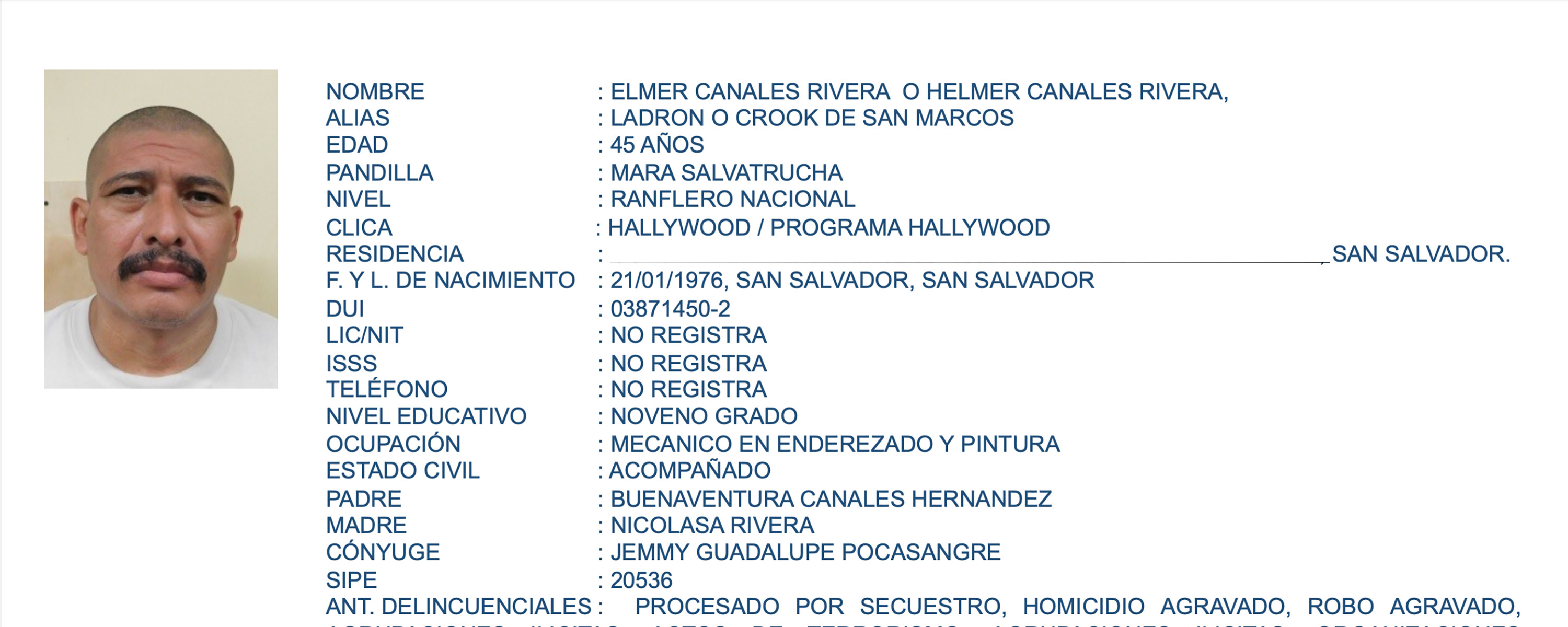

The National Civil Police (PNC) of El Salvador knew within 24 hours that Élmer Canales Rivera, one of the most senior leaders of the Mara Salvatrucha-13 known as “Crook de Hollywood,” was illegally freed from the maximum-security Zacatecoluca Prison on November 18, 2021. Four months later, the Bukele administration’s top negotiator with the gangs told a leader of MS-13 over the phone that he had personally taken Canales out of prison.

In the afternoon on November 19, the PNC issued a string of internal alerts over email that Canales, who they profiled as a nationwide leader of MS-13, was released from Zacatecoluca.

At the moment of his release, Canales was facing a 40-year prison sentence issued in 2020 for double-homicide, which he had asked the court to review, as well as another 11 months on a three-year sentence for trafficking illicit objects in prison. He was also notified five months earlier, in June, of an international arrest warrant issued by Interpol, accusing him of “transnational terrorism” and “drug trafficking” on U.S. soil.

On top of that, the Police traveled to Zacatecoluca Prison on November 18, on the day of his release, to notify him of an outstanding warrant for homicide dating back to 1999, but a member of the police team tasked with executing the warrant told El Faro that prison authorities denied them entry and prevented them from carrying out the assignment.

