In the last year and a half, a wave of homicides spurred by drug trafficking has brought Costa Rica to the international headlines that for years seemed reserved for northern Central America. The 907 homicides registered in 2023 in a country of 5.1 million, a 37 percent increase in one year, pushed violence for the first time onto the list of Costa Ricans’ chief concerns. But it is perhaps even more interesting, as a clue to understand the crisis, that in a poll last year the population said their greatest fear was “losing the country.”

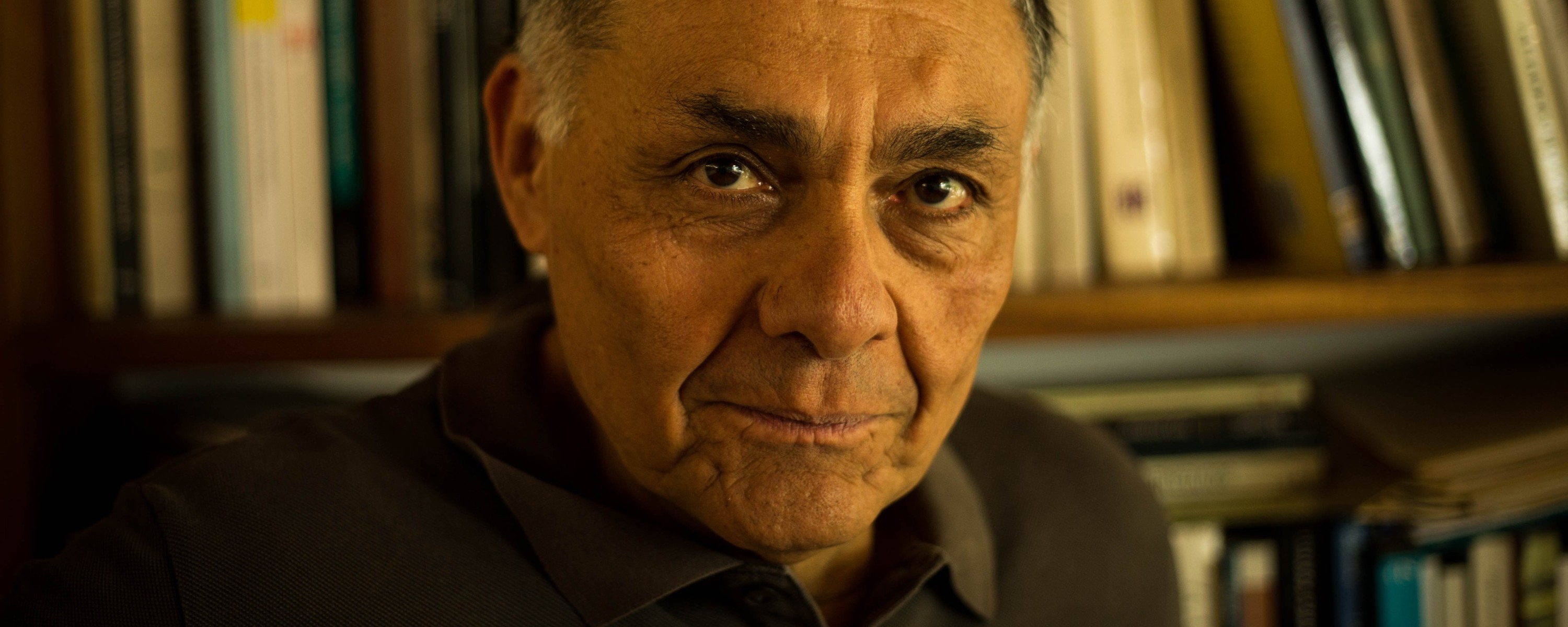

The sensation of collapse extends beyond public security to education, health, and politics, explains Costa Rican historian Víctor Hugo Acuña in this interview with El Faro English. “The bubble of wellbeing burst some time ago,” he laments.

The academic, professor emeritus at the University of Costa Rica (UCR) and a distinguished historian and interpreter of Central America, names the present social crisis among the reasons that half the population supports President Rodrigo Chaves, a conservative with an anti-system discourse who is under prosecutors’ microscope for dozens of cases of possible corruption. “[This government] is not addressing the problem” of violence, says Acuña, adding that Chaves’ calls for extraordinary actions, an echo of the popularity of Nayib Bukele, are mere “saber-rattling.”

“We are at a turning point in the history of Central America,” says Acuña, the cohost of a podcast on the “present and the past” of the region. “El Salvador is a wreck. Honduras, my God. And Nicaragua is scorched earth,” he asserts. “It does the Nicas no favors that the democratic crisis is global. It does help all of Central America that, at this moment, the gringos are trying to be more of a democratizing force, which they have almost never been. But if Trump wins, I don’t know what will happen.”

