The Sandinista government is indicting priests, surveilling mass, and shuttering Catholic TV and radio stations. It’s a scene taken from the brutal Latin American armed conflicts of the 1970s and 80s, when military governments commonly treated critical clergymen as enemies of the state.

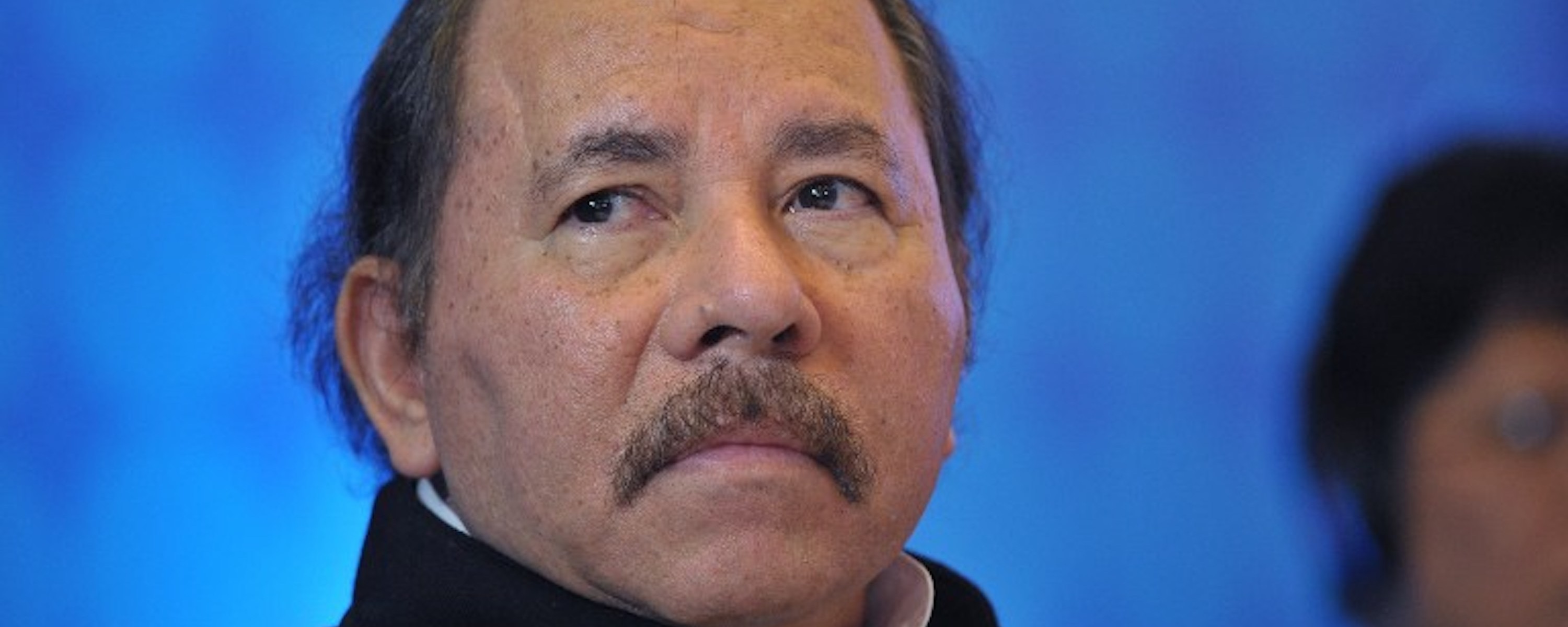

It’s a turning point, too, for President Daniel Ortega, an autocrat who regained power in 2007 promising a “revolutionary and Christian” agenda and tapping into a well of support from the country’s most populous faith. The Pope is now calling for national dialogue and the White House chimed in with an expected condemnation.

