Northwestern Guatemala has been known for years as Sinaloa Cartel associates’ territory, except during the Zetas’ stint in the area from 2008 to 2012 and, more recently, when Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG) began fighting off Sinaloa to take over drug trafficking routes in Chiapas, Mexico.

Inevitably, the fight spilled across the border into Huehuetenango, 130 miles northwest of Guatemala City.

However, in March 2022, the U.S. Treasury revealed that local drug traffickers in this area, named Los Huistas after a province of Huehuetenango, are moving cocaine into Mexico for both CJNG and the Sinaloa Cartel. At first glance, the fact that one local group is trafficking for two Mexican organizations who consider themselves nemeses may seem unnatural in the narco-world.

“I was surprised by the fact that the Huistas could do business with the two most important groups in Mexico and that, despite the fact that they are enemies, they allow the Huistas to supply cocaine to both of them,” says Francisco Jiménez, former Guatemalan minister of governance (2009) and head of the Civil Intelligence Office (Digici) from 2007 to 2008. “It conveys an ability to negotiate, and that [the Mexican traffickers are saying], ‘It’s better not to fight, and sit this one out, because this is an important supplier,’” he concludes.

“It’s a cooperative manner of doing business. It’s no longer a single-group operation, but a cluster of people with similar interests,” Jiménez says.

There’s another explanation rooted in the criminal history of the area. In testimony in Washington, D.C., against Guatemala’s Lorenzana narco-family, Huista member Walter Arelio Montejo Mérida admitted to having sold cocaine from 2000 to 2003 to Antonio Guízar Valencia, leader of the Valencia Clan, also known as “los Cuinis”, active in Chiapas and Michoacan. This latter group, who under the name of the Milenio Cartel was linked to the origins of the Sinaloa Cartel, included Nemesio Oseguera Cervantes (aka “El Mencho”) as an up-and-coming and well-known leader since 1996.

Milenio broke off from the Sinaloa Cartel in 2010. While Montejo was arrested and extradited to the United States in 2012 to face drug trafficking charges in Washington, D.C., Oseguera left the Valencia Clan and formed the CJNG. By 2017, Montejo appeared as “not in custody” of the Federal Bureau of Prisons, meaning he could be on parole, or in custody of another agency.

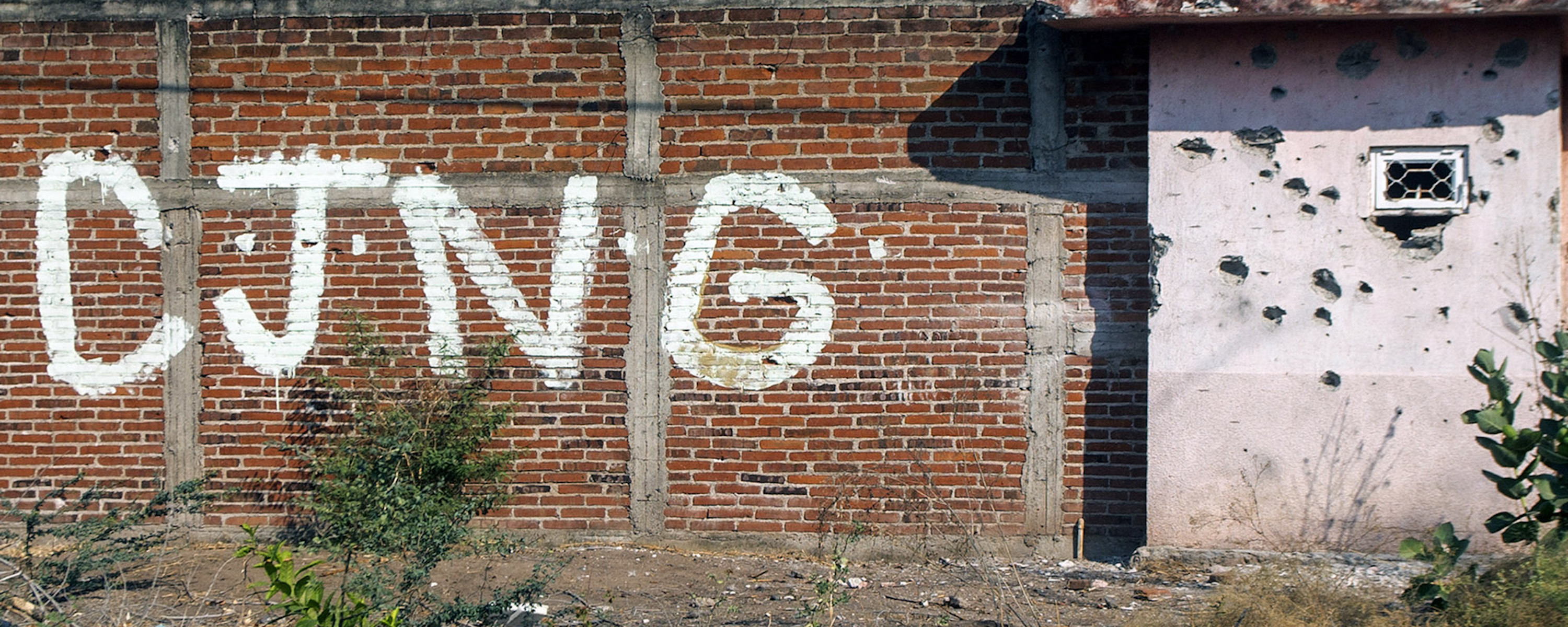

CJNG has been active for years in Mexico, but it came as a surprise that by June 2021 they began showing up in Huehuetenango, where local press reported witness accounts of a heavily armed commando operating a checkpoint and inspecting vehicles on the main road for undocumented migrants and firearms near the town of Nentón, eight miles east of the Mexican border.

