This second chapter on the split of MS-13 and 18th Street in Guatemala was published by El Faro in Spanish in November 2012. Read chapter one in English here.

Abuelo is retired now. He took so many turns around the 18th Street gang merry-go-round that he finally grew sick of it. He was once a kid enchanted by Dickies and Van Davis jeans —the big, baggy ones— and Nike Cortez sneakers; he had been a sicario on a bicycle, a voice of authority; an infamous prisoner; he was profiled by the police as a “leader” of the gang... and he grew tired of it. He grew tired of the disorder, the lack of rules, the new kids despising the old code, of their devotion to the trigger. At least, that’s how he tells it.

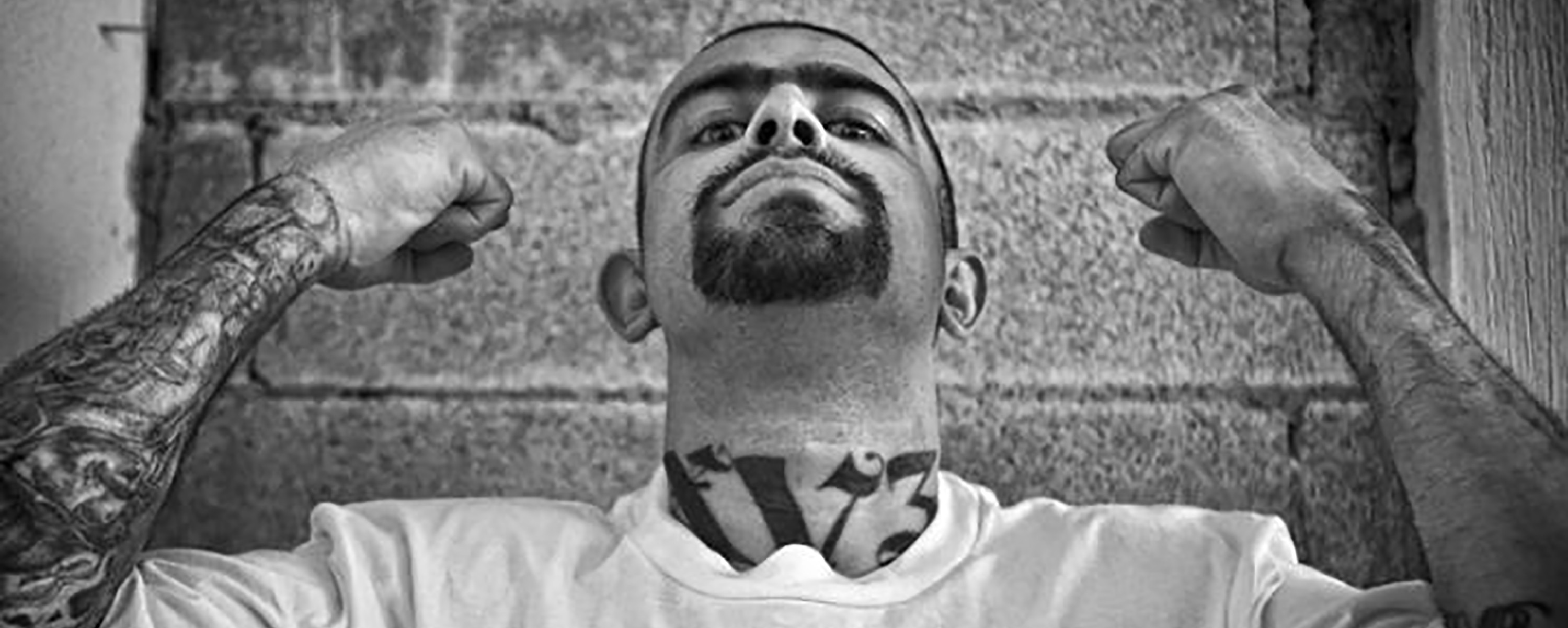

The years Abuelo —“Grandpa”— spent in the gang were enough to cover him completely in tattoos: the ink blots out his belly, weaving its way up his chest and along his arms, creeping up his neck and face and eventually consuming the tip of his nose. His years in the gang left him serving a 50-year sentence in a maximum-security prison, with enough of a reputation that the authorities don’t believe a word he says. They don’t believe that he’s a ladeado, or a traitor to the gang, they don’t believe that he wants to cooperate, and they don’t believe that his newfound willingness to talk isn’t just a plan by the gang designed to confuse them, to fill their heads with lies. But just in case he is in fact telling the truth, the guards keep him isolated from his former homies, and every now and then a police officer comes to the prison to hear him out, and then tells him he doesn’t believe him.

Abuelo enters the interview room at Fraijanes I prison —home to several generations of ruederos, the leaders of 18th Street— with his hands and feet in chains. He is escorted by a swarm of guards, ten at least, all with their faces covered. When they remove his handcuffs, several of the men stand ready with batons in hand. But Abuelo isn’t an intimidating person, even if he has scrawled “Fuck the World” along his forehead in dark ink. Even if the only skin visible on his face is the negative space that forms an enormous “18” across the whole length of it. Even if he’s a murderer. Abuelo has a big, wide smile with uneven teeth, a round face and a pot belly. He looks like a giant baby-faced boy, except that he has “Fuck the World” written on his forehead and the number 18 outlined on his face and he is in prison for homicide.

Abuelo is a veteran of the gang. He watched the Barrio take its first breath in Guatemala, which is why he can tell its story and why his palabra —his word, his authority— has always carried such weight. But to say “gang veteran” in Guatemala is just a figure of speech: Abuelo is 30 years old and has never been to Los Angeles, he doesn’t speak English, and his only knowledge of 18th Street’s original philosophy comes from what he learned from those who were deported to Guatemala from the United States and are no longer here: either because they went into hiding, frightened by the madness they had given birth to, or because they went back to the U.S., or because they were killed.

In neighboring El Salvador, the majority of 18th Street and Mara Salvatrucha leaders are in their forties, and sometimes even their fifties. The most famous and probably most respected among them were jumped into the gang in Los Angeles and boast of having battled with dozens of enemy cliques, of having suffered the scorn of Mexicans and gringos alike, of having lived under the Sureño order imposed by the Mexican Mafia. Some Salvadoran MS-13 members were stoners: the true founders of the Mara Salvatrucha. But in Guatemala, no gang leader is older than 30 and every generation of ranfleros, those who call the final shots, gets younger and younger. In the streets, the gangs are recruiting more and more children who have an increasingly deformed and degraded understanding of the old southern codes; respect for myths and traditions disappeared a long time ago.

