On Wednesday, December 7, the Honduran Police and Army began deploying forces to dozens of neighborhoods in the two largest cities of Honduras who, the night before, had multiple of their constitutional rights suspended by executive decree. Their communities are the new battleground of what President Xiomara Castro two weeks ago called a “war against extortion.” It’s a page from the playbook of neighboring President Nayib Bukele, who since the beginning of April has maintained all of El Salvador under a state of exception amid what he calls a “war against gangs.”

Castro, who at the end of January will complete her first year in power, promised to restore democracy in Honduras after a decade of narco-government — “narco-dictatorship,” as her government calls the 12 years of National Party rule. But in 89 colonias (or neighborhoods) of the capital and 73 others in San Pedro Sula she has suspended six constitutional rights by executive order: freedom of transit and protection from forced displacement from one’s home; freedom of association; “personal freedom;” the right to post bail and avoid pre-trial arrest; the prohibition of detentions without a warrant; and the right to “not be arrested for obligations not stemming from a crime.”

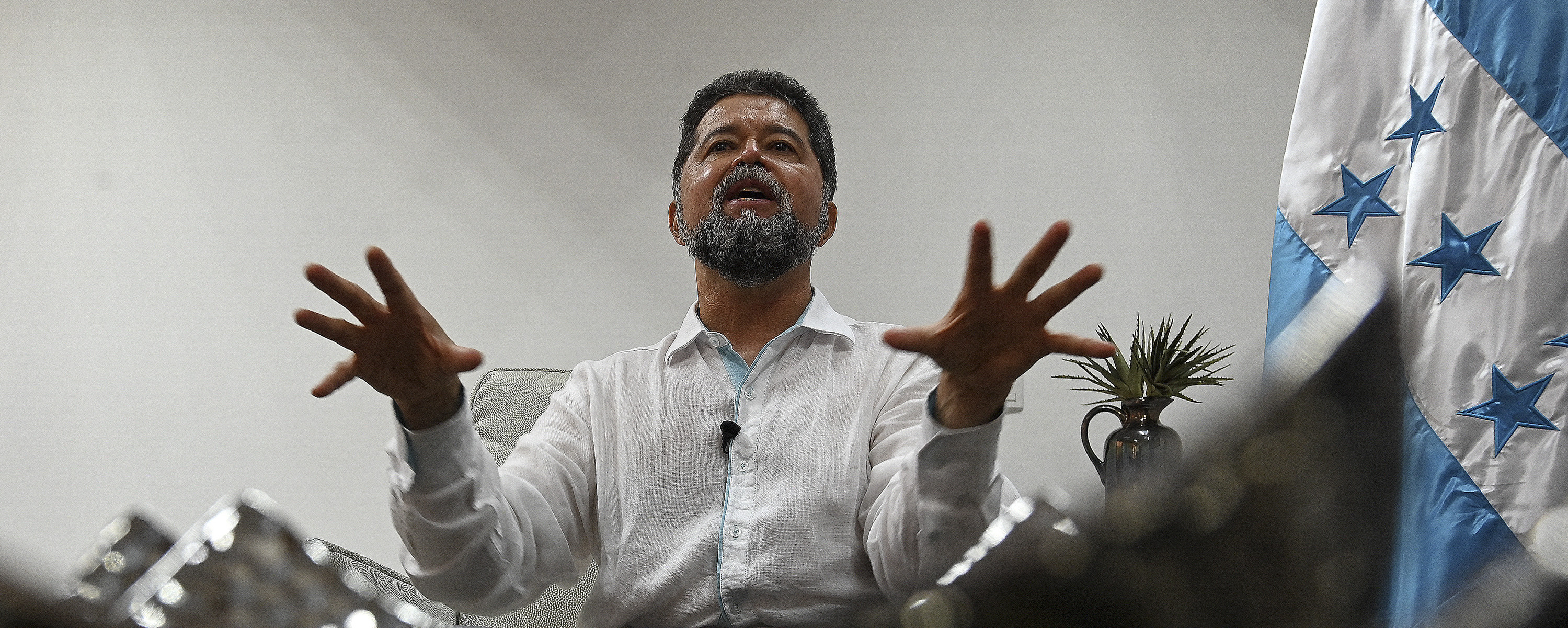

In El Salvador, a similar suspension of guarantees has led to almost 60,000 arrests in the past nine months, as well as thousands of reports of arbitrary arrest, torture, and due process violations. In Honduras, Secretary of State for Public Security Ramón Sabillón tempers Castro’s talk of war with promises of respect for human rights and to address the “root causes” of crime. He also tries to take distance from the excesses of Nayib Bukele’s model, despite the fact that in August the president of the Honduran Congress, Rolando Redondo, visited El Salvador, met with Vice President Félix Ulloa, and publicly stated that he came to see the results of what Bukele has called his “Territorial Control Plan.” Julissa Villanueva, vice minister of security, has also publicly asserted that Honduras should see what it can learn from the Salvadoran model.

But in the ten days since he spoke with El Faro over the phone on November 27, the measures described by the secretary —one of the officials who signed the executive order— have changed: the number of colonias targeted by the measures has increased from 120 to 162; he underscored just one suspended right but now there are six; and the government went over the heads of Congress, imposing the state of exception by executive order.

On Wednesday morning, El Faro contacted the secretary and a press assistant to offer a chance to update any of his statements. The assistant responded that “due to the fulfillment of his agenda I haven’t been able to contact the minister right now.” At publication time Sabillón had not returned a separate message sent directly to his phone.

