El Faro English shines a light on Central America. Subscribe to our newsletter.

The Pennsylvania assassination attempt against former president and candidate Donald Trump drew quick reactions from Central American leaders across the political spectrum as the region holds its breath for the U.S. election in November.

On Saturday, just three minutes after Guatemalan President Bernardo Arévalo posted an expectedly sober note that “the path of violence is not the path of democracy,” AG Consuelo Porras’ office posted a competing message in a clear attempt to show political closeness to the GOP candidate, personally tagging Trump and Donald Jr., invoking God’s blessing, and stressing “unrestricted respect for the law.”

The message betrayed certain irony; Porras has provided no indication of whether she is investigating alleged plans to kill the social democrat Arévalo that were revealed last August after the Public Prosecutor’s Office itself alerted him. Four days after he was elected, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights issued precautionary measures for Arévalo and VP Karin Herrera citing assassination plots involving “state actors.”

Last year, in an open gesture of support for Porras, Republican figureheads accused the White House and U.S. Embassy officials of “picking sides” in Guatemala as the Biden administration rallied with the OAS Permanent Council, E.U., and Canada to condemn and sanction Porras for her still ongoing attacks on Arévalo’s electoral victory.

In Nicaragua, ruler Daniel Ortega struck an even more jarring chord in condemning “all forms of terror” —since 2018, the regime has kneecapped its opponents with terrorism charges— and, six years into his ban of protest, underscoring “our right [as nations around the world] to congregate, express ourselves, and be part of a democracy.”

Central America is no stranger to political violence. In the throes of the Cold War, military regimes virulently repressed pro-democracy leaders and, in the fifties alone, three presidents were murdered: in 1955, José Ramón Cantera of Panama; in 1956, Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza (his dynastic successor was shot in 1980 in Paraguay, shortly after Ortega took power); and in 1957, Carlos Castillo of Guatemala, who had dealt a CIA-backed coup three years earlier.

The presidents of Panama, Costa Rica, and Honduras sent Trump more institutional messages of solidarity. Honduras’ opposition National Party —which took the presidency after a 2009 military coup and stayed close to successive U.S. administrations— posted a picture of Trump with his fist in the air: “Bullets will never silence ideas nor destroy democratic values!”

Nayib Bukele of El Salvador has shown the most open support for Trump’s bid for a second term and invested hundreds of thousands of dollars in lobbying prominent U.S. conservatives to his cause. He reacted to the shooting with a single word in English, again casting U.S. criticism of his authoritarianism as partisan hypocrisy: “Democracy?”

Traditional right-wing party Arena posted Trump’s fist, while prominent opposition legislator Claudia Ortiz and the sole left-wing party FMLN did not publicly comment.

Political violence is a particularly thorny subject in El Salvador; just prior to inauguration, the Bukele administration baselessly accused a slate of historic FMLN leaders of plotting a bombing, then insinuated in a video with Trump Jr. after his swearing-in that the prosecution of former president Trump is lawfare: “We don’t jail the opposition here.”

On July 4, U.S. Independence Day, he echoed far-right neo-revolutionary discourse: “Congratulations to the people of the United States of America… We are inspired by you, not by the ideals you hold now, but by the ideals you had in 1776.”

Ping-pong politics

“You have to acknowledge the advertising genius and nose for politics of the group in power behind Bukele,” says Óscar Chacón, executive director of Alianza Américas. “The Bukele machinery has discerned that those driving politics in the United States are this ultraconservative sector led by Trump.”

“It’s clear that Bukele favors Trump” in November, adds Michael Paarlberg of Virginia Commonwealth University. Whereas Bukele expressed a personal affinity with Trump as early as 2019, he has bitterly denounced Biden’s Central American sanctions policy as foreign interventionism, including the aggressive State and Treasury Department sanctions placed on top cabinet officials for “multiple-ministry, multi-million dollar corruption” and for Bukele’s covert gang negotiations from 2019 to 2022.