One of the main reasons for this generational difference likely has to do with the difference in the years that Salvadorans and Guatemalans migrated. A study conducted by the Central American University (UCA) and the International Network on Migration and Development found that most Salvadorans living in the United States between 2005 and 2007 had entered the country before 1990, while most Guatemalans arrived after the year 2000.

According to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, between 1970 and 1989, 166,846 Salvadorans obtained resident status in the United States, which implies that they pursued a lengthy process of establishing roots in the country. During the same period, only 82,684 Guatemalans obtained this same status — less than half the number of Salvadorans given only the raw numbers, but an even greater disparity when accounting for the fact that the population of Guatemalans living in the U.S. was nearly double that of El Salvador’s.

In short, Guatemalans migrated later and migrated less to the United States than Salvadorans did.

Guatemala’s gangs were always less Angeleno than their Salvadoran counterparts, and even more so after 2005, when they remade the gang’s philosophy and told the old California clecha, or code that had anchored El Sur, to go to hell: the Mara Salvatrucha, because it was this foolish philosophy that had forced them to coexist with their enemies for so many years; 18th Street, because it was precisely that cursed clecha that had left them at the mercy of MS-13’s treachery. To never forget the day of that rupture, Abuelo had it tattooed on his arm: 8/15/2005.

Abuelo was 11 years old and living in the urban slums of Guatemala City’s Zone 6 when he met his first gangsters deported from the United States. He was a member of a breakdance crew called King Master Techno, his street name was Rebel Boy, and his favorite thing to do was dance.

“In 1993, three locos came down from Los Angeles, right. At the time, we had a crew and we were dedicated to dancing,” he recalls.

“Dancing?”

“Yeah, we would just dance. We’d, like, set up outside a high school or someplace, and there’d be girls and everything. That was our thing. There weren’t any problems with fighting, there wasn’t a lot of drugs.”

“And you were just focused on dancing?”

“Yeah, that’s why we would get together, just to dance. We called ourselves the KMT, King Master Techno, like “los Maestros del Baile” (“Dance Masters”), you feel me? Eventually those three came down from the United States and they showed up to the spot where we were always hanging out. They had just been deported. One of them was named Loco, another was called Gerson, and I don’t remember what the other guy’s name was. They were all between 18 and 20 years old. They told us about 18th Street, what shit was like in Los Angeles, and everything else. And we liked what we heard.”

“Do you remember the first time you saw them?”

“Yeah, man, we were always going around with our boombox, hanging out and practicing in parks and shit. That day, we were rehearsing and they just showed up, dressed like they did, all loose and baggy, asking us what we were up to, what we were working on. We told them we were a breakdancing crew, that there was a handful of us from different neighborhoods. So they just showed up and asked if we wanted to hear about what was what was up with the 18. We asked them what that was, and they told us it was a gang up in Los Angeles, that was fighting with other gangs, and that they wanted to expand to other places, that there weren’t any problems or anything, that the problem up there was with other gangs; at the time, the Mara Salvatrucha wasn’t even here yet. There were just some dance gangs in different zones of the city. Because, even at parties and shit, we’d run into people from other zones and...”

“And you’d fight?”

“No. We’d be dancing, and then we’d form a circle and one of us would jump in the middle and one of theirs would jump in, and we’d battle to see who danced better. There weren’t any problems, no one had guns. Like I said, drugs weren’t much of an issue, we were all really healthy. That was where he first told us that we’d have to be baptized, that we had to get jumped into the gang, into the Barrio. We asked him what that meant, what it was like, and he said there would be three guys and you would be alone, and the three of them would try to kick your ass; you could defend yourself, to prove how much of a badass you were. And so we said okay, go ahead, jump us in.”

“How does someone convince you to join a group where you have to let three guys beat the crap out of you to be let in?”

“I mean, we were just kids… what else were we gonna do? How can I put it… It’s like, if we joined, everyone would know our gang, not just here, but in Los Angeles. Everybody dreams about that. Who knows, maybe people would even come down from there or they’d take you up there.”

“Did you have family up there, in the United States?”

“My siblings and my dad.”

“Did everyone in KMT get jumped in?”

“Yeah.”

“How many of you were there?”

“There were about 50 of us.”

The break-dancers from the Quintanal neighborhood in Guatemala City’s Zone 6 would thus become the Hollywood Gangsters clique of 18th Street. According to the authorities and several former and current gang members, it was the first time in Guatemala that a group of young men referred to themselves as a ‘clique’ and self-identified as members of a Sureño gang.

* * *

In the early morning of Wednesday, February 4, 1976, a trembling earth shook the country awake. The earthquake registered 7.5 on the Richter scale, laying waste to the capital at three in the morning and leaving the entire country in ruins that would take more than a decade to rebuild. Between 23,000 and 25,000 Guatemalans died buried under the rubble. More than one million people lost their homes.

And as tends to happen when misfortune strikes —an earthquake, a dictator, a tropical storm— the massive disaster hit the people with the least the hardest, leaving them with nothing. The earthquake devastated the capital, but it also affected the departments of Chiquimula, Chimaltenango, Petén, Izabal and Sacatepéquez. In two months’ time, 126 precarious settlements sprung up on the outskirts of Guatemala City, on the periphery, next to the garbage dumps, along the sheer cliffs of the canyons or on the steep slopes of the ravines. 126 slums, shantytowns, ‘misery villas’...

The earthquake of ’76 destroyed a country already mired in civil war since 1960 — a war that would not end until 1996. After the disaster, the conflict continued to produce its endless trickle of refugees fleeing Guatemala’s rural interior in search of survival in the capital. By the end of the 1980s, state security forces were fully dedicated to pursuing the revolutionaries entrenched deep in the mountains, and in their unsparing rage, the army scorched the earth and swept away tens of thousands of Indigenous people who were, once again, dispossessed of their lands.