Struggles for academic freedom and democracy, he adds, go hand-in-hand. Last year the Ortega regime confiscated the archive of the Institute of History of Nicaragua and Central America, which contains tens of thousands of documents of “seminal” worth, says Acuña: “For academia [the fight against authoritarianism] is a question of survival.”

It is said that Costa Rica is facing historic levels of violence. Is that true?

The numbers are there, and they are concerning. But the greater concern among experts I know is not so much its gravity, but rather that this government is not addressing the problem. It is odd: I do not understand why this government does not want to handle it. What is equally unclear is the issue of money laundering. Costa Rica is now a gigantic washing machine. The quantity of new buildings being built all over the place is astounding.

In response to the violence, Chaves called in late January for “extraordinary actions” and said that “the nation must reflect on whether [strong constitutional guarantees] are in the best interest of the population.” In the rest of Central America, this has been a calling card for the suspension of rights, states of exception, and a heavy increase in police presence. In the Costa Rican context, what is extraordinary?

I would say that [Chaves' remarks] are saber-rattling. This gentleman is on the verge of becoming what in the United States they call a lame duck, because he is ending his term and in six months the political horse race will be back, so he is more on his way out than still here. I don’t see him being able to do much, though he must have some echo with the population, because he has about 50 percent approval. People on the street will tell you, ‘Look at what Bukele has done in El Salvador to get rid of all of those hooligans and murderers!’ But here our institutions don’t work that way.

As opposed to El Salvador, Costa Rica obviously does not have an army.

Of course. And a police state in Costa Rica would have to be created from scratch. There are some pockets of elites within the police who are radical, and God knows how the CIA has trained them. But I think that to do something like Bukele has done there must be a tradition, a repressive muscle that does not exist in Costa Rica.

Do the police, the Public Force of Costa Rica, not have certain repressive muscles?

Within the police there are certain people with democratic principles. There is a long road to installing something like a police state. It would require a profound reform of the police, to give them a more militaristic nature, and it would necessarily pass through Parliament and through the Constitutional Chamber. And the next elections are around the corner.

Now, there are always disguised ways to go about it, and perhaps the issue of drug trafficking —of Costa Rica possibly becoming a narco-state— could create an opening for multi-party consensus in the Assembly. But the complaint against Chaves is that he is not doing anything for the Police. He is not reinforcing or supporting it.

Last year it was estimated that two-thirds of the 907 registered homicides were tied to drug trafficking. President Chaves himself has asserted that in Costa Rica “drug trafficking has infiltrated all levels of society.” Is he right?

In terms of infiltration, yes. But how much, I couldn’t say. I’ve spoken with some very close friends in the Judicial Branch, and they say that yes, there must be, just as there is [infiltration] in the Judicial Investigation Organism [of the Supreme Court] and the Police. To say that things here are like Mexico, a state dominated by drug trafficking, is perhaps a bit exaggerated, but we’re headed in that direction, unfortunately.

As opposed to other countries in the region, Costa Rica’s name has never been associated with drug flows. The country presumably has institutions. It is hard to imagine it as a narco-state.

No, that’s no longer the case. Twenty years ago, yes. And maybe from the outside, you in the media continue to feed the vision of Costa Rica as an exception. But here there is a serious problem that is already two decades old. It is already embedded. How much more will the cyst grow? I don’t know. Just like I’m unsure how much it can be controlled.

In a UCR survey last year, Costa Ricans named among their main fears that “narcos will control the neighborhood,” and “making it to old age without a pension.” But their greatest fear was “losing the country.” What country are they referring to?

The Costa Rican myth! Hahaha. Losing Arcadia. I find it very funny, because I’ve heard that expression even from people of intellectual means and from social organizations. It is totally mythical. But yes, undoubtedly, people fear that we are losing the ideal of a country that was certainly always exceptional in the Central and Latin American context. And yes, we are losing it, because of drug trafficking and corrupt politicians.

It was precisely an anti-system wave catalyzed by corruption and disappointment that in 2022 brought Rodrigo Chaves to the fore of national politics.

There have been outsiders in Costa Rican politics at least since the 80s. One of the first was a character —now there are so many like him in Central American politics— named G.W. Villalobos, who tried to be a disruptor. He was a clown for the masses, something of a delinquent. He was one of the first to engage in anti-politics here. Make no mistake: Costa Rican democracy has had its spasms. It has not been linear. It was clear starting in the 90s that the democratic cloth was tearing.

And by the first decade of the twenty-first century, the disintegration of the bipartisan system in Costa Rica was on clear display. Two presidents had been imprisoned and a third, Figueres [Olsen], was on the run. In comes the PAC [Citizen Action Party, founded in 2000] with a moralizing discourse, but after the disappointment left by the two PAC administrations [2014-2022], a little like what happened to the FMLN in El Salvador, public frustration unleashed the Evangelicals. And Chaves emerged from Pandora’s box.