At least three press reports in Guatemala and Mexico followed between July and September 2021, detailing heavy exchanges of gunfire that left on the Mexican side a path of SUVs and pickup trucks riddled with assault rifle bullet holes, some set on fire. Any wounded or dead bodies were removed from the scene before authorities arrived. Two of the vehicles left behind had Guatemalan plates.

Colonel Rubén Téllez, spokesperson for the Ministry of Defense in Guatemala, denied to El Faro English any incidents on Guatemalan soil despite the press reports. However, later on it became clear that the commando’s presence was not at odds with the Huistas — a rarity, considering how in November 2008 the Huistas ran off an armed commando of the Zetas and left a path of 17 bodies all the way to the border, at the Agua Zarca village.

A former government official from the area, who requested anonymity for safety reasons, said that the real body count was closer to 60, but that most of the bodies had been carried over to Mexico before the Guatemalan police arrived.

An Old Alliance

It’s unusual for the Huistas not to respond with violence. It suggests an agreement with CJNG, considering that the cartel clearly chose Huehuetenango as an entry point and has recently used Guatemala as a pathway to the Atlantic and to Honduras, which they have reached unscathed. The old link between Mencho’s Valencia Clan and Montejo seems to still be in force.

“Unofficial information reveals that a new and upcoming group in Huehuetenango may have been responsible for the gunfire exchange with Jalisco New Generation along the border,” says the former government official. That would explain the vehicles with Guatemalan license plates left behind on the Mexican side.

“It’s unclear whether they were trying to prove themselves by marking territory,” said the former official, waving his hand, a Guatemalan gesture to indicate insignificance. According to local reporters too cautious to publish stories about it, the Huista hegemony eventually prevailed, and so did the CJNG presence at the border and throughout the province.

One video that surfaced in social media in September 2021 showed four men in a vehicle in ski masks, holding assault rifles, and issuing death threats to four Guatemalan police officers, who they accused of stealing a drug shipment in Raxruhá, Alta Verapaz (200 miles north of Guatemala City) in May of that year. They identified themselves as Jalisco New Generation and announced that the stolen haul belonged to El Mencho.

The police confirmed that officers in the area seized two abandoned pickup trucks on that date, and the Attorney General’s Office announced it would open an investigation, but the case was quickly buried even though CJNG has not remained idle. Mexican officials now regard Jalisco New Generation as the second-strongest drug cartel in Mexico, and Sinaloa’s main contender.

In December 2021, the Guatemalan Counternarcotics Prosecution Office announced the arrest of 12 CJNG associates, including three Guatemalan Air Force officers responsible for delaying authorities’ response to radar detection of illegal flights entering Guatemalan airspace, probably carrying Colombian cocaine. All three of the arrested officers were in key positions, one in the northern department of Petén, another in Retalhuleu on the Pacific coast, and the third in the capital.

Petén was the hub for 48 percent of cocaine planes landing in Guatemala —50 out of 107 small airplanes or jets, each with the capacity to hold from 300 kilos to two tons of cocaine— between 2019 and March 2021. Retalhuleu received 18 percent of the flights. The remaining 34 percent landed anywhere in between. Authorities seized shipments in one of every five cases, usually because the aircraft landed in remote areas. Another nine flights touched down in Petén during the rest of 2021, and six more have since January 2022. Only one, intercepted in March in Baja Verapaz, 106 miles north of Guatemala city, was followed by a drug seizure: one ton of cocaine.

The FARC Link

By January 2022, Colombian authorities announced that coke labs run by FARC dissidents (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, demobilized in 2016) were supplying Jalisco New Generation in Guatemala with tons of cocaine. Proof came in the form of a jet that took off from a clandestine landing strip in Venezuela, according to Colombian prosecutors, and landed in Petén on December 15, 2021. Guatemalan authorities seized one ton of cocaine. The bricks had all the signs of drugs produced in a lab in Colombia run by the FARC dissident group Second Marquetalia.

This FARC-CJNG link has a backstory.

“Jalisco New Generation learned plenty from its contacts in Colombia, where El Mencho adopted FARC tactics, which is why security forces in Mexico are so afraid of him,” says Michael Vigil, a former DEA agent who served as international operations chief in the 90s. “El Mencho was very astute; he now earns billions of dollars, which he invests in bribing politicians and members in the security forces, and equipping his men well, with military firearms, uniforms, and armored vehicles,” he says. The pictures and videos of individuals claiming to be CJNG, with bullet-proof vests, combat boots, and assault rifles, show it.

