Trunk and the Branch

We’re sitting in the small living room of a hostel, trying to catch the trickle of internet signal that comes and goes. It is a small backpacker’s place in the middle of Downtown Los Angeles, which seems to have been very meticulously decorated following one single instruction: anything gaudy and exceedingly ugly is in. The floor lamps are engulfed by plastic flowers and the chairs are shaped like enormous hands holding onto the visitor’s backside.

The hostel is poised between central Los Angeles’ past and future: a few blocks east is the bustle of Latino market stalls stacked high with trinkets, and the cluster of trucks selling hot dogs and street tacos, the homeless people who sleep on the sidewalk till noon, and the gatherings of young men in cholo-style clothing on street corners. A few blocks west, buildings are being remodeled by investors, adapted to the demanding tastes of a new generation of professional class; there are high-fashion nightclubs where blond women in expensive shoes form long queues for a table. Central Los Angeles is transforming and characters from both worlds mix every day around the kitsch little hostel in which we are now attempting a Skype call.

Over the past few days we’ve had multiple meetings with Ricardo Montano, known as Hipster, a Mara Salvatrucha gang leader in Los Angeles who we met almost by coincidence. He appears keen for us to note that the Californian Mara Salvatrucha do not look kindly on what their Salvadoran counterparts are doing “down there”. He claims that few homies enjoy as much respect as he does in Los Angeles, and has no problem with us recording his rants against the direction that leaders in El Salvador are taking the gang.

And it’s not just that. Hipster has promised to introduce us to leaders of other cliques who are interested in giving us their opinion about the recent truce established in El Salvador between MS-13 and 18th Street. We’re calling him to agree on a place and time.

When we finally manage to connect, Hipster sounds different. This morning he received a call from the Ciudad Barrios prison, central headquarters of the MS-13 in El Salvador, to warn him about El Faro. The friendly, chatty guy who we had been talking to a few days prior has disappeared. Now, his tone is threatening. It’s clear from the beginning that there won’t be any meetings with the homeboys.

“Look, the thing is you guys didn’t tell me that you had a problem with those guys down there. I did you the favor of talking to you and I don’t want any problems because of it.”

“Okay, Ricardo. What did they tell you?”

“I didn’t even tell the guy what newspaper you were from. I just said I was going to speak to some journalists from El Salvador and he said they must be from El Faro, and that you’d got the guys down there shaken up, you were talking some shit… I don’t really know what’s going on. But let me tell you one thing: I know you guys live there and I’m here, but if you get me mixed up in anything I can do things down there, too.”

We just found out two things: the Mara Salvatrucha’s upper echelons in Ciudad Barrios have let their troops know that we have them shaken up, turned against them, angry, pissed off; and that this guy doesn’t mess around with his threats. We arranged to meet with him to patch things up face to face.

We meet him a few hours later in the parking lot of a Burger King. He greets us with a half-hug and asks us to follow us by car to a Salvadoran restaurant he knows. We get back into our rented Mazda. As we drive it becomes clear to us that this restaurant is in territory controlled by Hipster’s clique.

He turns into a narrow alley that leads to the back door of an establishment. We park next to him and we go inside. At this point, our imaginations run wild and each of us is secretly convinced we’ve fallen into a trap – and this was the desired effect.

There is no ambush waiting for us in the restaurant, and Hipster doubles with laughter at our frightened expressions. “You thought I was setting you up, hahaha… Nah, man. If I wanted to do something to you I would have done it already,” he says, still laughing.

In the end it’s easier than expected to fix things: While two days ago he explicitly asked us to cite him by name, alias, and clique, because he’s a homeboy who’s high-up and needs no permission to say anything, now he asks for discretion, making us promise to change his name and nickname, and not to mention his clique. That’s why Ricardo Montano is a fictitious name.

* * *

The relationship between gang members from California and El Salvador has gone through profound changes since the first Mara Salvatrucha and 18th Street homeboys were deported to Central America in the late 80s and 90s. The first arrivals had Los Angeles on their mind constantly. Despite the geographical distance, they established gang cliques while trying to respect the ties of hierarchy and the rules from “over there”.

