On the afternoon of February 4th, the queues of Salvadorans in cars waiting to arrive at the Bethesda voting center blocked almost one kilometer of Maryland Route 355. Cumbia blared from the speakers of a Tesla X, its butterfly doors open to where three boys and girls had cranked up the volume to maximum. A blue t-shirt was draped over the hood, with the slogan “Nayib 2024” across the chest.

The sports car belonged to an immigration lawyer with a little over thirty years of experience, who paid for license plates with his name: Diego. Like many, he has no plan to return permanently to El Salvador. On his business card there is a photo of him flanked by the American flag, standing in front of a desk in a suit and tie. This Sunday his look was more reguetonero, more like the President whose re-election he had just voted for.

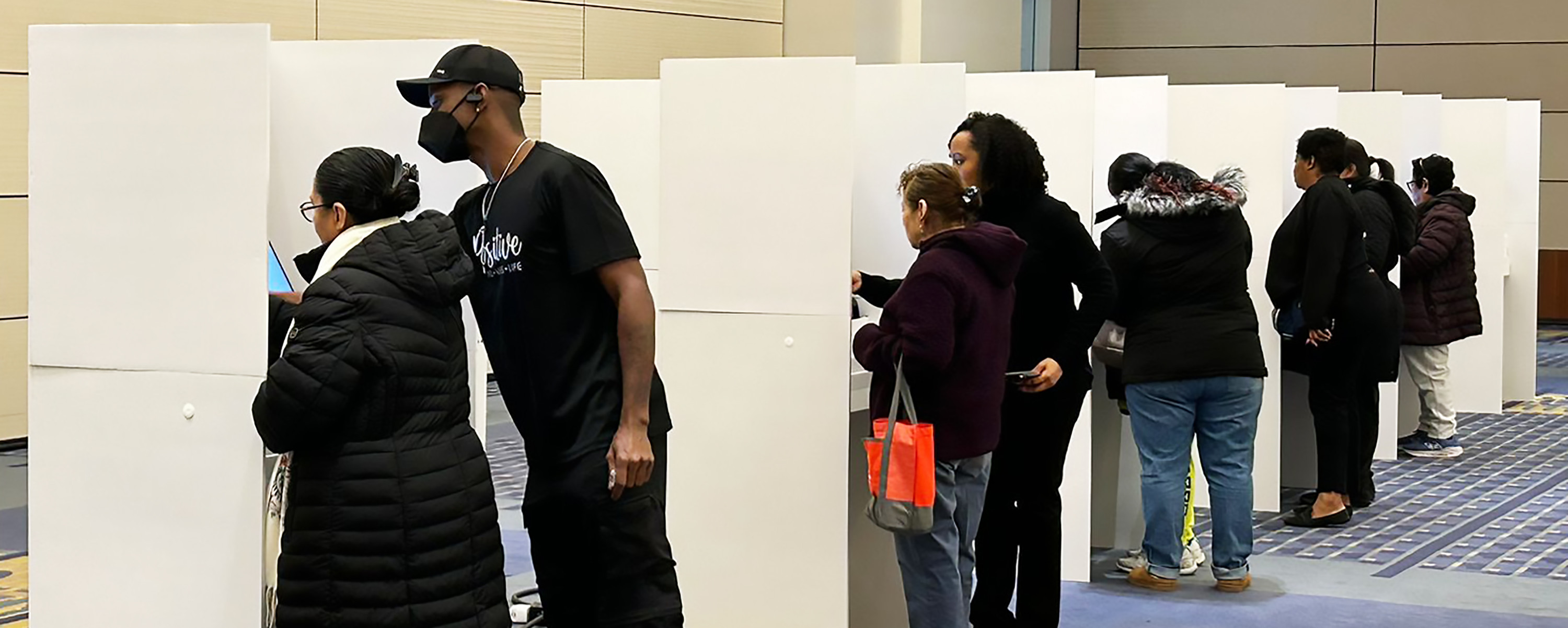

At the voting center’s main entrance, a volunteer from Bukele’s Nuevas Ideas party oversaw who could enter the building, and when. Inside, queues for the electronic voting booths lasted an hour and a half. The head of the center —the Supreme Electoral Tribunal’s (TSE) most senior authority present— limited herself to the menial task of directing those queuing to the correct table. The person responsible for inking fingers once people had voted was another Nuevas Ideas party volunteer, also wearing a cap with the logo and colors of the president-candidate.