In January 2022, the DEA announced that “Operation Semper Infidelis” led to dismantling a CJNG trafficking network that purchased weapons in the U.S. and smuggled them to Mexico — quite possibly the same firearms they use in Guatemala. Mexican officials report that in 2021 at least 60 percent of the guns in the black market were purchased in the United States. In other words, weapons bought in the U.S. are used to protect cocaine bound to the U.S. consumer market.

According to the State Department, 90 percent of the cocaine seized on U.S. soil was smuggled via Guatemala and México. Between January and May 2022, that percentage amounted to 9.5 tons. Guatemalan authorities have only seized the equivalent of 10 percent of it. Since 2019, this seized percentage has varied between 30 and 50 percent per calendar year.

El Mencho is both familiar with firearms purchased in the United States and the supply of drugs on U.S. soil. He spent three years in a Texas prison in connection to drug trafficking charges in the 90s in California. Afterwards, he returned to Jalisco, Mexico, to work as a county policeman, only to resume his activities as a member of the Milenio Cartel, predecessor to the Sinaloa Cartel, according to Vigil.

Ten years later, El Mencho had joined the Valencia Clan, which smuggled cocaine from Guatemala to Mexico via Huista property. By 2010, he had co-founded Jalisco New Generation.

Influence Far and Wide

Since El Mencho first crossed paths with the Huistas in 2000, the latter’s influence seems to have extended to the political arena. One Huista member, Henry Hernández Herrera, arrested in 2021 in connection to a money laundering case linked to drug trafficking, had a sister who served as First Vice-President of Congress in 2021, Sofía Hernández Herrera. She is currently serving her third four-year term in Congress representing Huehuetenango. Henry Hernández Herrera was killed last January.

In 2021, Sofía Hernández’s nephew Jean Carlo Castillo Hernández was arrested due to a U.S. extradition request to face federal drug trafficking charges. Castillo was also linked to cocaine trafficking in Huehuetenango with the intent of sending it to the United States, according to his arrest warrant.

Aler Samayoa Recinos, identified as the head of the Huistas, has a daughter, son-in-law and mother-in-law serving as Guatemala’s representatives to the Central American Parliament (Parlacen) since 2020.

The Huista influence does not reach the entire country, but it’s enough to secure cocaine smuggling from Huehuetenango to Chiapas. According to Jiménez, they are highly effective and have a compartmentalized supply chain with replaceable links. Police only seized 8 kilos of cocaine in Huehuetenango between January and June 2022. In 2021, it seized 15 kilos out of 11 tons at a national level.

Designated by the U.S Treasury in March 2022 as an international drug trafficking organization, they are a likely partner for Jalisco New Generation, one of whose leaders was also designated one month earlier and identified as a Huistas associate.

CJNG influence in Central America seems not to have waned. In February 2022, videos released in social media showed an armed commando threatening other traffickers in Honduras, and warning them that they were in Petén, “on their way” to get them.

Local Honduran press reports also link Jalisco New Generation to former president Juan Orlando Hernández, arrested and extradited to the U.S. on drug trafficking charges. The Honduran government has not admitted officially to the cartel’s presence in the country.

In March 2022, the cartel had turned Michoacán, Mexico, into a war zone with armored military vehicles and drones to control a local gang and the Mexican army sent to fight both.

Central America is not new to Mexican cartels. The takeover began between the late 80s and 90s, when a heavily-surveilled Caribbean route gave way to smuggling via Central America by air, sea and land.

By the mid-90s the Zetas were guarding Guatemala’s plazas run by the Mexican Gulf Cartel, when the first Zetas (dissident Mexican military officers, previously trained by the Guatemalan military) also ran their security. By 2008, when they separated from a weak Gulf Cartel, they were familiar enough with Guatemala to try to run the plazas by themselves.

The CJNG’s entry point into Guatemala was also Huehuetenango and, like the Zetas, they spread along a main road at the north of the department known as the Transversal Northern Strip, to reach other departments like Alta Verapaz, the lower part of Petén, and Izabal, on the Atlantic coast. Izabal, another entry point from Honduras, was in 2021 the second province with the largest cocaine seizures after Petén, but authorities have not linked them to CJNG.

On March 31, authorities seized one ton of cocaine from a jet that landed in Baja Verapaz (south of Alta Verapaz, and 110 miles north of Guatemala City). It’s the only seizure made after six landings linked to drug trafficking between February and April 2022, but Counternarcotics Assistant Prosecutor Allan Ajiatas could not confirm whether the drugs were destined for CJNG hands.

There were two other landings in Petén, two in Alta Verapaz, one in Escuintla (Pacific coast), where there is confirmed Jalisco New Generation presence. In Mexico, they already operate in 23 of 32 states (28, according to Vigil). In Guatemala in 2021, they operated in seven out of 21 departments. The former DEA agent says they expand rapidly.