Then, other generations came along and both gangs entered a phase of virulent expansion. It’s no surprise that most deportees belonged to gangs who had broken with Chicano racism and opened their doors to Guatemalans, Salvadorans, and Hondurans. The deportees emanated a charisma and lifestyle that quickly attracted hundreds of young people who joined the two groups en masse, becoming the majority. Members of other gangs such as White Fence or Playboys were also deported to the region, but they were almost invisible amid the rapid growth of MS-13 and the 18. While Los Angeles was home to a wide variety of gangs, Central American was divided into two poles.

In 1993 Mara Salvatrucha cliques from around El Salvador, conscious of their growth, came together to make important decisions in a kind of general assembly that took place in the “Devil’s Door” park. That meeting would come to alter the history of the Mara in Central America and, in the long term, in the United States as well.

Until that point, each time a homeboy established a clique in, for example, Sonsonate, he would name it after his clique in Los Angeles, which is the reason that even today many young men from Sonsonate consider themselves Normandie or Hollywood. In that meeting the naming of cliques with local names was authorized, leading to the establishment of groups like the Teclas Locos Salvatruchos, from Santa Tecla, or the Iberia Locos Salvatruchos, from Iberia neighborhood of Soyapango. It was the first gesture of Salvadoran autonomy, but it also brought conflict.

In the following years, when young men who had already been initiated into the Mara in El Salvador migrated to the United States, and sought refuge in the gang, the Mara from Los Angeles would explain to them that there was no branch of, for example, the Teclas Locos in Los Angeles, and that they would have to be submitted to the initiatory beating in order to join one of theirs. Likewise, if anyone in their new clique had the same gang nickname as them, the new arrival would have to look for a new one. Someone who came to Los Angeles as Shadow from the Teclas Locas could end up known as Goofy from Leeward.

In return, gang members in El Salvador also began to lose respect for the deportees arriving. They would arrive to a clique all arrogant, demanding a position of authority as a Californian, but the locals would explain that things didn’t work like that, and they would force them to submit to the rules and hierarchies of El Salvador.

Hipster lived on the frontlines of that 90s conflict. Despite having been born in El Salvador, and living undocumented for 20 years in Los Angeles, he considers himself Californian. For the gang members of his birth country, he reserves a careless “those guys over there”, or “those locos from down there”, or simply “the Salvadorans”.

“There are lots of guys who were deported to El Salvador and the guys there killed them.”

“Because they showed up thinking they were all that?”

“Yeah, man. Around ‘98, ‘99 and 2000 it caused a mini war among us, because we also killed people who came here from El Salvador. And a lot of the time they were good soldiers who wanted to contribute something.”

“So there were people who came from Los Angeles and found themselves in trouble here without knowing why?”

“Sometimes they would come to a clique wanting to join, and just because of where they came from we were supposed to welcome them… They weren’t going to kill them straightaway, but they would tell them to get lost, or wouldn’t welcome them into the clique just because they were from there. Any civilian from over there would be more welcome, all clueless and scared, ignorant, one of our countrymen, more so than someone who was already a member, because of what was happening. That doesn’t happen anymore.”

“And how did this mini war die down?”

“These things get talked through. Like, when someone can see something’s harming us, at the end of the day we’re homeboys. It’s not hard to reach an agreement between us. There’s always someone you can talk to.”

* * *

We met Hipster in the middle of a packed Salvadoran restaurant, right on the day that the Honduran soccer team beat El Salvador for the hundredth time in a nail-biting match. At least, it was a nail-biter for the Salvadoran fans who filled the place.

In the city of Los Angeles, liter-bottles of Regia or Pílsener beer, or pupusas with cheese and loroco flowers, or seafood cocktails, had stopped stirring nostalgia by way of scarcity for some time — since before the Free Trade Agreement between the United States and El Salvador came into effect in 2004.