* * *

By the week leading up to the February 4 elections, the government of Nayib Bukele had already pulverized the record number of Salvadorans voting abroad. In 2019, during the country’s previous presidential elections, 3,808 people voted. This time, by three days prior to the election, over 150,000 Salvadorans had done so, almost all in the U.S. To exercise their suffrage, they used the controversial system designed by the TSE at the President’s behest, which made it possible to vote from any cell phone or computer over the period of a month.

“You have to acknowledge the effort, because voting isn’t a big thing for most of our people here,” said Abel Núñez, a veteran immigration activist and current director of CARECEN in Washington three days before the election. “It’s not that it’s not important, but it’s not a priority for those living in the United States, who have other concerns to worry about”. Núñez, who arrived in 1979 as a teenager, knows how things were before the Bukele effect, and wondered about the after:

“The effort comes from the government, and from the Nuevas Ideas party, who put resources into securing this vote. It’s not from the Electoral Tribunal. The advertising has only come from one party,” he says. “It will be interesting to see if that continues, if these good numbers can be repeated in future elections or if it’s just because of their candidate. You must recognize that this isn’t coming from some kind of commitment to democracy or sense of citizen responsibility: It’s Bukele who is drawing people in.”

On Sunday Núñez was moved as he walked alongside snaking queues of Salvadorans in College Park, Maryland, people who waited up to five hours to vote: “If we could do this for elections in the United States, we would change how this country sees the Salvadoran community. And I think that the United States would look at Bukele differently, too,” he said.

He was referring to the historic lack of representation for Salvadorans, a community of hundreds of thousands of people in the Washington metropolitan area, who have no weight or voice and remain unrepresented beyond a few isolated individuals. These individuals are usually second-generation migrants born in the United States and are unable to mobilize the diaspora vote for local elections.

Jessy Mejía was born in El Salvador, but has cut a lone path as a leader. She is part of the team around Marc Elrich, Montgomery County Executive, and provides him with a link to the Latino community. She previously worked for the Maryland governor for seven years. On Sunday she met with Núñez, as he drifted sleepily between queues of voters:

“Imagine this in a local election, or a national one?” he asked, in a tone of unmasked euphoria.

“That’s what I’ve been telling people here: Okay, all the Salvadorans are present, but please, come out to vote in the elections here,” Mejía agrees.

“Imagine this in a county election…”

“Oh my god, we would take them over! If there was this level of commitment at a local level, or national… forget it! We would turn the tables here in the United States.”

Núñez says that the United States still sees Salvadorans as workers, as a cheap labor force with a good reputation, but politically they are overlooked. “They’ve given us access to the country, but no influence… But if politicians could see this, they’d be afraid,” he said on Sunday. “Our work in organizations would be so, so easy. We could tell the mayor of Washington: ‘look, if you don’t do x or y, you’re gone.’ The image of these queues could be so powerful. But the sad thing is, I don’t know how much real influence this is going to give us over the government of El Salvador, either.”

* * *

From the beginning of his political career, Bukele spotted an opportunity in the scorn that Arena and the FMLN always showed for the diaspora vote. His party, Nuevas Ideas, was born in Washington, financed by a handful of successful immigrants who spent years wanting to be listened to in San Salvador. Now that the president no longer needs their money, he has broken with many of them, but not before taking over part of the FMLN’s structure in the United States. For years, he’s been careful to hold onto this political asset. Despite the lack of census data, it is estimated that there are over three million Salvadorans in the United States. In support of Bukele’s unconstitutional re-election, the Executive Branch flexed its muscles to the tune of around 900,000 newly registered voters. In the end, more than 330,000 people cast ballots abroad.

The registrations resulted from huge logistical efforts involving the country’s entire foreign service. Millions were invested, from public money. For Bukele, the righteous avenger who boasts of a baptism of fire, for politics and on the streets, he is all the cleaner for having the blessing of El Salvador’s “purest”: those who fled violence and hunger and remained untarnished by the country’s reviled post-war politics. Moreover, it is they who sustain Salvadorans who stayed in the country with generous remittances.