Sabillón, who in the interview admits that political discourse prevails over technical criteria in decisions of this nature, says that there will be no abuses of power under the states of exception in Honduras, but a sizable portion of his answers in this interview have already turned out to be false.

Why extortion, and why combat them in this fashion now? It seems that the government believes this is the main problem facing Honduras right now, even above drug trafficking.

It’s not that one is above the other, but rather that they’re linked. The maras [gangs] diversified themselves through the distribution of drugs, contract killings, money laundering. They meet the criteria of organized crime in the Palermo Convention. We made the change to treat both problems equally.

Are you saying that by declaring war against extortion you’re also doing so against drug trafficking?

It implicitly carries a component of internal trafficking and distribution, two problems that we want to attack.

Is it also a war against the gangs?

Exactly — and against all of their typology, like the use and trafficking of arms and munitions.

Why the bellicose narrative? Can you not address these problems through your public security policy?

I’ve spoken of prevention and control. Other parts of the state working on social and economic issues also have a responsibility to the family unit. And we also see the component of human rights and human security. A society must attack crime at the root, not only repress. What happens is that people don’t like preventative measures. They want a hard fist.

So, this talk of war… Some things have been said and you know that technical analysis isn’t the highest level [of decision-making], but rather politics. That’s where the talking points are defined. So, in order for people to understand that we’re moving forward with strength, and with decisiveness, Madam President has appropriately used that term.

But there will be a suspension of constitutional rights in dozens of communities who could find themselves besieged by the Army or Police.

More than anything by the Police, but the Police works in a technical manner. We’re working so that the state of exception will be as minimally invasive as possible and so that there will also be periodicity, a schedule, like in other curfews and other activities of the nation, of the communities. With differential treatment, because every community has its own culture, its own social, economic, and educational activities.

But there will indeed be a suspension of constitutional rights.

Probably, in terms of circulation. Not for the citizens, but for certain groups.

The right to enter and exit certain communities?

Yes. But, for example, in the case of a health worker who is on call, there must be discretion because his work is of a social nature, as is also the case for security companies. We’re trodding a very fine line that will not affect the economic activities of each municipality. It will be focused solely on hotspots. Those 120 neighborhoods or colonias are mainly in San Pedro Sula and Tegucigalpa, but it will be progressive and studied in other communities, because criminals can move from one city to another.

El Heraldo has reported ten articles of the Constitution that could be suspended under states of exception. Is that not what the government is requesting?

No, I think they’re putting things out of proportion. They see the norm in an absolutist way. But no, there will be no deprivation of… Remember that our proposal needs to pass through the hands of the Executive and Congress. I repeat: It will be as minimally invasive as possible in the life of a community.

How do you expect this to fare with the different legislative groups?

Just fine. They have asked for [the decree], because this is a national issue.

Are you using the state of exception in El Salvador as a reference point?

No. Look, every country has its own realities and makes its decisions. We are taking an alternate route. More than a month ago [in October] the Office for Rehabilitation, Resocialization, and Reinsertion was created. We can now take both steps, as opposed to the other model, so that ours will not be invasive of dignity nor human rights.

Doesn’t a state of exception imply that the government is incapable of addressing extortion without suspending rights?

No, we always frame our work in dignity and human rights. In the short term, with our formula, with our eight strategic focus points, we will be able to get this done. We’ll publish those points later, but the strategy is very attuned to reality in Honduras. There are components from El Salvador that could be used, but not in their total dimension. There are things to be learned from them, but in the catracha [Honduran] formula.

What things can be learned from Bukele’s model?

The first is respect for socio-economic activity and culture of each community, each colonia. Respect for transportation and the active identification of individuals to see if those moving around are credible, without ties to these structures.

In El Salvador there have been almost 60,000 arrests and thousands of reports of violations of rights. The rights to defense and communications privacy, for example, have been suspended. You say that you would like to incorporate aspects of what is happening in that country, so I’d like to understand what you’re referring to.

In transportation and circulation we will have some differences. Ours will go by colonias, but not all of them in San Pedro or Tegucigalpa. I don’t think it will be a total restriction of rights in those two initial municipalities. Remember that we’re in the December holiday season, with celebrations. We have to know how to apply it, so that it won’t be invasive.

Does Honduras need to purge the police or military?

I can only speak for the Police. Recall that from 2016 to 2018 they removed almost 5,000 police officers in processes that were not judicially reliable. Our proposal for recruiting or firing personnel will be carried out in accordance with the law. And we’re improving our human talent, because the Police cannot only repress. We have to also apply other educational models: human dignity, human rights, the rights of women and ethnic groups.

Speaking of which, have you investigated the involvement of the Police in the removal of the Garifuna community in Punta Gorda?

It’s not a question of involvement, but rather of intervention. “Involvement” suggests a violation of human rights, but that police intervention was ordered by a court. A prosecutor and the ordering judge accompanied the process. We carried it out and yesterday [November 26] was the hearing in which the six people were freed. The Police are only one actor in the system. Not everything falls at our feet. What would happen if a police officer disobeys a court order? In addition to being detained, his right to promotion is lost and he loses his job. People can view the functioning of the Police in a simplistic way, but it’s complex.

The Police has to obey judicial orders, but the Garifuna community has the right to ancestral land…

That’s another issue… How do you define the concept of ancestral?

I’m not the one to define it. It’s the Inter-American Court.

That’s not up to the Police, but rather the Judicial Power. It’s the decision of the state in its entirety, the courts.