That afternoon the waitresses, too few for the number of customers, hurried around with loaded trays of Salvadoran beers and fresh pupusas, attracting catcalls and leers. In one corner, eyes fixed to the television monitor, Ricardo Montano sat yelling coaching advice and swearing at the defense.

He stood right next to the restaurant’s only empty table, as if to watch over it. He saw our look of ravenous hunger, and invited us to sit. We were unaware at the time, but Ricardo Montano was not there to watch the game. He was working. The three of us sat down and waded into a soccer debate that, as far as we were concerned, was highly technical. Two tables away the only Honduran in the restaurant took the occasion of an error by the Salvadoran back line to make a light joke, which brought the room to an enormous silence until someone decided to speak:

“Look, hijuelagranputa (“you almighty son of a bitch”), the Honduran place is two blocks away, this is a Sal-va-do-ran restaurant. Why don’t you take your bullshit over there?!”

And the whole restaurant exploded into laughter and insults that the Honduran received in good humor. He was known to the place and friends with everyone there. It was the only reason that he left that day with his teeth intact.

The joke broke the ice, and Ricardo ended up telling us how he came to Los Angeles, and how his situation grew more complicated. He explained that aged 13 he got involved with a gang, and in the tone of someone talking nonsense he said that the gang were called Mara Salvatrucha. Before he told us more of his life story, we warned him we were journalists and in the city precisely in search of gang members. His face lit up, and he decided to prove his point: in the midst of the multitude Ricardo Montano lifted his shirt to show us enormous blue letters tattooed on his body: MS. Clients and staff alike looked the other way, and it was then we knew that he wasn’t just any gang member, he was at the very least one confident enough to raise his flag in public. One who knew he was feared.

In journalism you learn that no-one tells you their story just for the sake of it. They tell you their lives because there’s something they want you to know and to say, something they want to be written down. Ricardo Montano wanted us to know that he is an important person for the Mara Salvatrucha in Los Angeles, and he wanted us to say what he thought about how the gang is being run in El Salvador. We agreed to meet with him the next day to talk.

We met in the same place, which without the game appeared empty. We were the only ones in the restaurant and Ricardo Montano, who had already introduced himself asHipster, let us know he would need to pause the interview for a moment so he could tend to a client. He is a drug dealer.

The client had arranged to meet him in the local park. While she was on her way, Hipster showed us the product: a small Ziploc bag with a few small transparent stones inside, like tiny shards of glass. The drug is all the rage in Los Angeles, and some Mexican cartels are beginning to produce it on a large scale. It is much less risky to produce and transport compared to marijuana and cocaine, which are bulkier. The product is called crystal and Hipster took out a small fragment to play with while giving us a lesson on how to use it.

“Look… don’t you think the restaurant manager might get annoyed if you take that out?”

His face changes, an expression as if he is the Pope being questioned on the existence of God.

“And what the fuck are they going to say?! They know full well that they don’t have the right to say anything, and if they open their mouth they know what’s going to happen.”

He left to meet his client and returned waving a wad of cash: “Look, 180 dollars in just a few minutes, hahaha… go on then, ask me stuff.”

* * *

“In Los Angeles the Mara are pretty crazy. They have the same reputation, but here they don’t do the same things as they do in El Salvador. The style of crime isn’t the same here.”

Here in the United States, because of the judicial system, you have to be more cautious. Here people have to be taught to do things. Here you don’t carry out a hit until you’re sure it won’t put anyone at risk because they give out years here like cheap candy. It’s not like there, where there is impunity in 90 percent of cases.

When homeboys from down there come up here, they move too fast, used to carrying out hits without consequences. It’s hard for them to adapt here. I’ve been to El Salvador various times. It’s not that they’re crazier than us, but they have more freedom to operate, to do things, and that gives you confidence -- something you can’t have here. Here there’s a much faster response system, ten times faster than in El Salvador.

Like I was saying, it’s not that they’re crazier, but it’s that there are guys from there who come here with two or three murders behind them, fleeing because they’ve killed people down there. Sometimes they have to be brought under control. There are lots of guys who do jail time as soon as they set foot here, like one guy from the San Cocos clique, and another from Prados de Venecia who are in prison because they were moving too fast when they arrived. The difference between the guys who come here from there is that they come here to support and guys from here go there go wanting to calm things down.