These are all revelations from emails, police files, and prison intelligence reports from the PNC, obtained by El Faro via whistleblower sites DDoSecrets and Enlace Hacktivista, who received over 4,000 gigabytes of information stored on the servers of the PNC and Salvadoran Armed Forces from the hacking collective Guacamaya. In the same leak the collective also extracted thousands of gigabytes of information from the armies of Mexico, Peru, Chile, and Colombia.

In El Salvador, the police files document Canales’ release in November, 2021, adding more evidence to the trove already published by El Faro, including the audio in which the Bukele administration’s chief negotiator with the gangs, Carlos Marroquín, confessed to a gang member that he personally took Canales out of prison and drove him to Guatemala to “show you [the gang] my loyalty and trustworthiness.”

To date, Salvadoran police and prison authorities have not publicly admitted that Canales was freed, but in April, five months after he exited prison, a drug court in Guatemala City granted that he had passed through their country by signing an arrest warrant to extradite Canales to New York. In May, a deputy commissioner of the Salvadoran Police asked for help from regional police partners to capture and send him back to El Salvador, showing signs that one part of the state was still tracking down Canales months after another had set him free.

Illegal Release

The historic leader of MS-13 left maximum-security prison despite multiple ongoing sentences adding up to more than four decades in prison, pending criminal accusations against him, and an international extradition order.

On Oct. 30, 2019, the First Sentencing Court in Zacatecoluca sentenced Canales to three years’ prison time for trafficking prohibited objects in prison. Fewer than four months later, on Feb. 6, 2020, San Salvador’s Specialized Sentencing Court “A” condemned him to another six decades behind bars for two homicides, as part of the “Cuscatlán” case, a police operation launched in 2018 to attack the leadership and finances of MS-13.

Canales’ attorneys asked the court for a reduction of this latter sentence and in April, 2021, the First Criminal Appeals Court recategorized one of the two homicides as a conspiracy charge, shaving two decades off his total sentence. In July, 2021, Canales asked for a second sentence reduction, but by March, 2022 —four months after his release— the court had not finished its evaluation, according to a joint investigation by La Prensa Gráfica and InSight Crime.

In a file on Canales shared with the police in early June, 2021, and obtained by El Faro through Guacamaya, the Prison Bureau confirmed that it knew that he had received four decades of prison time in the Cuscatlán case: “They [the court] confirmed his sentence of 40 years. According to the ruling, they modified one of the convictions from homicide to conspiracy, for which he would serve 10 years, and they confirmed the other sentence of 30 years, making for a total of 40 years.”

At the time of his release, there was no legal room to argue that the conviction was still disputable, even though the court had yet to decide whether to subtract more years from his sentence. “If the court granted the [sentence] revision, then the conviction was confirmed,” Judge Antonio Durán, of the Second Sentencing Tribunal of Zacatecoluca, told El Faro. “Revisions can only proceed in cases with confirmed convictions.”

Reports from the Interpol office of the PNC also confirm that Canales was notified inside Zacatecoluca Prison on June 3, 2021, of an international arrest warrant, issued by request of the United States to try him for transnational “narcoterrorism” in the Eastern District of New York alongside more than a dozen other senior leaders of MS-13.

Canales had already spent two decades in prison when the Bukele administration freed him. In December, 2001, he was condemned to 16 years in a kidnapping case known as “Costa Azul.” In 2016, months before completing his first sentence, he was accused of being a “leader of a terrorist organization” in a well-known precursor case to Cuscatlán known as “Jaque.”

He was absolved of all charges in Jaque, but other ongoing cases were enough for authorities to keep him in prison until he was condemned in October, 2019, for trafficking illicit objects in prison facilities, as well as his double-homicide conviction in 2020. El Faro obtained his file in the Prison Information System (SIPE) from November, 2021, which identified another case against him, opened in 2020 by the Specialized Sentencing Court “A” in San Salvador for aggravated extortion and illicit association.

The Day of His Release

Fifteen minutes after noon on Nov. 18, 2021, two agents from DCJ, the office of the National Civil Police that serves outstanding arrest warrants, traveled to Zacatecoluca Prison to notify Canales of a pending warrant issued in 1999 by the First Trial Court of Cojutepeque, Cuscatlán. Their arrival was recorded in a prison intelligence report that the police subdelegation in Zacatecoluca sent at the end of the day up the chain to the delegation and Joint Command in La Paz.