These elections saw other parties also attempt, less successfully, to renew themselves through the diaspora, and all with less resources than Bukele. Two presidential candidates from the opposition made something of themselves in the United States: Joel Sánchez, of Arena, is a businessman based in Dallas. Luis Parada, who dreamed of being the face of a united opposition but ended up only on the ticket of the small party Nuestro Tiempo, has for decades lived and worked as a lawyer in Virginia. It is revealing that neither of the two have even shown an interest in directing part of their campaign toward the immigrant community. Not one meeting, not one policy, nothing.

In Bukele’s case, on February 4 he was not only seeking a narrative boost. An injection of some hundreds of thousands of extra votes, and the mobilization of an enormous demographic, has a significant impact on a census as small as El Salvador’s, a country with under 7 million inhabitants. In recent years, the emigrant vote has become a reason of state.

One diplomat explains that the ambassador to the United States, Milena Mayorga, has acted “more like a consul-general,” dedicating attention and drawing in the community abroad, “than as an interlocutor with the Biden administration.” The bombardment of government propaganda, directed at a Latino audience through radio and online platforms, is another constant in key states. Since over a year ago, huge illuminated letters can be seen when leaving the San Salvador airport, vindicating migrant pride through the hashtag #DiasporaSV.

State functionaries and politicians now make constant trips to circulate among Salvadoran communities abroad. Last September, Ernesto Castro, president of the Assembly and one of Bukele’s closest confidants, led an enormous congregation in an Evangelical church in Virginia. He was accompanied by 16 other Nuevas Ideas legislators who sat alongside him for the event, but remained silent for a two hour-long uninterrupted speech from Castro.

His rally, which attracted 500 people —1200 were expected but there was rain— was a virulent attack on previous governments, against the oligarchy, against journalists and human rights defenders. The most lively applause of the night could be heard when he referred to opposition parties as “sons of bitches”, and when, following a long video on gang violence which included explicit images of decapitations with machetes, Castro defended the state of exception. “Give them a death sentence!” shouted someone in the crowd.

Equally significant are the words spoken by the master of ceremonies at the start of the event: “We have a president who has turned El Salvador into an exemplary country,” he said. “It’s an honor, now, to identify as a Salvadoran. He is bringing dignity to us Salvadorans living abroad.”

After the meeting, in the parking lot, among dozens of mid-range family cars was a Ferrari Testarossa, a symbol of luxury and sophistication in the 1980s. A few meters away, one of the assistants could be seen heading home in a four-axle cargo truck.

Trauma Politics

Carlos Escamilla is 55 years old, with the appearance of someone well over 60. He has lived in Langley Park since he was 20, and has just joined the queue to vote in College Park when I remind him that he is facing a four hour wait. “We haven’t been waiting hours, we’ve been waiting a whole lifetime,” he replies.

He was recruited to the army aged 15, and came to the United States for the first time as a refugee in 1989. He was denied asylum. The following years in El Salvador were years of poverty. “Those of us who fought a war — what did we win?” he says. “That aid that came to help war veterans, what did the leaders do with that money? Or the earthquake aid. How many earthquakes have there been and they gave people sheets instead of building them houses, despite the millions given by Taiwan? Look, I’m not a politician, but I can see how things are!”

He feels forgotten. He complains that now there are people who migrate with a work permit and he’s been undocumented for two decades. Unable to find employment for the past month, he knows that at his age it’s going to get harder. He paraphrases from the Bible and takes refuge in faith. And he explains that that’s what he has in Nayib Bukele: faith.

“I always had hope in my country. It was the people who governed it who I had no faith in,” he makes clear. “I never knew the life of a teenager. All I knew was shooting guns, but we all came to realize that in our country both the left and the right have been ruined. I can see that the man is no atheist. Look, I don’t know him, but my town, Huizúcar, is a few kilometers from where Bukele was mayor, and the people in the surroundings watched it progress, and you know that when there’s progress something is going right, a man with a bad conscience can’t make good in a place.”

A few hours before, in another voting center in central Washington, a woman called Guadalupe put forth a similar argument. She was born in Cojutepeque and has lived for thirty years in the neighborhood of Columbia Heights, home to many Salvadorans in the U.S. capital. She left just after the war because of a lack of work. On Sunday she wore a t-shirt emblazoned with a picture of Nayib Bukele praying on the day, four years ago, that he used the army to take over the Legislative Assembly.