* * *

Hipster is speaking:

We’re on the same wavelength with El Salvador, but the rules are different. For example down there if someone isn’t active, or collaborating with the barrio, they make them pay a fee. Basically they make anyone who isn’t active pay rent.

There are things that we don’t support here, but in El Salvador there are homeboys who do things their way. When we speak to them from over here sometimes they rebel against us and say things like, “Y’all aren’t here, we call the shots here and you call the shots there.” We don’t agree with the way that deported homies get to El Salvador and they’re forced to join in things there when they’ve just been doing jail time here, and they have to satisfy the demands of the guys there… no!

There the rule is that if you use the two letters you’re part of the Mara, so you have to contribute and obey the rules and if you don’t, they kill you. At the moment it’s basically the prison that rules. The guys in prison keep themselves going by getting the guys on the outside to charge rent, and they want a load of money. The guys outside can’t even hold onto ten dollars because if the guy in prison realizes you’ve taken it, they’ll get you.

This is what happens: They threaten you, saying, “You son of a bitch, when you come around here we’ll see you, we’ll be waiting.”

The problem is that if you don’t agree with what they’re doing in El Salvador, there’s not much you can do. They don’t always respect your word, even when you’re a homeboy with a say. There was a case of a homie who was deported to Sonsonate, a hitman with a say. He left prison, they deported him, and the clique there were charging him and his mom rent. She had a little shop —you know how people there often have a shop in their house— so the homie called, all desperate, and said, “What’s up with these motherfuckers? They’re charging my mom rent and they came and threatened me.” We called them from here, and they didn’t want to listen to us… 80 percent of the time there’s respect, but in the other 20 they don’t give a fuck.

In terms of knowing about the barrio, its origins, and its politics, we have more wisdom. But in terms of bravery, courage, and command, that’s what they have much more knowledge of. That’s the difference between the Mara from El Salvador and members of the Mara here in LA. We’ve got crazy people, for sure… but not many with the bravery of the guys there. A few of us who would die for the barrio, like they do there…

I want to make clear that a lot of people who came here in the 80s and 90s, to escape the war in El Salvador, have a different ideology about the MS-13 to the second and third generation, and to the generation today. Today’s generation, in their ignorance, say they love the letters: “I love the bestia , the Mara, the two letters I represent – the M and the S”. But they let themselves be carried away by their emotions, they don’t know their origins, how it all began. You can’t love something if you don’t know what it is, and you can’t die representing something that doesn’t make sense for you. What happens now is people are like, “My cousin and my brother were in the Mara, or my neighborhood is Mara territory so I’m going to join too.” They have different motives. Maybe they want respect, they have no mother or father, they’re poor, alone, they want things to be easier.

We have contact with the leaders in El Salvador. Every clique here has one or two members who have been deported, or in prison in El Salvador, so we hear about things through them. Now, those guys aren’t obliged to tell us anything about what they want to do in El Salvador, and we’re not obliged to tell them anything about what we want to do in LA. But they have to understand one thing: We are the trunk and they’re the branch. They know that. It started in LA, it was created here. They don’t like it, but we’re the trunk and they’re the branch.

Something Is Changing in the Mara…

This year, the PNC intelligence shared an illustrated chart with El Faro, detailing the Mara Salvatrucha’s hierarchical structure in El Salvador. It is a PowerPoint slide titled, “The National Leadership of the MS-13 Gang”, with 45 faces of people who, according to the police, are the crème de la crème of the country’s gangs. At the top of the structure are Borromeo Henríquez Solórzano, alias Diablito, from the Hollywood Locos clique, and Ricardo Adalberto Díaz, La Rata, from the Leeward Locos clique. They are presented as the “national leaders”.

Both Diablito and La Rata joined the gang in Los Angeles as teenagers. In fact, La Rata is still remembered on the Angelino streets as Little Rata, a nickname he inherited from his older brother who was shot five times and killed during the gang wars of the 90s.