At his second inauguration, Bukele paid more mind to a cluster of U.S. Republicans —including CPAC chairman Matt Schlapp and former Ambassador Ronald Johnson (2019-2021)— than to DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas.

By contrast, Biden officials shifted focus to last year’s electoral process in Guatemala when asked about democracy in Central America, refraining from criticizing Bukele’s unconstitutional reelection and absolute concentration of power as they claim to focus on private diplomacy to secure political objectives like an end to the state of exception and visa restrictions including those already obtained for African and Indian nationals.

“As long as Bukele cooperates on immigration enforcement,” Paarlberg continues, “he can get what he wants from Trump. Frankly, that’s not much different from his current deal with Biden, apart from personal friendliness.”

“Bukele likes his role in movement conservatism. He would use the relationship to bolster his image on the world stage,” he adds.

Bukele is in that ship together with Consuelo Porras, who in June sent a delegate to a Pro-Trump Faith & Freedom conference, and has insisted that the State Department visa sanctions affect her human rights.

Trump envoy Richard Grenell, a possible future secretary of state, traveled to Guatemala days before Arévalo’s inauguration and, according to the Washington Post, promised Porras allies that “heads will roll” in the U.S. Embassy if Trump is reelected.

“In Guatemala the Biden administration has highlighted the valiant efforts they made to ensure that Arévalo took office, and for nothing bad to happen to him, whether violence or otherwise,” says Paarlberg. “They see that as the one bright spot in the region that they can highlight and forget about other troubles. The administration has ping-ponged between the countries [in Central America] that they think they can get the most returns from.”

Republicans like Florida Rep. María Elvira Salazar, chairwoman of the House Western Hemisphere Subcommittee, have appeared similarly selective, focusing criticism of Biden’s Central America policy on Nicaragua and Honduras. In a June 27 hearing, Salazar grilled the State Department on its human rights policy but steered clear of systematic human rights violations under Bukele’s state of exception that were documented by the Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission.

Biden’s former Central America envoy Ricardo Zúñiga noted in Americas Quarterly on Tuesday “the growing radicalization of [Trump’s] followers and potential cabinet members.”