In a country torn apart by disaster and war, no one gave a second thought to the children of the refugees who filled the city’s invisible spaces, or to the children of those children…

* * *

In 1985, Guatemala was ruled by General Óscar Humberto Mejía Víctores, who had taken the presidency in a coup against another general —Efraín Ríos Montt— who in turn had couped another general who had himself committed electoral fraud.

That year, at the end of August, General Mejía Víctores had a bad idea. Or, at least, an idea he would come to regret: raising the bus fare from 0.10 to 0.15 cents Quetzales. In an already explosive time, the streets erupted in an instant: university students shook the country, labor unions backed the movement by calling for a general strike, teenagers at public high schools joined in, and along with them, the incipient gangs of the 80s.

While Guatemala’s security forces were busy with other matters, gangs were forming in the capital city and they had started fighting each other, committing crimes, defending their respective territories, and, for the most part, calling themselves maras: Mara Five, which operated in Zone 5; Mara 33, which controlled a large part of Zone 6; The Mara of Plaza Vivar, in Zone 1; Mara X, which operated in the neighborhoods of El Milagro and Carolingia, in the neighboring city of Mixco; the Unión de Vagos Asociados (the UVA, roughly, “union of associated vagrants”), which controlled the area around Mixco Park; Los Monjes de Belén (“the Monks of Bethlehem”), in the Belén neighborhood of Mixco....

These were organizations created by teenagers, and some of them, like the Mara 33, boasted several hundred members. They were not necessarily criminal organizations, or at least were not created for that purpose — internal structures were virtually nonexistent, and firearms were rare. Many of the boys associated with these gangs were students at the public high schools closest to what they considered “their” territory: for example, most of the kids with Plaza Vivar were students at the Instituto Central para Varones and Rafael Aqueche schools; those with the Mara 33 attended Enrique Gómez Carrío; and those with the Mara Five went to the Instituto José Matos Pacheco.

The army’s violent reaction to the protest movement provoked a response in kind, and what began as a show of citizen discontent quickly morphed into something more like rioting and vandalism.

Gustavo was a teenager who had been on his own since he was a kid. He ran away from his home in the interior of the country and fled to the capital, where he lived on the streets for several years. In those years, he was a member of the Mara de la Plaza Vivar and attended the Instituto Central, an all-boys secondary school in Guatemala City. He recalls:

“People from the university would come to give their speeches about how we had to fight. Revolutionary speeches. And we were like, ‘Let’s hit the streets and let’s demonstrate... and then the wave we made stopped being just a protest and turned into vandalism. They started looting businesses. We’d stop a bus and take all the money and the people would get off and we’d take the bus wherever we wanted to go, and the country was thrown into chaos, and people from the interior started sending us food to eat at the school. Since I had been on the street, this made me really happy. I was in seventh grade. I lived at the school for about three months, but the other students had families, parents. And their families started bringing them back home. They couldn’t hack being in the resistance, and the movement started losing momentum. So I went and got my homies with Plaza Vivar and they took the place of the students, and the kids from the Plaza came to the school to sleep, eat, and protest, hahahaha!... That’s when things started to escalate.”

Twenty-five buses were burned for trying to implement the new rates and there were days of looting across the city. Students marched on September 3 to the Presidential Palace and in response, General Mejía Víctores sent 500 soldiers and a tank to take control of the university. The Minister of Education decided to cancel school for the rest of the year. Gustavo’s diploma states that he graduated seventh grade “by decree” in 1985. In the end, the government was forced to give in and rescind its decision to raise the bus fare.

“When all of us graduated that year by decree, the gang kept saying we would all go back to school, but we went to the pool halls, to the arcades — we kept going to class, too, but we stopped caring and paying attention. The kids from the Mara Five used to meet up at a place called 21, which was a real pit. So they’d get together, and the kids from the Plaza would go out to a dance, to a famous disco called Music Power, and to another called Three Two One... but these were mobile dance parties, and you’d go to the parties and hook up with girls. From there, famous clubs started popping up in places that were already local spots, like La Montaña Púrpura, where only kids from Plaza Vivar would go. There was another one called Frankenstein, where people from 33rd Street went; the Tivoli, which was the spot for the kids from Zone 5. That’s where they started forming their own groups and fighting over different things.”

When the boys would stay out partying too late, they often spent the night in Zone 1, in the city center, waiting for the public buses to start running again: drinking, flirting, fighting... If you needed somewhere to pass the time until the sun came up, there was one street where you could find everyone and everything, where you were guaranteed to be entertained into the early hours of the morning: 18 Calle. A place that translates, coincidentally, to the same name as the L.A.-born gang 18th Street.

For Gustavo, this nocturnal ritual changed his life: “That’s when all the different groups started coming together in one place, where everyone knew each other... on 18 Calle.”

By 1993, many of the boys had already abandoned their allegiances to the gangs they were brought up with, and now, as members of the expansive and motley 18 Calle, they felt bigger and prouder than ever. That year, Gustavo went to prison for a minor crime, the same year he saw his first two Angeleno gangbangers, in Pavoncito penitentiary. It was the first and last time he would see them.

“The first time I saw cholos was in ’93, when I was already in prison, at Pavoncito. I saw these two locos had come down, one from the Harpies and the other I think was from Pacoima. And these vatos would make signs with their hands, like a language, and I remember one time, a bunch of us were sitting outside the prison’s church, all of us from 18 Calle. We’d just got done sitting through an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting, because they would give everyone cigarettes for listening to that bullshit. We were all just kids at that point. So, we were all just sitting there hanging out, when one of those guys comes over in his white T-shirt and white shoes saying, ‘Hey, where you from, ese?’ and a guy who had spent some time in Los Angeles translated for us. So we told him we were from 18 Calle, and his response was like, ‘Fuck you y su puto barrio,’ and the guy from L.A. told us what they’d said that our barrio was shit, and so all the homies stood up and were like, ‘You’re gonna insult us like that? You don’t even know us!’ And like 50 dudes grabbed those guys and stabbed them to death.”