“When I was in El Salvador I did vote,” she tells me. “Maybe not in the right way, maybe motivated by fanaticism. One isn’t always well-informed, but you vote anyway”.

Those politicians failed, and now the country is finally rising up. That’s why she calls it “a privilege and an honor” to be allowed to vote for the first time in the United States. She is surprised when I tell her that’s not how it works; fifteen years ago she could have done it legally. No-one told her. She didn’t know. It’s evident that the governments and political parties at the time had no interest in her knowing.

“What do you think of the criticism of Bukele for…?”

She interrupts the question to say: “People can criticize, right? The difference nowadays is that everyone knows that the facts are there. They’re not lies: Our family is safe, they can go out in the streets and nothing will happen. Parents with their children, children with their parents, grandparents, nieces and nephews, siblings, grandchildren.”

A few days ago the renowned Argentinian journalist Martín Caparrós coined the term “efficientocracy” for the government model which diverts from democratic norms but offers visible results. This mode has a distinct reach among the diaspora because, as Abel Núñez, the director of CARECEN, explains, from the United States “people see results but they don’t live the consequences in the same way.”

In the context of pain, and the memory of it, voting for Nayib Bukele makes sense for millions of Salvadorans. Each individual finds their reason and, if they have them, they contain their doubts.

Germán turned up on Sunday to vote in the center installed in a hotel in Bethesda, a wealthy area of Maryland to the northeast of Washington. Having seen me taking photos he began to shout “N for Nayib!” He is from Intipucá and returned yesterday from 15 days in El Salvador. It had been 22 years without visiting the country. His brother travelled with him, visiting for the first time in 30 years.

He says he found the place finally changed. “Well, safety has changed. Rural places will always be poor. You can still see the poverty,” he notes.

It was enough to motivate him to vote. Before, it seemed to him like a very difficult process, and he didn’t think it gave him “any certainty of change”. Next to him is Norma, his wife, who threw her passport in the trash years ago. “I felt disillusioned with the country. I came here in wartime, I became a citizen over the years and I didn’t want to hear about any of it. I decided I’d never go back,” she says. That’s why she was unable to vote on Sunday. If she could have, she would have voted for Bukele.

Ana and Sandra, Norma’s sisters, migrated just two years ago. Sandra has a 19 year old son and grew tired of keeping him inside for fear he would be killed. One of her nieces was taken by gang members when she was 18 and her body was never recovered. “Look, no-one understands the other’s point of view until they’re in their shoes”, she replies in response to questioning of the president’s methods. She criticizes previous governments, who negotiated with the murderers.

When I tell her there is proof that Nayib Bukele also negotiated in secret with gangs, her gesture distorts, but she looks at me with sadness in her eyes as if wanting me to understand: “Look, if there is no other path apart from negotiating with them, because there’s no other way, okay let’s negotiate but let’s do it well, not like the others who even did that badly — we never got any peace in return. Let’s negotiate so that they let people breathe, so they’re not killing innocent people for the fun of it. And I know they were innocent people because they were people I loved.”

As in the 70s and 80s, for many Salvadorans pain has become the new dividing line. Your side depends on who relieves it, and who causes it. Víctor Rodríguez, “el Crack”, is a 40 year old conceptual artist who went into exile in September 2022. He had an exchange on Facebook with the director of the government’s Social Fabric unit, Carlos Marroquín, after he found out that he negotiated with the gangs, and a few nights later someone set Crack’s car on fire. He is now in the process of seeking political asylum.

On Sunday he voted in central Washington, in the same place that Guadalupe lets herself dream. He voted for the FMLN.

“Vote for different sons of bitches, you cerotes, losers. Do something, losers. Ask questions, ask some fucking questions,” he says in one of his recent social media videos. “We weren’t worth shit these past five years. And before as well; that son of a bitch didn’t want us to have any debates, and now you’re all playing dumb. Stop bullshitting, eat shit, go out and vote, losers”.

