The leaked phone conversations between senior Bukele administration official Carlos Marroquín and a leader of the Mara Salvatrucha, published by El Faro, shed new light on the depths of the deal that the administration of President Nayib Bukele cut in secret with the gangs, and on their collapse. He played Russian roulette with the criminal organizations: He pacted with them, set their leaders free, and later broke the agreement. Others paid the price. Eighty-seven people, most of them with no relation to the gangs, were assassinated in a single weekend.

This whole time, while the president, his ministers, party legislators, and unofficial mouthpieces accused civil society organizations, human rights advocates, and journalists of “defending gangs,” the administration maintained its agreement with the criminal structures. As Marroquín confessed in the conversations, they even freed gang leaders with ongoing criminal sentences in El Salvador and facing U.S. extradition requests. Marroquín personally admitted to freeing Élmer Canales Rivera, alias “Crook de Hollywood,” and transporting him to Guatemala.

The MS-13 members captured in March, in an operation that marked the end of the pact with Bukele, were traveling in a government vehicle and with a government chauffeur.

This new investigation confirms that Marroquín —Bukele’s negotiator with the gangs dating back to 2015, during the president’s term as mayor of San Salvador— informed Bukele, under the pseudonym of “Batman,” of all developments in negotiations with the Mara Salvatrucha-13. It’s hard to imagine that a man like Bukele, who demands unquestioning loyalty, did not sign off on each and every step of the failed negotiations.

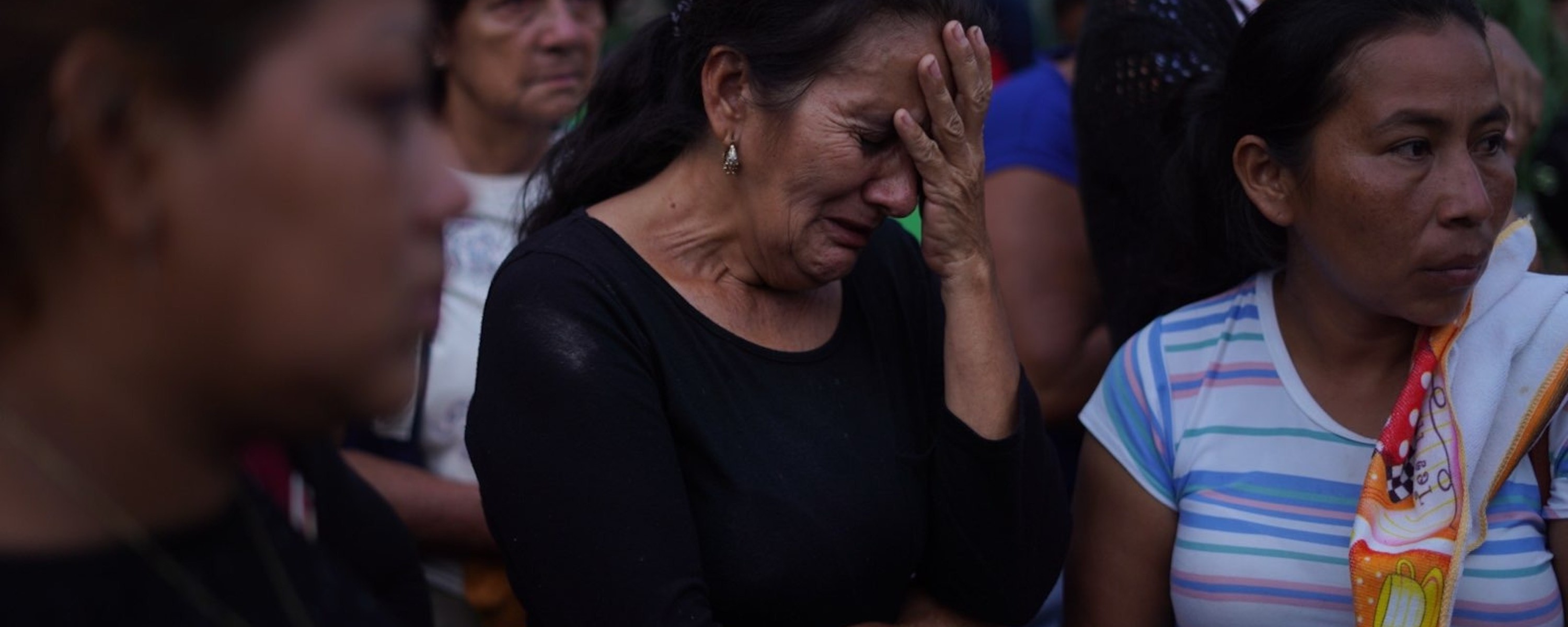

The consequences of his macabre game have yet to fully play out. Pushed by the failure of his security plan, which was nothing more than a criminal pact, Bukele decreed a state of exception and ordered mass detentions. More than 30 thousand people have been detained in almost two months. Are they gang members and criminals? Many of them are, if judging by information provided by the police and prosecutors. But many others are not. Human rights organizations have denounced the detention of innocent people as well as torture. There are political prisoners, among them trade unionists and critics of the government, such as a local radio host who denounced on-air the arbitrary detention of his sister. Reports of government abuse multiply every day, and a dozen people have died in police custody. More deaths to attribute to Bukele.

If, before, low homicide figures provided a veneer of efficiency in public security, now Bukele needs arrest numbers, at any cost, to show off his iron fist. There are obvious similarities between these two phases: absence of the rule of law and customary lying, as the base of a criminal president's political strategy; impunity for officials in his administration; and the wielding of the entire state apparatus in favor of a group in power rather than the public. It’s precisely for these reasons that he needed to prevent anyone from exposing the criminal pact.

In lockstep with the approval of the state of exception, the Legislative Assembly passed a gag order to criminalize publishing information related to gangs. The censorship was legalized just after that pact fell apart and the country mourned 87 dead in the worst killing of the 21st century in El Salvador.

The law warns against the publication of messages or symbols of gang members causing “uneasiness” in the population, an ambiguity sufficient for any judge controlled by the administration to decide what is publishable and what should merit prison time of up to 15 years.

As our investigation of the leaked audio shows, Salvadoran authorities have gone behind the backs of the public to benefit criminal structures. The exposé also explains the assassination of 87 people. The revelations are of public interest, the very substance of journalism. The constitution protects citizens’ right to be informed.

If the attorney general truly wants to pursue crime, he can start with public officials and gang members involved in Bukele's collapsed criminal pact with the gangs. Each of them has blood on their hands. Under rule of law, they would be the ones to face investigation and prosecution. But there is no point in expecting that outcome from a system totally controlled by the president, the figurehead of that criminal pact.