In the early 1990s, young gang members deported from Los Angeles began arriving to Guatemala, though in much smaller numbers than in El Salvador. Many belonged to gangs that had recently begun to allow members who were not of Mexican descent —gangs like the Harpies, White Fence, or Pacoima— but most of the new arrivals came from one gang in particular, founded in the late 1950s and, beginning in the 1980s, known for its openness to enlisting Central Americans: 18th Street. A short time later, more young men started arriving, lost and disoriented in a Guatemala City they scarcely knew. These latter arrivals were members of a different gang, whose origins were exclusively Salvadoran, but that over the years had come to serve as a refuge for other Central Americans who saw the gang as a way to reclaim their origins without having to masquerade as Chicanos: the Mara Salvatrucha.

The two cholos who were stabbed to death inside Pavoncito prison apparently did not have time to adjust their old L.A. habits to fit their new tropical home. In Los Angeles, where the Sureño gang pact known as El Sur prohibits Latino gang members from killing each other in prison, an offense like the one the two Angeleno inmates committed at Pavoncito would have provoked, at most, a fist fight. But the cholos were also ignorant of something else: the “Calle 18” they were insulting had nothing to do with their mortal enemies 18th Street, in Los Angeles. It was just an unfortunate coincidence of names.

The cholos killed at Pavoncito weren’t the only ones who were confused. In the span of a few years, Guatemala’s prisons had become home to several dozen members of 18th Street, which at that point was the dominant gang by far, overshadowing the rest of the Sureño gangs that had been reduced to a small handful of groups, including MS-13, which had yet to strengthen its ranks in the prisons or on the streets of Guatemala. The 18th Street cholos took it for granted that these Calle 18 kids belonged to a branch of the gang. And this included Gustavo.

“Back then you didn’t hear about the MS in Guatemala, and the 18 was starting to grow, and in the Preventivo, the Zone 18 Pretrial Detention Center, they created a new sector, a big cell to hold the kids from Calle 18, the ones that didn’t have visitors, that didn’t have money, that were poorer. That was where the 18 and the 18 converged, and the cholos started talking about their philosophy, about the clecha and brotherhood, about all the codes of the gang. And no one ever bothered to ask if you’d been jumped in or not, and we started to follow their program. It was more attractive back then. They dressed like rappers, and when you learned that they had a philosophy, that you had to respect a code, that you didn’t answer to personal interests anymore, but to common ones... That changed everything.”

* * *

On May 15, 1998, police were searching for a businessman who had been kidnapped months prior when they finally found him, held captive in a brothel. After rescuing the victim, agents arrested the owner of the brothel. She was later sentenced to 40 years in prison.

The woman had several children whom she had raised alone. After her arrest, each of her kids went their own way, and the youngest was “recommended” to a neighbor’s house. He was a 13-year-old boy named José Daniel Galindo.

As the days passed, José Daniel found himself living the life of a lonely child, deposited in the home of an unfamiliar family in one of the roughest neighborhoods in the capital: the colonia of Carolingia in Mixco, Guatemala City’s western appendage, its poor and marginalized little brother.

So José Daniel went searching the streets for whatever he could find, and one year after his mother’s arrest, he was imprisoned for the first time, in a juvenile correctional facility.

Fifteen years later, few remember that this young man —now 27— was once named José Daniel, and it’s hard to imagine him without a face covered in tattoos. Now, both his gang and the authorities know him only as “Criminal,” and he spends his days locked away in the Fraijanes I maximum security prison. According to a map of the criminal structure published by the Guatemalan police, Criminal is at the top of 18th Street’s leadership hierarchy, along with a few others, like Lobo. On the streets, he’s considered a respected veteran — his reputation brings honor to his taca , his nickname; to his placazo, his tag. He’s part of the gang’s warrior generation, whose great betrayal the 18 still aims to avenge, which perhaps is why his story is stripped of any epic narratives, of a romantic view of the gang. Criminal is young and tough.

In a small office normally reserved for appointments with the prison psychologist, masked guards remove Criminal’s shackles and he sits down to tell his story, his history with the gang. As the minutes pass, the room fills to capacity: the guards don’t want to miss his story, and they squeeze into every corner of the little room, jammed against each other at the front door. Standing behind at least a dozen agents with their faces covered, guards bob and shift their heads, straining to peer between shoulders in hopes of seeing, or at least hearing, Criminal recount something of what remains of José Daniel.

“When my mom went to prison and my brothers took over, I went to stay with a woman we knew, who loved us, then after that it was always to the corner, to where they were; to learn about guns, you feel me? In 1990 there were already some homies, it was already a thing. There weren’t a lot, but you’d see them around, for sure.”

“You were already seeing cliques by 1990?”

“There were already a lot of homies. What you didn’t see back then were face tattoos. Just the clothes and the style, la ropa tumbada, you know. A lot of guys were coming down from California. It’s true what they say, that they came here to expand the Barrio [18th Street]. It’s true that there were crews from Los Angeles who came down, and who came with the goal of building up gangs. And it wasn’t just the Barrio that came here like that; a lot of other Sureño gangs came down too. And then, you know, the MS showed up a little later.”

“So your clique, the Little Psychos Criminal, didn’t start out as a breakdancing crew?”

“No, no! I mean, in my punto, my territory, there were like 22 of us, and of those 22, maybe seven had been breikeros or burgueses — breakdancers or bourgeoisie. A bourgeois is a guy who, like, only thinks about playing Nintendo, riding BMX, skateboarding, that kind of stuff.”

“So, from the very beginning, your crew was dedicated to gangbanging, to crime?”

“Yeah, I guess you could put it like that. We started out like, ‘Hey, if you want to ride with us, then go grab your shotgun and find an MS; if not, get outta here,’ you feel me?”

“So you started out as members of 18th Street from the beginning?”

“Well, I mean, you started seeing it in all the neighborhoods, in all the colonias. Different homies started showing up, some from California, others from here, from Guatemala, who by then, by 1990-something, were already making waves. They’d talk about it like, how do I put it… they’d be like, ‘Hey, there’s a crew over there on that corner, let’s go see what’s up, see if they wanna hear about the Barrio.’ So it was a thing where already we were like, ‘Man! We want to be part of the 18,’ you know. So those same guys would say, ‘All right, then, go ahead, choose which one of you is gonna be the ranflero, the leader, then get to it, you dig.’”

“In the beginning, was money an important part of day-to-day life in the clique?”