Chaves attacks anyone who questions him. It seems like a drastic and fundamental departure, both in terms of decorum and in his style of governing.

Absolutely. Chaves’ behavior is incomprehensible, because every day he makes a new enemy. We’re not going to search for a psychiatric explanation, but his politics generate no consensus, only conflict. This late into the game, he seems incapable of developing any project or making a concrete change. It’s not only a question of divisiveness, but of respect for institutionality.

In El Salvador, Nicaragua, and until recently Guatemala, the Executive controls the legislature and judiciary. In Costa Rica the courts have curbed some of Chaves’ actions.

Those people from the Judicial Branch have done a great job. Parliament, too. Chaves has very few legislators, and his main political operative, [former journalist] Pilar Cisneros, is another conflict-seeker. I don’t know if they are testing the waters, but they speak poorly about the Supreme Electoral Tribunal and say they want to reestablish the Army. And in Costa Rica you can’t do that overnight. People can’t see that happening. They wouldn’t want it.

Where did the rhetoric about reestablishing the Army come from?

It’s superficial talk. People forget that there has really been no army here for 100 years. What Figueres [Ferrer] did in 1948 was kill a dead man walking. I was taken aback many years ago, as I was reading documents from the National Archives in the United States, and came across a report from a military attaché, if not an official in Washington, on Central American armies in 1930 or 31. And the fellow said that, de facto, in Costa Rica there was no army. There was only a police force, and a very precarious one at that. Any sudden reconstruction of the Army in Costa Rica would be a whole ordeal. It would mean reforming the Constitution, too.

But the Attorney General’s Office has also insinuated this desire in international forums. What sector of Costa Rica are they speaking to?

To Chaves’ core base, which is around ten or fifteen percent. In Costa Rica the far right has always existed. Figueres dissolved the army but kept the Reserve of the Public Force, paramilitaries prepared to deal with Somoza, his number one enemy, or with any problem from the communists. Now everyone forgets about Costa Rica Libre, a far-right paramilitary group that died out with the fall of the Berlin Wall. The far right must identify with Chaves, but if a plebiscite were held to reestablish the Army, I would be surprised if they won.

What kind of debate has existed throughout history about violence?

The myth of Costa Rica is peace. It is the core insignia of the nation. The idea that violence has overtaken the country has advanced hand-in-hand with social decay. As the doors of social mobility started to close at the end of the 1970s and masses of urban population accumulated in quite precarious conditions, there was a growing discourse on the danger of violence. This other emergency, now tied to drug trafficking, inserted itself in the conversation starting in the twenty-first century. There have always been stubborn knots of delinquency, but people my age will tell you that here we slept with our doors open; we never thought to lock our homes.

Has a bubble of wellbeing burst?

The bubble of wellbeing burst some time ago, because the rates of 20-something percent poverty are about three decades old. Social mobility in Costa Rica is completely blocked. There are two worlds here: one where people go to public school and university, and another private. It was recently revealed that there are some 500,000 young adults [of working age] who have not completed high school. And according to the State of the Nation report, if you do not have a high school diploma you are condemned to poverty. In Costa Rica close to 40 percent of the population now works in the informal economy.

Even so, the rest of Central America envies your education system, Social Security…

Yes, the Social Security system is impressive. But the education system is much more delicate. The university system in Costa Rica is indisputably very strong, but social immobility and ghettoization point to the notion that we are losing the country, because to live well now you must live in a gated community.

Are there more walls, more barbed wire?

Yes. The bars appeared in popular neighborhoods some 30 or 40 years ago, but how long have the gated communities been around? Perhaps 20? I live in one, what an embarrassment… And as the rich Ticos [Costa Ricans] used to say, I leave my doors open, hahaha.

A recent household survey suggested that the poorest quintile of society is now renting their house because they no longer have the means or support to buy one, and that the poorest are living increasingly on the margins.

Totally. If there is something fundamental to the reconstruction of the social fabric in Costa Rica, it would be a coexistent and aggressive housing policy. But no government has taken that into consideration. And the same goes for public education.

That nostalgia for a lost country sounds a bit like Make America Great Again.

That’s true. But it’s comprehensible. Thomas Picketty studied this very well at a global level: the pauperization of the middle classes associated with neoliberalism. Stunning numbers. That is the case of Costa Rica, too. We haven’t spent the past 100 years in misery; there was a real social transformation that started in the 40s, a revolution of the middle classes, and it is a fact that it has run dry.

Nor is Costa Rican democracy in good health. Abstentionism is a key indicator. Today people change political leanings like they change shirts. The structural crisis of our political parties also seems important. Yes, people adhere to democracy, in general terms, but there is much less willingness to vote. It’s not that in two or three years we will have a Bukele-like wave, but there is a desire for an iron fist, because half the population supports Chaves.