I ask him how much of the cursing in those videos is performance, the vulgar personality he seems to have created for his activism from exile. In the 2014 Presidential elections, which after the disappointing and corrupt government of Mauricio Funes, handed a second mandate to his party of former guerrillas, Rodríguez ate his voting ballot in front of television cameras and dozens of people who were waiting at the electoral college, including authorities from the Supreme Electoral Tribunal. After his allegorical performance about hunger for power —“it was the pupusa revuelta with hunger and democracy,” he jokes— some wanted him to face charges for destruction of electoral material. Five years later, in the elections where Bukele was victorious, he turned up to vote dressed in all-white prisoner garb, carried inside a coffin.

“This time I had to vote, I had to do something with my mini-vote which is worthless,” he says. He defends the insults in his messages as provocations, and a way of searching, in some senses desperately: “Bad language is the language that connects with our people. The way I see it, sometimes it’s only when they’re cursing you that you feel empathy. Every tool interests me, communication in every hue, and I’ve seen that if you’re calm, diplomatic, they don’t listen to you. Cussing each other out is the way!”

Now he survives in any way he can. He has legal support from the international organization Artistic Freedom Initiative, and scrapes together a living doing small jobs washing yachts, selling Mexican food, doing maintenance work, or pulling up floors. He says it’s a relief to him, at least, that his mother is less worried with him abroad. Beyond that, like the thousands for whom the peaceful El Salvador of Bukele means fear, or who are punished for expressing themselves in public, everything is a frustration.

“After this Sunday the rules of the game are going to change, and if people don’t realize it quickly, later you’re not going to be able to do much about it,” he says. “But I feel like the game isn’t over yet. For the general population a period of fear is coming, but after so much confidence in politics we have to accept that it will require putting yourself on the line. Hunger and corruption are there, and all this won’t be sustainable. The moment will come when we Salvadorans react,” he says. “The moment of the cerotes!” he laughs.

It’s a bitter laugh. Then, exile creeps back into his expression. “My intention was always to wake someone up, for people to participate more…” and he pauses. “Now, it hurts that people told me ‘go on, eat the ballot’ and they did nothing.”

While a few meters away people continue to vote, and a family in the uniform of the president’s t-shirts take photos, something unravels in Rodríguez and he cries in silence for a few minutes. “So much, for nothing,” he laments. And as if suddenly seeing an opportunity for performance, he declines the paper tissue I offer him, almost smiles, and dries his tears with the open pages of his passport.

A Controlled Election

Minutes prior to Crack’s arrival at the voting center, a youtuber in metalhead attire doing a livestream strolls in, asking “Everything in order? None of the 3 percent have come in causing problems?”

The 3 percent, or the 4, or “the same ones as always” is how Nayib Bukele refers to anyone who questions him since coming to power, or who doesn’t cheer him on in the polls. In 2019 he won the presidency with 53% of the 51% of eligible Salvadorans who turned out to vote, but from the first moment he reinterpreted his popularity rating to say that he had the backing of 97 percent of the population. Sunday’s election, for him, was a referendum to demonstrate that.

Eight months ago the Legislative Assembly, under the president’s control, passed a law to reduce the number of members of congress, and changed the mathematical recount system and the assignment of seats from the Hare quotient to the D’Hondt, which favors parties with more votes and diminishes the representation of the minority. It was not about winning the presidency or not, but ratifying a message of absolute power and, above all, it was about getting the opposition out of congress. “Every Nuevas Ideas seat we lose is a seat lost to the gangs,” was what the head of the ruling-party legislative bloc, Christian Guevara, tweeted for the entire week leading up to the vote.

The diaspora vote was key to Bukele’s strategy. That is why the Special Voting Law for Voting Abroad, which Bukele designed, assigns all the votes of those who have their residency registered abroad to San Salvador, which has the largest share of seats. It’s why throughout January Nuevas Ideas put up tables on streets and in shopping centers in specific neighborhoods in the United States to help people vote online — known as the “cyan points”, the party’s color. And that’s why on Sunday, the only day that diaspora voters who still had an address in El Salvador could vote, they did so in person, using electronic urns. The governmental machine —the Nuevas Ideas machine— took control of the process to the point of eliminating, in some places, the Supreme Electoral Tribunal’s authority.

This was anticipated on Friday, February 2, in an investigation in the online magazine Focos, revealing that the Bukele’s Chief of Staff, Carolina Recinos, gave orders to dozens of heads of voting centers in the United States who belonged to Nuevas Ideas, despite the fact that these positions are in theory non-party aligned. The orders included coordinating with the cyan points which would be installed throughout the day inside the voting centers.