“No, no. It was never like that at first, and for years the only thing we thought about like that was feria, some cash for things like, ‘let’s go grab some food.’ Back then, there were a lot of us who worked in maquilas, in factories, in different jobs. But things would come up and we’d be like, ‘Ok, there’s 22 of us so we each have to pitch in 500 quetzales for…’ whatever it was, to buy a gun, stuff like that. But after a while is when some of the crew decided they didn’t want to work anymore, started saying, ‘Nel, ya no, no, I don’t need other people.’ But then something would come up that required money, and so, well, the crew would discuss it among themselves. It wasn’t just like someone wanted to rob or extort on the corner just because he felt like it; but if we all agreed, if we all decided together, well, then it was, ‘Let’s not work anymore, let’s pick up the gun and... let’s go rob buses, let’s go take that corner, let’s go to that store and take everything that guy has.’”

“What year would you say the Barrio started growing in the streets?”

“Already by 2000, 2001. I mean, shit, they were all over Zone 1, in Montserrat… every bus stop you saw was overflowing with cholos. From the Barrio and from the others [MS-13].”

* * *

For decades, the Guatemalan Army was dominated by thuggery and collusion with organized crime, when the military wasn’t directly running the menacing gangs and criminal squads that trafficked, stole, and killed with the protection of the state. When the armed conflict ended, these criminal structures infiltrated every branch of the state security apparatus, especially the National Civil Police (PNC), a process consolidated after Alfonso Portillo assumed the presidency in 2000. Portillo is currently in prison in Guatemala, accused of corruption and awaiting possible extradition to the United States on charges of money laundering. [In 2013, Portillo was extradited to the U.S. where he pled guilty to money laundering. He was released in 2015 and returned to Guatemala.]

Under the following government of Óscar Berger (2004-2008), Carlos Vielman was appointed Minister of Governance —an office that oversees the Vice Ministry of Public Security and the police— and Alejandro Giammattei was named Director General of the Penitentiary System. Both were accused of overseeing a criminal structure dedicated to the execution of prisoners. According to the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG), “this structure engaged in a pattern of continuous criminal activity that included murder, drug trafficking, money laundering, kidnapping, extortion, and drug theft, among other crimes.”

Giammattei, who was later elected president of Guatemala for the 2020-2024 period, was found not guilty in the national courts. The chief of the National Civil Police under the Berger administration, Erwin Sperissen, was also charged for his involvement in several cases of extrajudicial executions between 2004 and 2007 [Sperissen, who is a dual Guatemalan-Swiss citizen, was sentenced to prison in Geneva in 2014 for the massacre of inmates in Pavón]; the head of the Criminal Investigation Division (DINC), Víctor Soto Diéguez, was accused of running an extermination squad; his deputy director, Javier Figueroa, was accused of the same crime and was eventually arrested in Austria, where he had gone into hiding.

In the subsequent period, during the administration of President Álvaro Colom (2008-2012) —whose own Presidential Honor Guard had planted hidden microphones in his office to spy on him— the vice minister of security, Marlene Blanco, who previously served as director of the national police, was arrested and accused of commanding a group involved in extrajudicial killings and “social cleansing.”

This decade of profound institutional decay instilled in the Guatemalan populace a pervasive and justified distrust of their government’s security forces, as well as a widespread and lingering suspicion that the cancer had never died, but was alive and biding its time inside.

For decades, the anti-gang policy of the police was extermination, so no one bothered to ask questions about the origins and nature of these organizations. The period also left other loose ends: the impossibility of determining how many gang members had died as a result of the war set off by the rupture of El Sur , and how many had been victims of paramilitary social cleansing units.

To kill someone, you don’t need to know them very well, and so the years of “social cleansing” also bequeathed ignorance — a profound ignorance, on the part of the state, about MS-13 and 18th Street.

Carlos Menocal, who served as Minister of Governance until January 2012, explains: “When Colom took office [in 2008], the government believed that the Salvatrucha and the 18 were like a single gang, and they didn’t understand the meaning of ‘cliques.’ They also thought that the 18 and the MS had their capo, their one big boss, and that everyone else was just a soldier.”

Juan Pablo Ríos is head of the PNC’s homicide task force, and knows more about Guatemala’s gangs than perhaps anyone else in the agency. He is part of a new generation of young officers who managed to climb the ranks quickly, following a long period of obscurantism that characterized the country’s security forces for decades.

Ríos’ team is responsible for putting together the pieces of an incomplete puzzle. He coordinates a working group that is subdivided into two specialized units: one to investigate 18th Street, the other focused on the Mara Salvatrucha. He meets nearly every week with the President, Otto Pérez Molina, together with Minister of Governance Mauricio López Bonilla.

Since taking office in January 2012, Ríos and his team have worked to demystify the two barrios, learning to differentiate between the two and to understand the impact that the rupture of El Sur has had on these twin gangs intent on fighting each other to the death. The Mara Salvatrucha, they found, had maintained the stealth and cold-blooded instincts that had helped them secretly plot their betrayal over years, in silence, crouched down, calculating and patient. 18th Street, meanwhile, still had that dagger stuck in their back, still held in their hearts the shame of having trusted an enemy. It was the anger of the humiliated, the hostility of the betrayed who wait to exact their revenge. This new generation of dieciocheros is a loud one, constantly competing to see who can thump their chest the hardest.

For years, Ricardo Guzmán was the chief homicide prosecutor in the country. His assessment of 18th Street echoes that of Ríos: “The 18 have become more disorderly, more bloodthirsty, in the sense of attacking citizens. Once, in order to kill a bus driver, they killed all the passengers too; when MS-13 wants to kill someone, they aim only at their target. The Mara has businesses, they’re better at knowing how to manage money, and their members are older.”

After 2005, two 18th Street cliques stood out among the rest for being bigger, more bloodthirsty, and bringing in more money: the Little Psychos Criminals and the Solo Raperos, who imposed their voice and temperament on the rest of the gang. Today in Guatemala, the name 18th Street is signed in the handwriting of these two cells and their hardened leaders: Criminal and Lobo. And neither man cares to hide or temper the unbridled violence of his soldiers.

Aldo Dupié, also known as “Lobo,” gesticulates with anger at the mere mention of the Mara Salvatrucha. In his presence, one must only refer to his enemies as “las letras” or “los otros” — “the letters” or “the others.” He is serving sentences for several murder convictions and at 28 years old has managed to become the gang’s most revered leader, from his cell in Fraijanes I maximum security prison. “They had their chance to kill us off and they couldn’t,” he says, referring to “the others” with a hint of resignation, but he immediately lifts his head high and adds: “Here we are, still waging war against them!”

