Congressional paralysis over the selection of Honduras’ attorney general has gone from dismal —parties failed to make a pick by the legal deadline of August 31— to worse. The ruling party Libre doubled down by forcing a partisan interim prosecutor, street violence made an appearance, and over the weekend both Libre and an opposition bloc convened parallel demonstrations as they dueled to control the narrative.

On October 31, hours before legislators broke for vacation until January 24, President of Congress Luis Redondo filled a nine-person recess commission with eight members from Libre, which holds just 49 of 128 seats in Congress. The next day, the commission appointed Libre municipal official Johel Zelaya as interim AG, despite nomination rules against party affiliation.

As interim deputy prosecutor, they chose Mario Morazán, a former diplomat in the government of Manuel Zelaya (2005-2009), who is husband-advisor to President Xiomara Castro and her administration’s de facto power broker. Barring a surprise consensus nomination, the two men could head the Public Prosecutor’s Office for the rest of Castro’s term.

“It is a political maneuver by the government,” constitutional lawyer Joaquín Mejía told El Faro English. “Libre paralyzed Congress by making trips to Russia, China, and not convening sessions, with the goal of getting to October 31, when the ordinary sessions ended, to be able to name the interim commission.” “Which is legal,” Mejía underscored.

Redondo told reporters on September 4: “We will not give impunity to criminals who are still looking for impunity. All of the prosecutors from the different offices continue working normally, with their cases and investigations (...). We are going to increase the budget of the Public Prosecutor’s Office. We want it to be strong, so that when CICIH [the International Commission against Impunity in Honduras] arrives, they can have a true prosecution arm for the cases they find.”

In a dismissal of the commission’s authority, opposition legislators convened their own session of Congress that same day, October 31, and controversially ordered an extension of the regular legislative calendar through January, in an effort to nullify the commission and to keep in place the controversial top interim prosecutor, Daniel Sibrián.

President Redondo has argued the commission has the power to choose an interim AG after the outgoing prosecutor, Óscar Chinchilla, left for Managua in September to start a 10-year term as VP of the Central American Court of Justice. Chinchilla, overshadowed by his closeness to Juan Orlando Hernández, had been illegally appointed to a second term in 2018.

Fanning the flames, Libre supporters grouped in ‘colectivos’ confronted National Party legislators on the steps of Congress, injuring multiple of them, according to independent outlet Contracorriente.

Honduran jurists are divided. “In Honduras the law isn’t upheld, but rather interpreted like the Bible,” Bar Association President Rafael Canales told TV Azteca. “This constitutional question will go to the Supreme Court, which is unfortunately also polarized.”

Electoral impact

“The ‘law of the strongest’ is prevailing. Congress decided to self-interpret the constitution,” journalist Thelma Mejía told El Faro English. “When a question is inconvenient, it is unconstitutional. And when it is in their interest, it is totally constitutional.”

This is not the first time that the current Congress, unable to strike a minimum consensus, erupts in fistfighting: in January 2022, Castro’s Libre party fractured in two over Redondo’s presidency. That division, resolved on paper, continues to simmer under the surface.

But the coming hurdles could be even higher: When sessions resume, Congress will be tasked with forming a new executive board around Redondo, president until 2026.

Meanwhile, in the recess, the commission could make key appointments to the Superior Tribunal of Accounts, Supreme Electoral Tribunal, and senior command of the Armed Forces, institutions that will supervise the 2025 elections.

Honduran analysts are increasingly grim. “Castro generated expectations that the country would change, because we came from an authoritarian right-wing government that suppressed human rights and had narco ties,” Lester Ramírez, coordinator of the Association for a Just Society (ASJ), told El Faro English. “But what we now have is a repressive left-wing government with authoritarian behavior. That is due to the internal dynamics of Libre: Factions are fighting for power, and the one that has taken control is the more radical group.”

“The crisis in Congress is not new. It’s a new manifestation of the permanent crisis since the 2009 coup d’état,” says Joaquín Mejía.

