El Faro is an investigative newsroom that translates Central America. Subscribe to our newsletter.

For weeks Guatemalan President-Elect Bernardo Arévalo kept his very first executive decision, his cabinet ministers, a carefully guarded secret, amid widespread suspicion that AG Consuelo Porras would seek to criminalize names on any preliminary list.

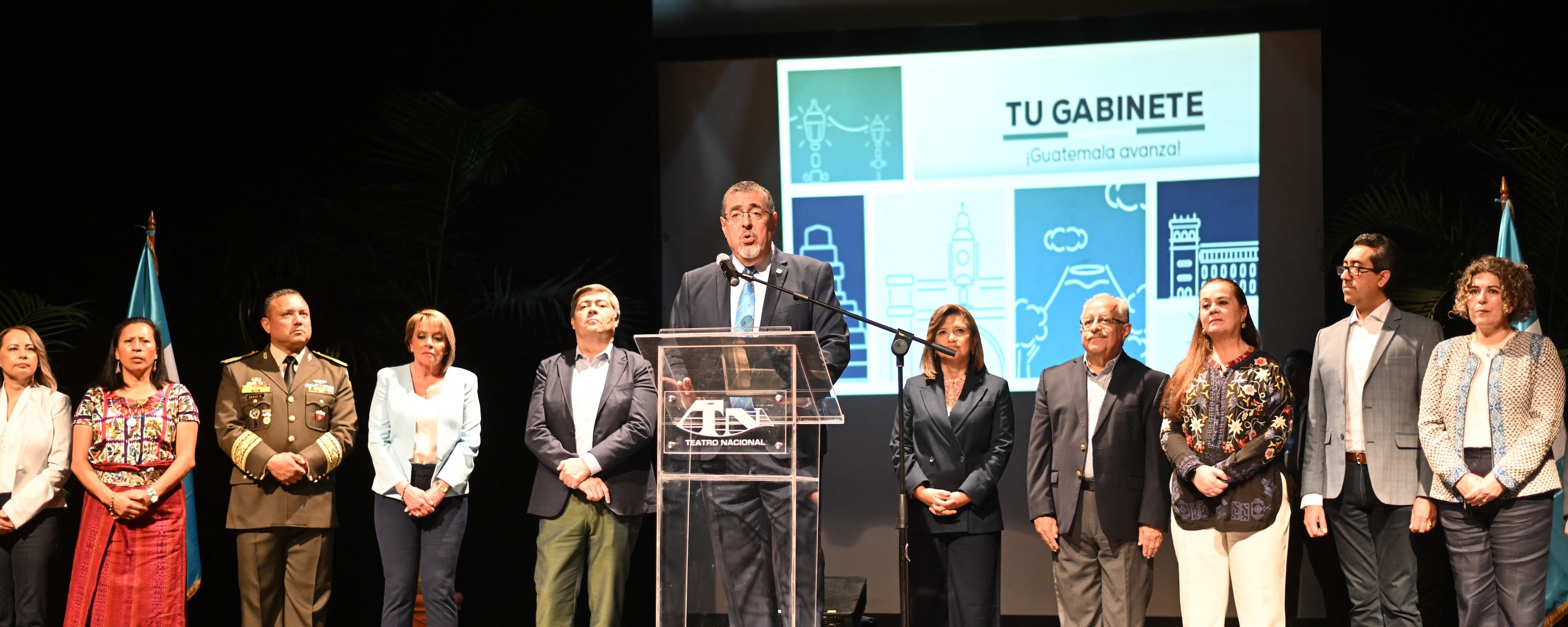

In a public event on Monday, six days before their Sunday inauguration, he finally introduced the 14 ministers, seven women and seven men. But his underscoring of gender parity, a first in Guatemala, quickly opened a flank of criticism of the same cabinet.

Only one cabinet member is Indigenous —Labor Minister Miriam Roquel— in a country where over 40 percent identify as Mayan, and despite widespread recognition that Indigenous-led demonstrations were vital in stopping elite-sponsored efforts to annul the election result and even imprison Arévalo.

The 48 Cantons of Totonicapán —one of the most influential Indigenous authorities, who met with Arévalo during the transition and organized mass protests in defense of the election— wrote in a statement on Tuesday: “We call on the government, during its first 100 days in office, to consider our voices and demands. (...) We Original peoples do not lose hope of one day being part of a government that is inclusive, not in discourse alone.”

Some critics were more strident yet. “This colonial state is not ours, and hoping for a Ladino man to save us as peoples is cold, hard colonialism,” wrote Kaqchikel Mayan anthropologist Sandra Xinico on X. But others rebuffed the very focus on ethnicity, citing that top prosecutor Rafael Curruchiche —the AG’s right hand— is also reportedly Kaqchikel.

The president-elect anticipated criticism: “We know that we have not reached the pluriculturalism that we would have wanted,” he said on Monday, promising to “continue to build better representation throughout our term on all levels of the administration.”

Exiled ex-Human Rights Ombudsman Jordán Rodas, who had Minister Roquel as his first deputy for five years —she is “a capable, and sensitive professional”, he said— also questioned the underrepresentation: “More Mayans are also qualified to be ministers,” he told El Faro English.

“But most important will be the kind of public policies to be implemented,” added Rodas, who was banned from running for VP last year, in a move that also struck from the race his ticket mate Thelma Cabrera, the only Mayan presidential candidate.