“If they gave us an income, do you think I’d still extort? But if the homies are left with nothing, what else can they do? What do they have? A telephone... I already know how to get paid. If we had work, you’d see the number of extorsions go down, and same with the murders of bus drivers, because there was a time when, unfortunately... we even understood that the driver didn’t have anything to do with it, that the one to blame was the owner, because the driver... if one dies, they just put another guy in his place, and that’s it.”

Criminal is even more explicit:

“We always wanted to show that 18th Street was the shit. We’re the ones who thought about blowing it up with the PNC, attacking the cops, which is something the MS would never think about doing. Our plan is basically, ‘Fuck it… come what may.’ Before, just for something like the guards took one of our homies and transferred him to another prison… it’d be, ‘Hey, you, mirá, go find a couple guards and kill them, then we’ll send a message that it was because of the homie they took.’

“The other gang, starting in 2005, they handled things differently, right?”

“Yeah.”

“They didn’t make as much noise.”

“That’s right. I mean, it was only after we started problems with the authorities that they had to learn to handle things differently. I’ll put it this way: a lot of us had the point of view where, basically, we said, “We want everyone to be saying, ‘Those guys, the 18, they’re going around blowing shit up with the PNC, attacking the whole system, the Public Prosecutor’s Office.’ It even got to the point where there were shootings in courtrooms. But they [the MS] saw all this go down and they said to themselves, ‘Let them get into more trouble, while we stick to the rules of the game.’ And that’s what they did.”

“Some people we spoke with told us the MS has started to acquire more resources, generate more income. That they’re making less noise and bringing in more money.”

“They’ve tried to start doing that more, through legal means, yeah, that’s true. I’ll explain it with an example: let’s say between all of us we bring in 100 thousand bricks, and if we feel like getting high, well then, ‘Let’s all get high today, muchá! We’re all happy. Today’s the 18th of the month, right?” But then those guys, they’ll bring in 100 thousand bricks and… nel, nothing, they don’t touch it.... But we’re like, ‘Let’s enjoy it, who cares, if we run out, we’ll just go shoot up their spot and make them give us more,’ you feel me?

The Mara Salvatrucha remains an enigma for the authorities. It moves in the shadows. An investigator specializing in the gang admits that some cliques still only appear to authorities like bumps under a sheet: the police can see that they’re there, but they can’t tell what shape they take. In the case of twelve of these cliques, the government doesn’t even know a single member’s name.

Two facts have given the police reason to suspect that underneath the sheet is a more complex and sophisticated organization: In 2010, when authorities decided to transfer Diabólico —one of the main leaders of MS-13— to maximum-security prison, the gang ordered the dismemberment of four random victims, whose remains were dropped on the front steps of several government institutions, including the Public Prosecutor’s Office. In the same context, the Mara ordered the execution of bus drivers across the city. In one day of bloodshed, a group of mareros used eight different vehicles to avoid being tracked by police, including a BMW. In 2012, Guatemalan police arrested an MS-13 gang member who managed several legal businesses, including a water purification plant, a cable television service company, and a vehicle importer. But authorities have not been able to determine how and to what extent the gang was involved in these business operations, nor what role this particular individual may have played in the criminal structure.

* * *

Abuelo insists that he’s had enough of it all, that everything is different now, that his homies are too ambitious and don’t care about understanding the gang anymore, that they only see it as a springboard to money and power.

“Why did the gang change after 2005?”

“In 2005, we started extorting to arm ourselves and wage war against los batos [MS-13] ... Because it’s really hard for us to get to them in here, on the inside. So the idea was that we’d give ‘em hell in the streets, you feel me? Kill all their soldiers. But then I start hearing that they’re buying legal vehicles, setting up legal businesses, right. Because, like, all that was coming to an end... It’s all over.”

“What’s over?”

“Extorsion has to end eventually. You can’t go on extorting forever. One day, they’ll stop you and then what will you have left?”

“Do you think Lobo is the one responsible for the aggressive clecha that took over the Barrio?”

“Power does many things. There are a lot of people who want to take control of the Barrio. Lobo came here, he was with us, you feel me. He was my comrade, so to speak. We were in different prisons together, and we were always tight, always a team, keeping tabs on things. And there was a time when his clique was falling apart, but they picked themselves back up. The patajos and matones, the young homies and hitmen, they started coming back out to the streets and started making a giant shitshow of everything. And that’s when he seized power, with his people. Everyone knows the more people you have, the more power you have. El Lobo, how can I explain it… That dude is stuck in his own fantasy, okay? He’s not above anyone. His power is in the people he has, and because he’s part of the old guard. But to run an organization like this, in my opinion —and I’m not saying this just because I’m not involved anymore or anything like that— but El Lobo isn’t any good. He’s not gonna lead the Barrio anywhere good. For him it’s all about killing and killing and killing, and sometimes you need to find other ways to get things done, you know.”

“Others have told us that the MS evolved quite differently.”

“Las letras aren’t in the business of following the Barrio anymore. They’re working with drug traffickers and organized crime now. And that’s something the Barrio hasn’t put any effort into recently. They’re protecting their people. Their people are in hiding. I think they even stopped getting tattoos to make business easier. They already beat us, in 2005. They beat the shit out of us, and now the only ones going after them are the Barrio. But the Barrio only uses anzuelos and patojos, rookies and kids who aren’t worth shit, and the top dogs, los meros meros, they’re nowhere to be found, because the top dogsaren’t stupid; they’re putting their minds to use and working. You know what’s happening now? Say I show up —I’m just giving you an example— and I say: “Hey, chequeo, rookie, go kill a shopkeeper, go kill three drivers and someone else at such and such shopping center for me.” And later, everyone’s like, “Alright, homies, the kid did it, he got it done, so let’s jump him in.” And now he’s a homie, just like that.”