Former president Manuel Zelaya was illegally deposed while promoting a referendum on his reelection, which is —like in most of Central America— unconstitutional. “The Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s [post-coup] recommendations have not been implemented,” Mejía added, “including the investigation and sanctioning of those responsible and legal reforms to ensure non-repetition. That is why the wounds remain open.”

Who can mediate?

On November 7, Foreign Minister Enrique Reina announced that he would formally complain to U.S. Ambassador Laura Dogu about “interference” in internal affairs. The issue was her public stance on the interim AG appointment, summed up in a tweet on November 1: “Today’s actions [in Congress] will only polarize the country more.”

Assistant Secretary of State Brian Nichols had weighed in, too, writing before her that the selection “further undermines trust in the country’s institutions. We call on all Hondurans to avoid violence and seek consensus (…) with the 86 required votes.”

“This crisis is a failure of the political elites that shows the absence of leadership, to the point that three opposition parties asked for the OAS and UN to mediate a dialogue with the president of Congress,” says Thelma Mejía.

Perhaps due to recent history, it is harder for the U.S. to mediate in Honduras than in Guatemala, where they have hosted talks between Arévalo, Indigenous leaders, and the private sector amid attacks on the recent election results. Former U.S. ambassador to Honduras Hugo Llorens condemned and tried to avert the 2009 coup, according to WikiLeaks published by El Faro and as Zelaya himself acknowledged. But U.S. recognition of Juan Orlando Hernández’s 2017 unconstitutional reelection, including widespread allegations of voting-day fraud, and persistent U.S. support for Hernández despite evidence of his ties to drug trafficking, continue to fuel deep distrust.

Their stressing of sovereignty and taste for social media confrontation —like Castro’s public attacks on U.N. resident coordinator Alice Shackelford, for appearing in a panel with the National Anti-Corruption Council— appear to be spooking other international actors.

“In Honduras there are no longer any mediators,” lamented Ramírez of ASJ. “We used to have the church, or public intellectuals. I haven’t heard a single international cooperation organization invite civil society to discuss [the AG selection]... There is slowness and a sense of, ‘I’m watching out for my job.’”

Precedent for CICIH

The imposition of a government-aligned interim AG is also the most recent of signals that the political conditions for the prize international project in Honduras —Castro’s promise of a U.N.-backed anti-corruption commission called CICIH— may be fading.

“It isn’t a step in the direction we’re seeking,” a source close to the CICIH construction process told El Faro English this week, underscoring the difficulty of establishing an international commission if the different political parties cannot find minimal consensus on anti-corruption issues. The U.N. has not made a public statement on the recent events, perhaps in an effort to avoid politicizing its negotiation with the Honduran government or to avoid renewed outcry from the Castro administration.

The coming weeks could be decisive: the U.N. is expected to evaluate the implementation of the memorandum of understanding it signed with the government last year. “The government has met all of its obligations,” argues Joaquín Mejía, still optimistic.

Redondo, a communications staffer for Congress, and a spokesperson for the Castro administration did not return requests for comment from El Faro English on the selection of the interim prosecutors or the ramifications for the CICIH.

But neither Castro nor the U.N. have been keen on pointing out an elephant in the room: the amnesty law sponsored by Libre in March 2022 that gave immunity to former Zelaya administration officials —allegedly— to stem persecution from 2009 coup leaders.

A number of those officials are under real suspicion of corruption. In the last two years, the U.S. State Department revoked multiple visas including that of Castro advisor Enrique Flores Lanza, Zelaya’s minister of the presidency accused of siphoning $2 million from the central bank relating to the 2009 reelection referendum. Amid the CICIH negotiations and an increasingly tense relationship with Tegucigalpa, this July Washington’s sanctions steered clear of the Honduran presidential circle. Unless Congress renews the ‘Engel List’ sanctions authority, it will expire on December 27.