Nod to the business sector

The early controversy shows how the high expectations for the “new democratic springtime” Arévalo has promised are a double-edged sword. As president, he may find it harder to navigate the public debate if he is perceived to be trying —like he did during the campaign, and transition— to please all corners of a frustrated and polarized society.

Touching another nerve on the Left are two new ministers from the conservative business association CACIF: Infrastructure Minister Jazmín de la Vega, a former board member of the Chamber of Construction, will oversee over $840 million USD for public works, a hotbed for corruption and key to Arévalo’s pledge to rout out graft and patronage.

Energy Minister Anayté Guardado, ex-director of the Association of Generators of Renewable Energy of Guatemala, will oversee mining licenses, touching a core demand of many Indigenous leaders, to whom Arévalo promised a moratorium. In that former role, she sharply criticized local resistance to hydroelectric dam projects, which have often affected Indigenous communities and their ecosystems without proper consultation.

In his campaign, Arévalo repeatedly stressed his interest in broad national consensus and working with the private sector. More left-leaning Semilla candidates, like legislator Samuel Pérez, denounced the enormous historical influence of CACIF in politics, demanding “a future without CACIF”. Asked on Monday how this line squared with his cabinet, Arévalo fudged: “Some people may use it, but it was never a slogan of Semilla.”

CACIF remains a key player in Guatemala and appeared to play its own double-hand in recent months, defending the election results and expressing cautious optimism about Arévalo, while stopping short of calling for the AG’s resignation as she committed illegalities like the confiscation of sealed ballots.

“The ‘anti-CACIF’ narrative changed once Semilla won. Perhaps they now know that to govern it is better to build bridges,” wrote political analyst Juan Diego Godoy on X.

Former presidential candidate Thelma Cabrera, who is Mam Mayan, made the opposite criticism: “A future without CACIF. Lacking a compass,” she posted. The rural and Indigenous base of Cabrera’s party, the MLP, partly delivered Arévalo the presidency.

“Arévalo chose people for his cabinet who are part of the system, or not particularly adverse to it, perhaps with the exception of his finance and health ministers, who have been severely critical of it,” journalist Juan Luis Font told El Faro English.

“For Energy and Mining, he chose someone who not only was part of the hydroelectric business, but has obstinately defended it from criticism. He’ll soon need to show whether the ministry responds to investors in electricity or petroleum or to a complete society.”

“Nobody requested names for our cabinet, whether from [international] cooperation or the private sector,” said Arévalo on Monday.

Less surprising on his list were Jonathan Menkos, a close advisor to the president-elect and former head of the Central American Institute of Fiscal Studies, who will take on the Ministry of Finance; or veteran diplomat Carlos Ramiro Martínez, a vice-minister of foreign affairs who accompanied Arévalo in his meetings with the Puebla Group in Mexico, the Biden administration in Washington, and a recent tour through Central America.

A doctor in philosophy, Francisco Jiménez, will take his second turn as minister of governance, a role he held in 2009 under Álvaro Colom. Jiménez, also a professor of political science and public safety, will oversee the police — which makes it interesting that he worked for the Presidential Commission on Human Rights in 2019 and 2020.

Other ministers have technical backgrounds, like archaeologist and curator Liwy Grazioso, named Minister of Culture. Arévalo says the cabinet made an “unrestricted commitment to freedom of expression and the press” and to “transparency and honesty”.

Foes in Congress

On Sunday, Arévalo will take his oath at the Miguel Ángel Asturias National Theater, in Guatemala City, at 4pm ET, and address the country around 7:30 pm, in the Constitutional Plaza. At 9am that morning the new Congress will take office, in which Semilla will hold just 23 out of 160 seats and face enormous difficulties to form working majorities.

The largest incoming legislative bloc is that of the Vamos party, controlled by outgoing president Alejandro Giammattei, with 39 seats; followed by at least 27 legislators from the UNE, the party of Arévalo’s second-round opponent Sandra Torres, who five months after losing has still has not conceded the election.

In a public address after the cabinet announcement on Monday, Giammattei claimed there had been no coup effort in recent months, criticized the Constitutional Court (CC), which ruled in December that all elected officials should be sworn-in, and accused the U.S. and E.U. of coming to his house to threaten him unless he allowed Arévalo to take office. He also admitted to secretly having cancer last year, as widely speculated.

On Wednesday at 2:30 p.m. the OAS Permanent Council is scheduled to receive Giammattei in Washington, in what appears to be a golden diplomatic parachute for the president to leave office with honors despite his abysmally low popularity, his ties to multiple corruption cases —the prosecutors were forced into exile for investigating him— and remaining suspicion of his role in the attempts to overthrow Arévalo before he takes office.

Any last-gasp effort against the presidential duo —bogus criminal charges still stand against them— seems to rely on Shirley Rivera, the current president of Congress and a member of Giammattei’s party.

As a new trick, Rivera has announced that, in Sunday’s ceremony, she will unilaterally require certificates of probity timestamped in 2024 from each incoming legislator, despite the fact that they were vetted by electoral authorities in order to run and the Supreme Electoral Tribunal and CC ruled they should take office.

The high court rejected a similar requirement that Congress tried to impose on incoming legislators in 2020. But Rivera’s charade seems to point to the fact that if a new legislature is not formed, Arévalo would have no Executive Board to swear him in.

This article first appeared in the January 10 edition of the El Faro English newsletter. Subscribe here to tune into Central America.