“Just like that”

—They don’t turn kids into homies to extort for the Barrio anymore, they do it to make money for themselves, because they’re running out of people, you feel me. So now, if you work for me the deal is like, ‘Hey homie, check it, we’ll charge such and such rent [extorsion] and, since you’re out on the street, you do the killing, and I’ll do my part from here, from inside, and we’ll go in mita mita, half and half.” And here, on the inside, one thousand, two thousand pesos a week ain’t nothing, you know. In other words, the war isn’t with those vatos anymore, you feel me. Now the war’s with the business owners. Just look at the news and you’ll see who the majority of the victims are: bus drivers, store owners, some business owner or another… You don’t see vatos like that anymore, all inked up with letters and numbers. Now everything’s about business.

* * *

In recent weeks, it has been relatively easy for El Faro to establish contact and speak with 18th Street members in Guatemala, in the streets and especially in prison. But the Mara Salvatrucha have proven more elusive. Thus far, we have only been able to contact retired MS-13 members, all of them more or less removed from the present-day reality of this reclusive gang. But today, we were informed that clique leaders from one of the most notorious areas of Guatemala City have agreed to speak with us. Social workers from a local NGO served as our go-between, and have agreed to escort us here on the condition that we don’t mention the organization’s name, nor the name of the neighborhood we’re in, nor the names of the gang members we’re going to meet, nor the name of the clique they belong to.

It’s past three in the afternoon. We get out of our guides’ car on a dull main street and walk with them down a long alley that frays and forks as we make our way downhill. The path narrows, curves, then widens again every ten meters. The walls on either side are lined with doors that open into small two-story homes — so small they barely have facades.

One of the social workers, without moving his head and gesturing only with his eyes, interprets as we make our way through the neighborhood. “The police never come here… A few blocks down the street is where the 18’s territory starts… In this house, they sell drugs.” No doubt, some of these alleys are so narrow and steep that police couldn’t even enter the neighborhood on a motorcycle, and to patrol on foot, forced to walk single file, would be to make themselves sitting ducks for anyone who might want to ambush them. We turn back to catch a glimpse of the alleged drug distribution house, and see a small metal door indistinguishable from the rest of the other small metal doors that line the street. We suddenly have the sensation that with each step we take forward, the narrow passage is closing in behind us, and that left to our own devices we would have no idea how to find our way back.

Accompanied by the curious glances of a handful of neighbors and a few teenagers we pass by, whom we assume are involved with MS-13, we complete our descent until we reach the spot where the gang members should be waiting for us. It’s a cloudy afternoon, but the place, which appears to be some sort of computer lab, has plenty of natural light. We scan the room with our eyes, searching for the mareros. Apparently they haven’t arrived yet, or maybe they’ve already left. From the posters and chalkboards on the walls we can tell classes are held here. In the back, sitting around a table, we see three kids lingering after the last activity. But not a homie in sight.

Our guides invite us over to the table and as we approach, our surprise collides with our dismay. The MS-13 members we are here to interview are, in fact, the three children — one girl and two boys; none look older than twelve. All three are dressed in athletic clothes and are slumped back in their chairs with their arms folded across their chests. On the left is a small, dark-skinned girl with enormous eyes, an upturned nose and a luminous face. She glares at us seriously, marking her territory. In the center, a boy with a round face and slanted eyes hides under a beanie pulled down to his eyebrows, just like Diabólico. The girl is barely five feet tall and the boy doesn’t look much bigger. On the right, the other boy —taller, with a shy face— wears a sleeveless shirt revealing his thin figure. We’ll call them la Niña, El Gorras and El Callado — the Girl, the Hat and the Quiet One.

We start by introducing ourselves and asking their names. We promise not to publish them, but even still, they don’t want to identify themselves. They only tell us their ages: the two shortest are 16, the lanky one is 15. All three are older than they look. Their ages seem enormous compared to their miniscule bodies. When were they initiated, we ask them.

La Niña at 14. El Gorras, the veteran, at 10. El Callado at 12.

The conversation starts out stumbling, tripping over our improvised and somewhat condescending questions, and the misgivings of the young gangsters who still can’t decide whether to be tough and treat us with silence, or to trust us and be themselves.

“Like the boss says, the Mara is for life,” La Niña recites.

“Yeah, from here to the grave, always and forever,” echoes El Gorras.

We had asked them if they liked being part of the Mara Salvatrucha and they respond as if repeating lines memorized from a lesson, as if reciting a pledge of allegiance. It’s also the first time we’ve heard the word “boss” (jefe) come out of the mouth of a gang member. Standard practice among imprisoned leaders we’ve spoken with —the ranfleros, palabreros and llaveros— is to strip themselves of their stripes and shift leadership to the group, to distribute power horizontality, to speak of everyone as equal.

Again and again, their answers fall back on simplifications when we ask them to define the Mara and explain its purpose. “To finish off the dieciocho [18],” El Gorras says without hesitation. “For each of us to have our own territory,” La Niña adds with the tone of a know-it-all. Between the two of them, they explain that two blocks from here, in the street, there is a faucet, and that this faucet is the border between territories. “They can’t come here and we can’t can go there,” La Niña says with a smile. “If we see them coming up, we have to shoot them.”

The girl seems to like this game where she teaches us things about life and death. El Gorras breaks into a boastful laugh when they talk about bullets.

El Callado stays quiet. None of them knows that the Mara Salvatrucha was born in the United States. They don’t know what El Sur was. They don’t know the reason behind the eternal, unending hatred that they’re obligated to honor with bullets. “They don’t talk about those things with us,” La Niña says.

El Gorras explains that he joined the gang because he liked the easy money, because it was nice “to have everything at once, to have everything without working, without making an effort.”

When the girl describes how she imagines a rich and happy life —the life she hopes to realize by joining the Mara— she says: “It’s like every time you ask your dad for a quetzal, he always gives it to you.” One quetzal, cents of a dollar.

The three teenage gangsters live together in a house run by the gang — like a boarding school for little homies; a nursery for assassins. The gang, they explain, provides them with clothing, food, everything they need. La Niña has a mom and dad, and they live nearby, just a few blocks away, and sometimes she goes to see them, especially her mother. She doesn’t get along well with her father, and conveys an unfiltered gesture of contempt when she talks about him, as if he were her enemy. El Gorras has a brother in 18th Street, who lives a few blocks away and guards his side of the border with the gun his bosses gave him.

“Have you ever had a confrontation with him?”