On one side of these two faces the police have put a small box, the only one without a photograph. Over the box with no face in they wrote: “international leader”, and below: “nickname: Comandari”.

The diagram reflects the old belief within Central American security organisms that the Mara Salvatrucha is a structure with strict hierarchies and a kind of mafia boss at the top who is able to lead, and make the structure cohesive.

It turns out that Comandari is not a nickname, but the surname of a Salvadoran called Nelson Comandari, who Mara Salvatrucha turned the green light on years ago. Instead of obeying him, MS-13 want to kill him.

Nelson Comandari appeared on the California streets at the beginning of this century. He was a businessman —of the illicit sort— who needed street corners and feet to move his goods. He began a strictly commercial relationship with the Mara; he had the product, and the homeboys the street corners. But the possibility of moving cocaine wasn’t the only thing that made Comandari attractive to the Mara. According to various gang members and researchers, who requested not to be identified, Comandari also offered MS-13 a valuable connection: his father-in-law was El Perico, one of the Señores of the Mexican Mafia.

As Salvadorans, the Mara had never received attention for their members from eMe insiders. Aspiring carnales are required to have at least one drop of Mexican blood. While the Mexican Mafia’s hallways of power were off-limits to the Mara, their enemies in 18th Street had members who for years had boasted the title of carnal. Comandari’s direct link with El Perico was, till then, the closest the MS had been to the highest heights of the California gang world.

Interested in his family ties, MS-13 leaders did not just make Comandari a member of the gang, but quickly gave him the keys to the barrio by putting him in charge of the Los Angeles County area – leader of leaders, his status higher than any clique leader around the county.

But this marriage of convenience lasted about eight months. Comandari’s benefactor, El Perico, died of a heroin overdose in prison, and without him Comandari lost influence. On top of that, his growing visibility made him a target for the authorities. Once arrested he immediately accepted becoming an FBI informant, giving away various people linked to the Mexican Mafia. He was brought into the Protected Custody program, whose letters PC germinated the scornful term peceta, used by all gangs to refer to their deserters.

Since then the green light has been given against him, and the United States government has kept his whereabouts a secret.

Although this happened in 2003, his legend continues to prompt photoless boxes in the organizational charts for the gang leaders elaborated by the Salvadoran police.

* * *

On April 13 this year, somewhere in Los Angeles, the Mara Salvatrucha called a general meeting for leaders to discuss “what was happening in El Salvador”. California still feels it their right to be kept updated, and for their voice to be listened to. They have reacted with deep offense at having their opinion ignored on such important “matters”. For the avoidance of doubt, these “matters” are the unprecedented truce between MS-13 and 18th Street which has made homicide rates plummet to levels believed impossible just one year prior.

It's hard to know what was said in that meeting. Gang codes mean that anyone who revealed it would be a snitch. Someone who was at the meeting limits themselves to muttering a few words, with scorn: “Things are going to get more serious… In any case, in Los Angeles we have more important things to discuss than what the guys down there are up to.”

In early June the Los Angeles police launched new charges against the Mara Salvatrucha, and various homeboys have given in to the temptation of becoming informants in exchange for judicial protection. No-one trusts anyone else on the streets, phones are banned at meetings, and gang members look at each other with mistrust.

The change has nothing to do with what is being plotted in El Salvador, or anywhere else in Central America. Around eight months ago, in a Hollywood hotel on the sophisticated north side of Los Angeles, a gang member known as Little One, a young man who is just 29 years old with a Mexican mother, was anointed member of the eMe. Despite the homeboys on the Angelino streets who doubt the title’s reliability, fearing that someone in the prisons is looking to trick the gang, others celebrate the fact that Little One is the first member of Mara Salvatrucha to join the Mexican Mafia.

This piece, translated by Ali Sargent, is chapter two of El Faro’s 2012 special, “The Journey of the Mara Salvatrucha.” Read chapter one, “How Los Angeles Taught the Mara Salvatrucha to Hate.”