The report, submitted without the name of the agent who wrote it, only states that a corporal and an agent from the DCJ office in the department of Cuscatlán, where the Cojutepeque courtroom is, arrived on board a vehicle “from DCJ” “in order to notify” Canales about the warrant. In El Salvador, when incarcerated people are notified of additional charges against them, they generally remain in the same facility.

Four hours later that same day, a head administrator from DCJ Cuscatlán wrote an email to Zacatecoluca Prison requesting that the same corporal be allowed access to the facility to “notify” Canales of an outstanding warrant. The administrator did not say which warrant and the prison intelligence report filed that day did not log a second visit by the police unit.

A member of the unit, contacted by El Faro on Tuesday, claimed that the intelligence report omitted that authorities did not let in anyone from his team that day, under the argument that their superiors needed to “request entry from the Prison Bureau.” “Nobody was notified [of arrest warrants] that day,” said the source, adding that “a few days later I found out from one of my superiors that [Crook] had been freed.”

What does appear, in documents from both the Police and Prison Bureau, is that Canales exited prison sometime during the same day that DCJ had arrived to serve the charges.

The first official document to register his release was a report obtained by El Faro, sent on November 19 by the Center for the Analysis of Prison Information (CAIP), a department of the Prison Bureau, to three police intelligence offices: the Central Unit for the Analysis and Treatment of Information (UCATI), the Division of Analysis and Production of Intelligence (DAPI), and the Department of Prison Intelligence of the Division of Collection of Information (“Penales DIRI”).

The report is an Excel file listing all of the incarcerated people released the previous day: 29 people across 12 prison facilities around the country. For each, CAIP listed the legal justification for their exit, with the exception of one: Élmer Canales Rivera, Crook. The cell that should contain the motive of his release was submitted empty.

In the same email sharing this report, CAIP included a PowerPoint with the prison files of the eight most notable detainees released that day. According to the Prison Bureau, they were all gang members of lower rank than Canales, who has been part of the “Ranfla Histórica,” or most senior leadership of MS-13, for at least two decades. CAIP excluded his file.

Hours after CAIP sent the report, Canales’ name on the Excel sheet appears to have triggered a flurry of email alerts within the Police.

Between 3:40 and 4 p.m. on November 19, Penales DIRI sent out five emails alerting other police intelligence offices. It sent the first two to Chief Inspector Alfredo Pérez, the head of DIRI, and to another agent from that office, with the subject line in capital letters: “National ranflero [member of the Ranfla] of MS-13 freed.”

Next, DIRI sent out another three emails —with the title, “National MS-13 leader freed”— to other offices: the Division of Intelligence Operations (DOI) and the teams from the Department of Police Intelligence (DIP) in the south and center of San Salvador.

In each of the five emails, the Police noted that Canales still owed four decades of prison time: “Condemned to 30 years for aggravated homicide and 10 years for aggravated homicide.” The file also confirmed the Prison Bureau’s initial report: “Freed on 11/18/2021, Zacatecoluca Maximum-Security Prison.”

El Faro registered only one response to these emails, from the DIP team in the south of San Salvador: “I'm aware. If your units surveilled or followed him please send his location.” Hours after the Bukele administration ordered his release, the PNC was trying to find him.

The PNC communications office did not respond to an email from El Faro on Friday, October 21, requesting information on Canales’ release. That same day, El Faro sent messages over WhatsApp to Vice Minister of Security and Prison Bureau Director Osiris Luna Meza and Alejo Carbajal, a Prison Bureau spokesperson, but received no reply.

International Arrest Warrant

Documents leaked by Guacamaya reveal that Canales was on the verge of release five months earlier, on June 3, 2021. At the end of the day, CAIP reported that he had been freed, but that same day the PNC’s Interpol office recorded that an agent entered Zacatecoluca Prison and informed Canales of the pending red notice, or international arrest warrant, from the United States. Three weeks later, Interpol reported that he was still detained in the same facility, and that did not change until he definitely left prison five months later, on November 18.

In its June 3 report, CAIP wrote: “PDL [incarcerated person] freed on 6/3/2021 from the maximum-security prison in Zacatecoluca because he had already spent the maximum amount of time in provisional detention for the Cuscatlán case. Wanted by Interpol.”

