At the beginning of the twentieth century, many believed that mining was destined to compete with agriculture as the main source of El Salvador’s national wealth. With the prospect of a coming bonanza, Salvadoran political leaders were willing to offer major concessions to attract foreign investment to exploit the country’s mineral wealth. But the residents of mining areas saw things very differently; they suffered the consequences of contamination and complained of their powerlessness in the face of the U.S. mining companies’ economic and political influence.

Their complaints were entirely justified; the mining investors’ influence was undeniable. Their clout stemmed partly from tangible reality and partly from hopes for the future. In their advertisements, the authorities proclaimed that the export of gold and silver was destined to be a source of national prosperity. A 1912 commercial guide said that “there is no doubt that the soil of the Republic [of El Salvador] is extremely fertile, but…the subsoil is as rich or richer than the soil.” It also estimated that by 1912 the export of minerals had reached 15 percent of total exports. The amount of gold and silver the country sent abroad increased from $183,760 USD in 1901 to $1,116,717 in 1909, a stark upward trend that was expected to continue.

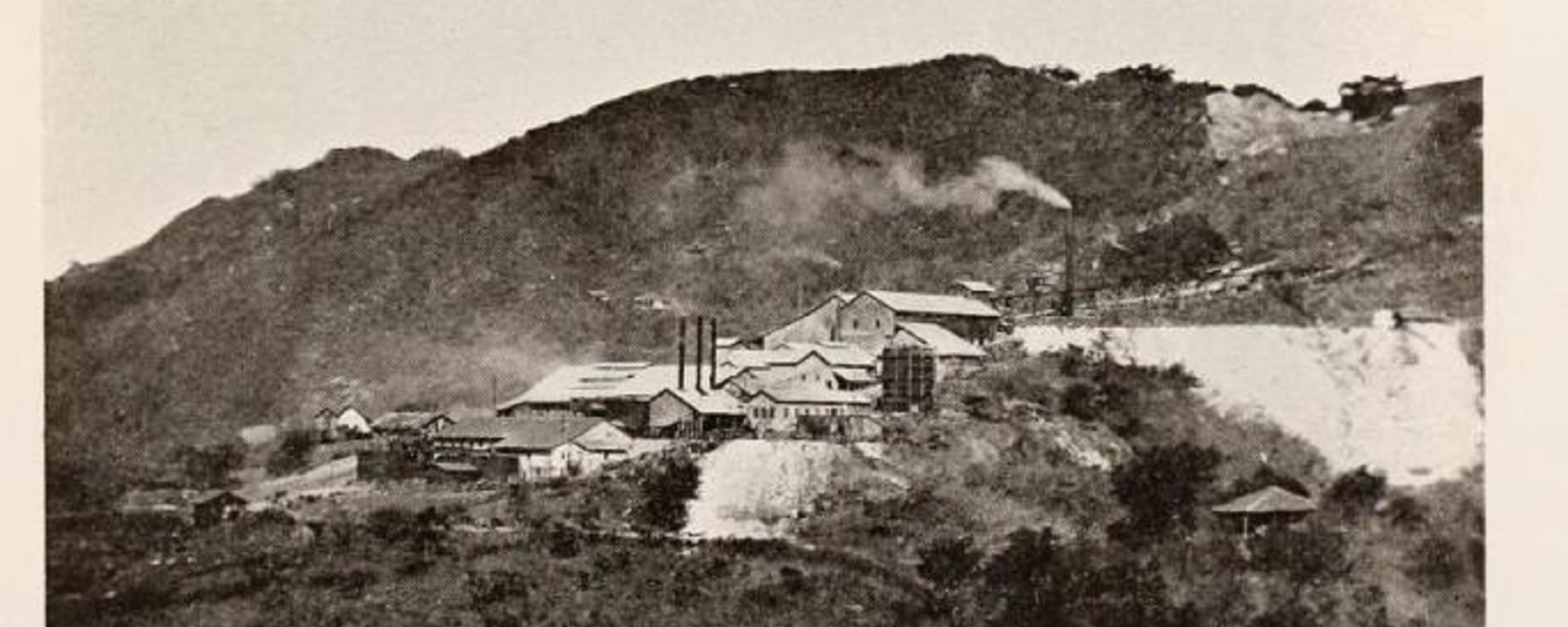

The mine in Santa Rosa de Lima, in the department of La Unión, was a large, modern facility located on land that had previously belonged to former President Santiago González. The mine’s principal owner, Charles Butters, was a Californian engineer and metallurgical innovator who invested heavily in the business. Photos of the Santa Rosa facilities show a vast complex of buildings that dominated the mountainous landscape of the northeastern part of the country. The mine in the Divisadero region, in the department of Morazán, was similar. Harry Percival Garthwaite was the manager of these mines until his death in 1911. Garthwaite was an engineer who had gained experience in South Africa’s mines, which, combined with Butters’ innovations, gave him the knowledge he needed to deploy the most modern mineral extraction methods.