Nayib Bukele, who shows off a painting of the revered martyr St. Óscar Romero in Casa Presidencial and used to deride Ortega as a dictator, hasn’t said anything. El Salvador even abstained from an overwhelming vote by the OAS on Aug. 12 to condemn the attacks against the Catholic church in Nicaragua. So did Honduras, Mexico, and Bolivia.

Guatemalan President Alejandro Giammattei, who last June deflected from corruption allegations with appeals to religious conservatives in an express visit to Washington, has also stayed quiet. Nor has Honduran President Xiomara Castro weighed in. Her foreign minister justified the OAS abstention saying that “we respect Nicaragua’s internal affairs.”

Then there’s President Rodrigo Chaves, of Costa Rica, where authorities say they are on track this year to break their record for Nicaraguan refugees. The country voted in favor of the OAS resolution, and its ambassador condemned the attacks, but Chaves’ political foes argue that his support for Ortega’s leadership of SICA shows tepid support for human rights in the neighboring country.

In June we discussed how money from the regional development bank and a shared interest in avoiding domestic criticism for human rights abuses have provided powerful incentives for Central American leaders to avoid picking fights with Ortega. Now another element has come into view: They appear to prefer spending that political capital on drafting a proposal by 2024 —still light on details— to create a Central American Union.

It’s lost on no one in the region that the name sounds like the federation disbanded 181 years ago. Reunification dreams have been floating around for years, but Bukele has placed special emphasis on them, naming Vice President Félix Ulloa as his point person for planning to “convert Central America into a common homeland.” As we revealed in October, his party even has a clone in Guatemala.

One lingering doubt is whether respect for democracy will be a requirement of that union. In a Monday meeting in San Salvador, Ortega envoys thanked Bukele for the invitation to discuss the proposal, adding that the countries should “leave behind our differences.”

“Destabilizing and provocative”

The question might be how long Central American leaders can comfortably look away.

Three Catholic priests, two seminarians, a deacon, and a cameraman from the Episcopal Curia of Matagalpa have now spent one week in jail, accused by the National Police of organizing violent anti-government groups. Authorities occupied their facilities and ordered house arrest for Msgr. Ronaldo Álvarez, a prominent mediator of peace talks between dissidents and the Ortega-Murillo regime in the wake of mass protests in 2018.

With political opposition leaders in jail, the independent press exiled, and 1,606 civil society organizations annulled, in recent months the Catholic church was one of the few remaining civic spaces for dissent. Priests told the New York Times that Sandinista authorities even surveilled their worship services.

In an Aug. 19 press statement on the Matagalpa arrests, the National Police said authorities “waited with much patience, prudence, and responsibility for a positive statement from the Bishopric of Matagalpa, but it never came. Destabilizing and provocative activities persisted, so a public-order operation became necessary.”

On Wednesday, priest Leonardo Urbina was put on trial for the alleged rape of a 14-year-old girl in a case heavily publicized by state media. The court denied his family’s petitions for a private attorney to defend him.

Four other priests were forced to leave the country while others were barred from attending mass. The pope’s representative Waldemar Stanislaw Sommertag was expelled in March, and at the end of May, authorities kicked out a group of Catholic nuns running a shelter for children and the elderly.

Sandinista authorities have also now raided and closed 11 of the church’s radio and four television stations, per Confidencial. (After occupying the offices of century-old independent newspaper La Prensa one year ago, on Tuesday authorities consummated the move against what they call a “right-wing pamphlet” by expropriating the facilities.)

But the regime isn’t picking a fight with everyone under the Christian umbrella. The presidential couple began drifting toward the Evangelical church after the 2018 mass anti-government uprisings to rehabilitate its image.

“In order to hold an 'open' dialogue, as the Pope proposes, Daniel Ortega must first unconditionally free all the political prisoners, including Monsignor Rolando Álvarez and the seven religious figures currently held in El Chipote,“ writes Confidencial Nicaragua director Carlos Fernando Chamorro. “Only without a police state will the 'open and sincere' dialogue prescribed by Pope Francis become possible.”