The “maximum amount of time in provisional detention” refers to the 24 months allotted by law for authorities to keep a detainee in custody while awaiting a sentence, with the option of 12 more months in the case of appeal. After the judge ruled on the Cuscatlán case in February, 2020, the defense attorneys for Canales and others in the case appealed, on the argument that they had spent more than the legally allowed time in detention.

On April 26, the Specialized Criminal Appeals Court made an apparently contradictory move: On one hand, it confirmed their sentences, and on the other it decreed release from provisional detention for some of those convicted.

As Godofredo Salazar —the organized-crime judge who issued the Cuscatlán ruling— explained in a letter to the warden of Zacatecoluca Prison in March, Canales could not be released despite having spent longer than allowed in provisional detention for that specific case, because he still faced ongoing sentences and trials.

The Cuscatlán sentence, obtained by El Faro, condemned hundreds of people for a series of alleged crimes. Among them were six members of the Ranfla Histórica: Crook; Eduardo Erazo Nolasco, 'Colocho de Western'; Efraín Cortez, 'Tigre de Parkview'; Borromeo Enrique Henríquez, 'Diablito de Hollywood'; Saúl Turcios Ángel, 'Trece de Teclas'; and Carlos Tiberio Valladares, 'Snayder de Pasadena'.

Amid the confusion, the Police mainly used the red notice from Interpol to argue that Canales could not be freed.

El Faro obtained correspondence on June 1 and 2, 2021, between the director of the Transnational Anti-Gang Center (CAT) of the PNC and the warden of Zacatecoluca in which the warden requested a report from CAT on outstanding warrants for Canales and Erazo. He explained that the appeals court had “confirmed their prison sentences” but “ordered that they be freed from provisional detention [...] due to the expiration of the 36 months [...] and ordered alternative measures to detention.” The warden concluded: “Given that the ruling comes from a superior court, it should be carried out. [The court] has ordered the release of the PDLs [detained people].”

In a response the next day, CAT Chief Inspector Ronald Mauricio Segura sent the warden the red notices from Interpol for Canales and Erazo and confirmed that in his database he found “outstanding arrest warrants and investigations” for both of them.

On June 3, somebody prevented the release of Canales and Erazo. An Excel file sent by email on June 22 by the Department of Analysis of Interpol’s National Central Bureau in El Salvador to Commissioner Manuel Ulises Garay Coto, the head of the office, reported that agents from that office notified both gang leaders of the red notices on June 1 inside Zacatecoluca Prison, and that, three weeks later, they remained there.

Extradition Request in Guatemala

Documents leaked by Guacamaya also show that on April 8, five months after Canales’ release, the chief judge of Guatemala City’s Third Tribunal of Criminal Sentencing, Drug Activity, and Crimes against the Environment signed an arrest warrant for Canales in response to a U.S. extradition request and joint investigation by Interpol and the country’s Public Prosecutor’s Office (MP).

On October 11, a representative of the court stepped out into the hall outside their offices to speak with El Faro, only confirming that, “Yes, it’s him [Crook], and yes, he has an arrest warrant.”

MP spokesperson Moisés Ortiz told El Faro on Friday that “the Specialized Unit for International Affairs has a file relating to Élmer Canales Rivera “Crook,” a Salvadoran national,” but declined to say more, citing case confidentiality.

In July, El Faro published an investigation recounting Canales’ movements after his release: After staying for several days with his romantic partner in a luxury apartment in San Salvador, he fled to Mexico via Guatemala.

On May 3, PNC Deputy Commissioner Carlos Enrique Somoza Villareal, head of the Transnational Criminal Investigation Division, admitted Canales’ release in an email to the State Department contact of the Joint Border Intelligence Group (GCIF), a consortium of border authorities from the United States, Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras that share information from their respective databases.

Somoza requested help from GCIF to arrest and send Canales back to El Salvador, along with Franklin Eduardo Pérez, also known as Héctor Geovany Carpio Ávalos, or under the aliases “Pirulo” or “Scooby.” The deputy commissioner added that the Salvadoran Police had “received information” that both were in “Guatemala or Mexico” and attached a police file that again confirmed that Crook “was freed” from Zacatecoluca on November 18 of last year.

Somoza saw but did not answer a message from El Faro over WhatsApp on Tuesday, asking when he learned that Canales was free, who released him, and what information he had obtained from regional partners. Nor did GCIF answer an email sent on Friday requesting information on the case. El Faro did not receive a reply to requests for comment from the U.S. Embassies in El Salvador and Guatemala, the official channels for requesting extraditions.