Garthwaite’s economic power and technical knowledge translated into political influence. When he died, his obituary in a San Francisco, California, newspaper described him as the “confidential advisor to the president of El Salvador.” His close relationship with President Fernando Figueroa allowed him to secure the government’s staunch support for mining. The Salvadoran president had such confidence in Garthwaite that when Figueroa wanted to select the official party’s candidate for the next presidential elections (read: name his successor), he sent the mining engineer on a secret mission to Washington to consult with the State Department about which candidate the United States found most acceptable.

To make up for budget deficits, the government sold bonds to Charles Butters' companies in El Salvador (Butters Silver Mines, Butters Divisadero Company, Potosí Mining Company, and San Sebastián Mining Company). In his heyday, Butters felt entitled to visit the U.S. Secretary of State to tell him who should be the next U.S. ambassador to El Salvador.

In the face of such power, it is unsurprising that the authorities in San Salvador allowed gold and silver mining to increase rapidly, despite the pernicious effects on the residents’ health, environmental deterioration, and loss of hundreds of head of cattle. The danger that mining posed was not limited to those damages: the mines were also hazardous places that used large amounts of explosives. In June 1915, for example, the Divisadero dynamite warehouse exploded, causing a fire in which fifty workers died in a single day.

The following is a letter from the residents of Santa Rosa de Lima, the site of Butters’ Salvador Mines facilities, asking Manuel Enrique Araujo’s government for support. The residents, known as Limeños, complained bitterly about previous governments’ indifference to the problems that the cyanide used for mineral extraction created by contaminating the Santa Rosa and Agua Caliente rivers.

* * *

S.P.E. [Supreme Executive Power],

We the undersigned, who are of legal age, this city’s farmers and residents, come before you to most respectfully state our protests: that since General Regalado’s administration, we have been the victims of the cruelest injustice on the part of the mining company, Butter Salvador Mines, which exploits San Sebastián’s minerals, and Tabanco’s Macay Pullinger Company; that through the procedure they use in mines —cyanidation— they have totally ruined this jurisdiction’s only two rivers, the Santa Rosa and Agua Caliente rivers, into which they throw the cyanide that they use in the chemical procedure for extracting gold; that due to the poisoning of the water in these rivers, we, the inhabitants of this unfortunate land, have suffered incalculable losses to our rural properties, to the extent that we have been left nearly destitute, and we will be in total ruin if the beneficent hand of our worthy, honorable, and upright President does not free us from the ignominious and cruel actions of a foreign community that treats us like helots [serfs, in ancient Sparta], mercilessly damaging our properties, which provide our bread and sustenance for our families.

We have raised our humble voice to each of the past administrations to demand justice, in the erroneous belief that our rulers would act as protectors of the weak, but unfortunately that has not been the case, because they, in their path to supreme power, have done nothing more than fill their pockets with gold amassed through the sweat of the brow of their subjects, and have acted as the staunch and unconditional protectors of the strong, of the powerful, because theirs was the kingdom of gold. How could our humble voice against the powerful mining company of San Sebastián resonate with the Regalado, Escalón, and Figueroa regimes, when the mining company exercised unlimited power over them, because of the dazzling brilliance of gold?

But every town has its hour of salvation, and in our town, that hour of grandeur, justice, and prosperity has arrived when the citizen’s rights are recognized. Now, Doctor Araujo and his chosen and select cabinet have ascended to supreme power, and he has demonstrated for all and sundry that his ideal is his country’s greatness, that his predestined crowning glory will be to go down in history and he will be anointed with posterity’s holy oil because he has used an energetic hand to show that the country is not the exclusive patrimony of the powerful, and that there are no longer predatory contracts nor all-powerful foreigners. Encouraged by this intimate conviction that is ingrained in us as well, we do not hesitate to raise our humble voice again to demand justice, asking the Supreme Executive Power to cast its beneficent gaze toward these forgotten places and enact measures to save us and [prevent] the probable ruin that the Mining Company of San Sebastián would cause us by poisoning the water in these rivers, since it will only be greater once the use of cyanide expands as the means through which the company increases the exploitation of its mines.

Herewith, we enclose a list of the injured parties, who share the sentiments of this letter, and the livestock that have been lost; these are but a small sample of the evils caused. We are obliged to prove the aforementioned facts.

S.P.E. [Supreme Executive Power],

The public authority is called upon to put a stop to the harms inflicted on the people; that is why we come to you to demand protection from the Company of San Sebastián, because of the damage it causes to our properties by poisoning the water with cyanide.

Santa Rosa, Department of La Unión, August 8, 1912.

Manuel de Jesús Ventura

Petronilo Vásquez

Matilde Amaya

Rafael Herrera

At the request of Don Víctor Escobar, who does not know how to sign, Manuel de Jesús Ventura

León Melgarez

On behalf of Margarito Menjibar, who does not know how to sign, Roberto Restrepo

Joaquín Escobar

Elías Escobar

Vicente Torrez

Thirty-nine more signatures follow

*Translated by Jessica L. Kirstein

Héctor Lindo is professor of history at Fordham University in New York. This letter can be found in El Salvador at the General Archive of the Nation, Notas Policía 1912. Ministry of Governance. Unclassified box, year 1912, #34-2.