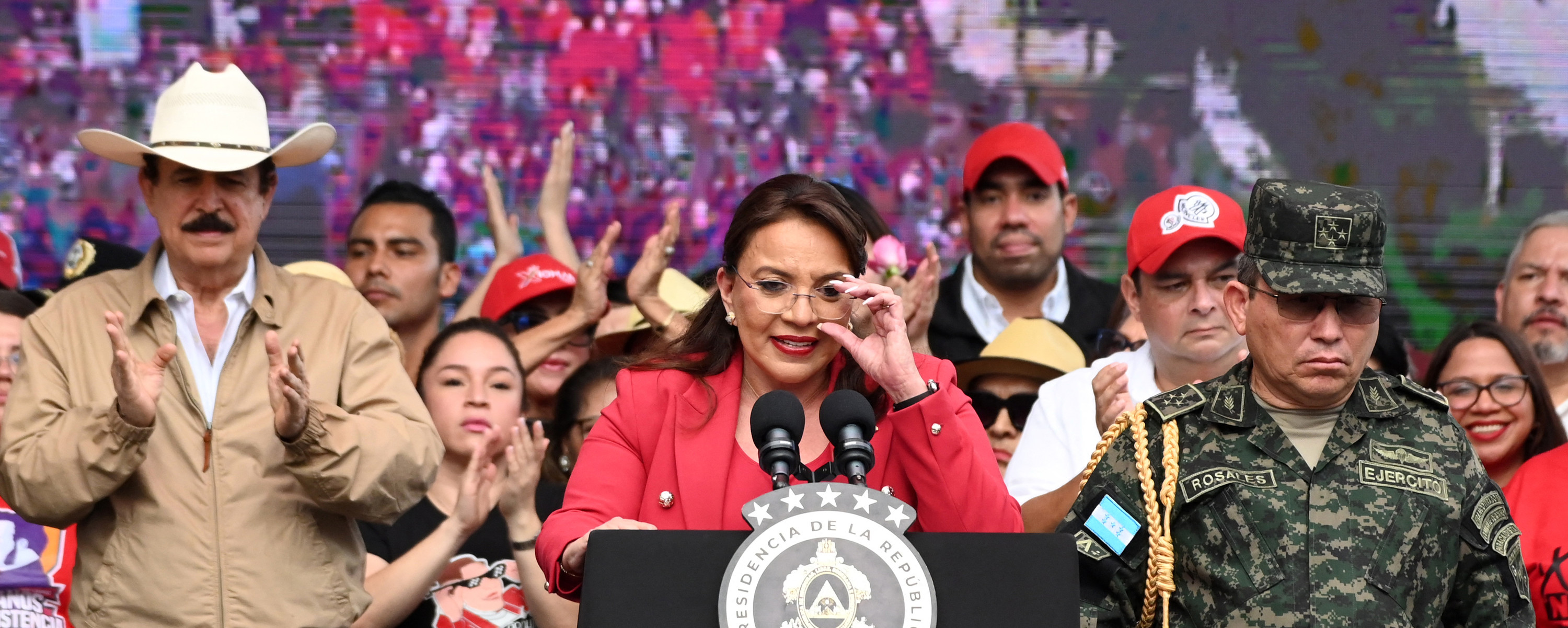

“The National Congress is obligated to choose the authorities of the Public Prosecutor’s Office according the dates established by the Constitution,” President Castro told demonstrators in a speech on August 29, two days before the selection deadline. “I have not lost hope for finding a consensus in Congress, despite knowing that they have the majority. (…) Nobody can stop my government’s frontal attack on corruption. The CICIH is coming.”

Over two months later, and with Congress plunged deeper in a legal and political crisis, pessimism is growing in civil society. “Nobody wants [the CICIH], because they want to protect their impunity,” says Thelma Mejía. Ramírez, of ASJ, agrees: “I think the model of international commissions has already gone out of style in Central America,” he argues. “[The CICIH] is part of the government discourse, but it’s more than evident that the conditions are not right.”