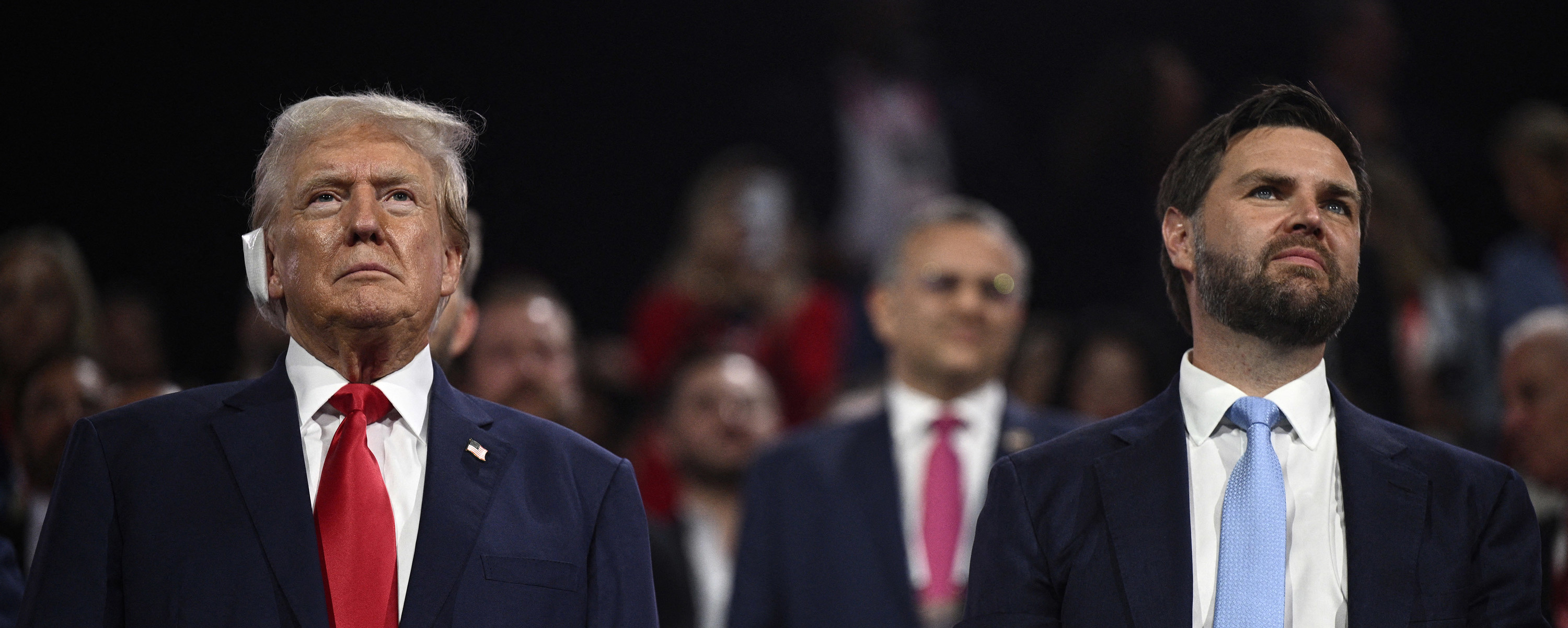

Newly announced running mate J.D. Vance has voiced support for deploying the U.S. military against drug cartels, suggested that migrants are crossing the Mexican border in order to vote in November, and blamed migrants for the U.S. fentanyl crisis, even doubling down on Trump’s assertion that migrants are “poisoning the blood of this country.”

Zúñiga wrote: “The direct effects [of another Trump term] would be substantial, especially for Central America, which would have to suddenly absorb hundreds of thousands of deportees and the subsequent loss of billions of dollars in remittances.”

Salvadoran spotlight

The heightened odds of a Trump victory in November accentuate the political relevance in El Salvador of Florida Rep. Matt Gaetz’s July 8 announcement of a “bipartisan Congressional El Salvador Caucus” with Vicente González, a Texas border-district Democrat.

Gaetz, a rabble-rousing Trump surrogate who attended Bukele’s inauguration and polarized the Republican caucus for leading the removal of Speaker Kevin McCarthy, was explicit: “The purpose of this caucus will be to vindicate the choices that Bukele has made.” El Salvador has shunned the “siren song of globalism,” he added, and “can lead within Central America, and indeed throughout the West.”

“[The new caucus] is more of a P.R. move,” argues California Fullerton academic Ricardo Valencia. “Gaetz is viewed poorly by many Republicans, especially after having removed McCarthy as Speaker. I imagine that they [the Bukele administration] calculate that Trump will win, so that relationship is more important than the [GOP] mainstream.”

“Gaetz is popular with the base. He has very little power in terms of legislation, but has an outsized media presence, and that is of value to a publicist like Bukele,” says Paarlberg. As for González, “he is one of these Democrats who care about border security. I imagine he believes what Bukele says, in terms of being responsible for lower flows of Salvadoran migration. I think he believes Bukele is a partner we can work with.”

“They needed a Democrat [to join the caucus] but couldn’t get someone like Norma Torres,” he adds, referring to the Guatemalan-American congresswoman who has been sharply critical of Bukele as chair of the Central America Caucus, launched in 2021 as Democrats pushed for a democracy and human-rights focus against the grain of Washington’s perpetual migration-centrism.

It was to little avail, says Chacón. “The Central America Caucus has been practically ignored” by the Biden administration, he asserts. Even so, “we Salvadorans in the U.S. are now the second-largest Latin American immigrant group, so a new caucus on issues important to the Salvadoran-U.S. relationship is not in principle a harmful development.”

Meanwhile, he says, the Biden camp is in the wilderness. “The Democratic Party lost its compass, including with regard to Latin American relations,” asserts Chacón. “Especially in the case of El Salvador, there is a [policy] void that must be filled.”

This article first appeared in the July 17 edition of the El Faro English newsletter. Subscribe here.