Young people are not very interested in politics and probably not democracy, either. There is a certain disaffection that favors authoritarian and drastic solutions, because there is little that the generation between 25 and 40 years of age can expect from the state. I suppose they turn to Social Security in extreme cases but, when they can, pay for a private doctor. And at great sacrifice, they try to put their children in private school. People live in the present, in consumerism, and these are all structural global factors leading to de-politicization.

That said, when push comes to shove, I think we are not yet at the point of calling basic things into question like the right to vote. There are always some movements: a roadblock here and there for neighborhood-level things. People take to the streets to remove the director from a school, or because of water pollution by pineapple companies. But civil society lacks its luster.

The global crisis of dialogue, of understanding, has reached you, too.

It’s the feeling of ineffectiveness. People feel like when they mobilize they receive no echo from the authorities. And in that respect the pandemic might have had an adverse effect, in the sense that we got used to virtual communication. We don’t do face-to-face. And then there is the discourse of hatred on social media, which the Chaves administration specializes in. In that respect they are a great deal like Bukele. They have hundreds of trolls. It is quite impressive.

Is a segment of Costa Rica looking for a Tico version of Bukele, even if they will not find one?

Probably. Those are the stakes here in the coming years, but Chaves has neither a successor nor a party. Who could have received the torch were the Evangelicals, with candidate Fabricio Alvarado, but he seems to have burnt out. That said, a rabbit could be pulled from the hat.

For Central America as a whole, how do you read the current democratic crisis? What solutions can we find in the history of the region?

Costa Rica began accumulating institutionality in 1870 or 80, in spite of dictatorships and authoritarian regimes and a lengthy period of semi-democratic politics replete with trickery but without coups or popular insurrections. Other Central American countries have not gone through that process of accumulation. We’re at a turning point in the history of Central America: Will we finally start to accumulate institutionality?

It does the Nicas no favors that the democratic crisis is global. It does help all of Central America that, at this moment, the gringos are trying to be more of a democratizing force, which they have almost never been. But if Trump wins, I don’t know what will happen.

Can the dynasty in Nicaragua continue? I don’t think so. But there is the chance that it can be prolonged for a long time, and if young people come to power, they will need to re-found the country from the ground up… remake the Police from scratch, remove all the courts, re-found the electoral system… and what do you do with the Army? In El Salvador we will have to see how much damage Bukele does. In Guatemala, Bernardo Arévalo has the support of the Indigenous population and civil society, but if the de facto powers —that dark, shadowy bunch— stop him, it will be a catastrophe.

In terms of democracy, can Bernardo Arévalo set a fresh standard?

Arévalo can from the Executive Branch, and Costa Rican institutions from the Supreme Electoral Tribunal, Parliament, and the Judicial Branch. But the other three countries are a mess. El Salvador is a wreck. Honduras, my God. And Nicaragua is scorched earth.

The Ortega regime has shuttered over two-dozen universities across the country. Among the property it has confiscated are tens of thousands of documents from the Institute of History of Nicaragua and Central America. What is the value of this archive?

It is seminal. The archive of the Institute of Nicaragua and Central America is the archive of Nicaragua, much more so than the National Archive. In the middle of the transfer of the digitized collection to the UCR —some 80 terabytes— the Nicaraguan police arrived, but they managed to send it in extremis to the University of Tulane [in Louisiana]. The UCR signed an agreement with Tulane to receive a copy, but the big problem is the part that is not digitized, which is around 60 percent of the archive.

It is alarming to think what these people can do. Especially Rosario Murillo, who takes herself for an intellectual and is completely crazy. I shudder to think of the damage she can do in terms of depredation. There is the risk that the mass of documents will be destroyed or dispersed by the dictatorship. Right now we are in the process of seeing how we rebuild that fabric of research and study of Nicaragua here in Costa Rica. But the Institute is a huge loss. I spent a whole lifetime there doing research.

Nicaragua shutters universities, in El Salvador Bukele lashes out at Central American University, in Guatemala the public San Carlos University has been coopted for years. Even the Ivy League in the United States is a focal point of political confrontation. Is academia the new political battlefield?

Totally. Authoritarian regimes in Central America have found a very efficient way to simply close universities or harass and deride them. To my understanding, Bukele is moving against the autonomy of the University of El Salvador. In Nicaragua academic freedom has already died, and the National Autonomous University of Nicaragua is a sort of propaganda department for the regime. I belong to four initiatives who have prioritized the fight against authoritarianism in Central America. For academia it is a question of survival.

Here in Costa Rica we are under attack by far-right Christians who call us gender-ideology propagandists. There is a kulturkampf over reproductive rights, a culture war that for now we are losing. All of the conquests for women, or marriage equality, are at risk. Our biggest challenge is how much of an adherence to democracy and human rights we can conquer in the population. That is our challenge. We’re taking a beating but we’re in the fight.