“Yeah, one time.”

“And did you shoot at him?”

“Yeah, and I almost hit him too,” El Gorras says, his face tightening up.

“But he has really bad aim,” La Niña interjects, laughing as children laugh when they make fun of each other. El Callado joins in on the teasing.

El Gorras stiffens his face even more and mumbles something like, “next time I won’t let him get away.”

Thanks to her boss, the palabrero of her clique, La Niña is enrolled in a private school. He signs all the necessary paperwork as though he were her legal guardian, pays all the fees, attends parent-teacher conferences, signs off on her report cards. “Once I did something at school and the principal called my boss and he came and got me and said, ‘What did you do now?’ and I told him, ‘I didn’t do anything…’”

La Niña brags about being a good student: “If you saw my grades, I get all nines and tens.” It seems like the Mara is preparing her for something more than her peers. And El Gorras and El Callado aren’t surprised.

“They own us,” El Gorras says. “We’re like their pets.”

La Niña, an honors student, suffered her first gunshot wound at the age of 11. She has two bullet holes in her body: one in her leg, the other in her shoulder. She shows them off with pride, because it proves how brave and dangerous she is. But she wears a silver dreamcatcher necklace that matches her earrings and the two rings she wears on her left hand, and she still smiles like a child. While one of her friends hides under his hat and the other behind his silence, La Niña seems to be relaxing little by little. She’s wearing her school sports uniform, from the private school paid for by the Mara Salvatrucha.

We ask if they have attacked or killed people. All three say yes, bored with the question as if it doesn’t carry much meaning for them, as if everything involved in killing a person were mundane and obvious.

“Your bosses congratulate you, they give you money, they give you guns. And a gun gives you power. You feel bigger,” explains El Callado, who so far has stayed silent, only nodding along to whatever his companions say, and sometimes not even that.

La Niña nearly leaps out of her seat when the subject of guns comes up. She and El Gorras interrupt each other between jumps and shouts of joy to tell us which ones are their favorites, and La Niña cracks up laughing when she remembers the first time she fired a gun: how her girlish arms couldn’t take the kick of the 9 mm, how the gun hit her in the face and gave her a bloody nose. They talk about how it feels when a rifle’s recoil slams back into your shoulder.

“I like the Mara, I like that people are afraid of you, that people who used to bully you are now afraid of you,” she says.

“I don’t bother anyone who doesn’t bother me, but I will mess with anyone who does,” El Gorras says, with an emphasis on ‘I will,’ on the power to defend yourself that comes with having a gun.

“Well, for me, I like it that people are afraid, that they spread out like little ants and stand aside to let you pass, like you were a colonel in the army or something.”

La Niña and El Gorras are amped up. They’re on center stage now, and finally feel like opening up and talking about everything. The girl speaks with her hands, with her eyes. She’s already forgotten her answers from earlier in the conversation. “Do you ever think about leaving he gang?”

“I do, if I could. I think about starting a family, having children…” La Niña says, suddenly becoming a child, dreaming of a scene from a movie.

“Me too, if that door could ever open, and four or five came out,” El Gorras says.

“Yeah, me too,” echoes El Callado.

“But you can’t say things like that if you’re in the Mara,” El Gorras says.

“You have to keep it a secret,” La Niña agrees. “If you tell your boss you want to leave, Pum!” —she makes a mock pistol with her hand and fires— “He’ll kill you.”

“…”

“Yeah, you get involved in this because your head wasn’t right,” the girl insists.

While the three baby-faced teens talk about heads being in bad places, another boy who looks somewhat older than them walks into the space and sits down at the table, like he knows perfectly well who’s who and what’s going on. He’s extremely thin. He’s wearing distressed jeans and a tank top. His hair is medium length and messy. He looks like he just woke up from a nap that lasted all day. We’ll call him El Despeinado — the one with the messy hair.

“Are you with the Mara as well?” we ask him.

“No, I’m a sicario,” he says. A hitman.

His answer —unexpected, unreal— brings a smile to our faces, which we quickly temper into straight faces when we realize it’s not a joke. He’s not lying. The boy next to us is an assassin. Or at least he used to be, as he later clarifies.

The three young gangsters confirm his story. It’s clear that they all know him. They grew up with him, living in different worlds that collide in the same alleyways. Many gang cliques employ hitmen as part of their business operations. But El Despeinado was a free agent:

“I was a sicario for four years. Not all the time, just when a job would come up.”

“Did you do a lot of jobs?”

“Three. The fourth time I got shot.”

The people who hired him for that fourth and final job neglected to mention that the guy they wanted him to kill was a professional, too, another hitman. And one with more experience than him. El Despeinado didn’t bother to ask too many questions, either. They were going to pay him well, he says. A group from Zone 2 that he had worked for before.

“When I saw him, I went at the guy without thinking, with the gun in my hand. But he saw me coming and shot me first. I thought that was the end.”

And from how he tells it, it almost was. El Despeinado’s chest is covered in scars from the multiple operations that saved his life. His gangster friends make fun of him. They say he looks like a map of the world. Also, his right arm is much thinner than his left, and he keeps his right hand hidden in his pocket. He refuses to show it to us. He says he can move it, that it’s fine, but he won’t take it out of his pocket. He looks dehydrated.

The light is fading and it’s time for us to leave. We make our way back to the main street, this time through different alleys, more winding and even narrower than the ones we arrived through. At times, our shoulders almost touch both walls. El Despeinado and the young gangsters accompany us. They open and close around us in a group as we move through the passages, as if guiding and protecting us. And they probably are, but the scene is an awkward one, given the small stature of two of them and the exceptionally fragile figure of the other.

Back on the main street, we tell them we need a cab and they offer to accompany us a few more blocks until we find one. The group disperses and La Niña and El Gorras move to each of our sides, escorting us. When the others are far enough away and can’t hear, El Callado moves in closer and tells us:

“It’s my job to watch these streets. Especially at night. To make sure the enemy doesn’t come, and to send warning if a stranger arrives. They call me el guardián en las sombras: the guardian in the shadows.”

We can’t find words to respond.

This piece, translated by Max Granger, is chapter two of El Faro’s 2012 special, “Guatemala After El Sur.” Read chapter one, “The Day MS-13 Betrayed the Guatemalan Sur.”