Beforehand, the Supreme Electoral Tribunal had rejected the list of names that opposition parties presented to be part of the Polling Stations, leaving them in the hands of the governing party and its allies. This is all to say nothing of the absence of an independent audit of the IT system for online voting. On Saturday Elsa Mendoza, director of International Affairs for COENA, the high council of Arena and the party’s top authority for the vote in the United States, told me from New York: “We’re going into these elections disarmed”.

* * *

Voting day on Sunday, February 4, was brazen.

In the Washington D.C. Convention Center the Nuevas Ideas electoral observers put pressure on the head of the center to expel journalists from the room where voting was taking place, and instead of an official from the Supreme Electoral Tribunal responding to reporters’ questions, they replied themselves. It went exactly as planned in the virtual meeting with Carolina Recinos; the cyan points were present in every center, this time without colors but attended to by consulate staff who are employed directly by Bukele. They were accredited by the TSE and used, according to them, tablets belonging to the Tribunal. Their job was to help those who didn’t know how to, or hadn’t been able to, vote online.

In their effort to get every vote, the Silver Spring consulate opened on Sunday so that anyone who hadn’t been able to collect their government ID card, or who hadn’t wanted to before, could do so on voting day.

Even so, in most centers there were problems with the IT system which did not recognize certain ID numbers or, even more frequently, passports. In Washington or in Bethesda some were unable to vote after three hours waiting, while technicians and TSE staff made up explanations. “There is no clear pattern, it’s random, there are some document numbers that the system isn’t recognizing,” said the Tribunal representative at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center, in the center of the capital. “I have already notified the Tribunal in San Salvador and they have informed me that these people will be unable to vote.”

It did not play out like this in every case. El Faro obtained a copy of a video in which two voters attending the Marriott at LaGuardia airport in New York explained that their documents did not show up as registered. However they say that after a phone call, TSE staff entered them into the system at that moment in order to be able to vote.

A similar video, recorded by an electoral observer at the College Park voting center, shows Ambassador Mayorga speaking on the phone in an attempt to resolve this same problem for a number of voters whose passport wasn’t appearing in the system. At one point in the recording she is heard saying: “They want to vote with their passports, but the system can’t find them… Yes, because there are quite a few of them”. A little while later, she gives one of the contractors in charge of document digitization the direct instruction to “send a photo of all [the unregistered documents] so that the Supreme Electoral Tribunal could see the impact and correct it.” When the electoral observer complains to the ambassador that she is carrying out a role that is the responsibility of the JRV voting station, Mayorga replies that she is in the center “as an observer” and continues giving instructions to the voting center staff.

The race to reach the biggest number of votes possible within the United States grew increasingly complicated as 5pm, when voting would close, drew closer. In Bethesda, a JRV member worked intensely to guarantee that the IT system didn’t block automatically at 5:30pm and to confirm that the employees at INDRA, the business responsible for electronic voting, would pay them overtime to continue to work until everyone in the queue had voted. A FMLN observer has complained that in the Walter E. Washington center, in the capital, Nuevas Ideas representatives ordered for the doors to be reopened past 5:20pm so that eight people who had arrived late could vote.

By 5, in College Park with its endless queues, around 4,000 people had voted. But hundreds were left queueing in the street. There were arguments over whether everyone should be allowed to enter or not, worsened by the fact that the rental contract for the premises meant it had to be handed over, empty and clean, at 9pm. The possibility of extending the contract was considered. The center finally closed later than 6:30 and around 300 people were left outside. There were protests. The University of Maryland campus police, where the center was located, arrived to intervene.

Meanwhile, the recount fed the chaos in San Salvador. Hours went by and there was still no official data. There was not even any way to establish levels of voter participation. Once again, the Supreme Electoral Tribunal adhered to the government agenda, considering the question of voters in the United States to be a priority. The same night, it was announced that voting would be reopened for them. The Attorney General himself made a statement on the topic: “My Office will charge anyone who has committed a crime,” he tweeted. “All voters who were waiting, and who arrived before closing time, should be allowed to vote.”

On Wednesday the TSE finally changed course, and ruled out the possibility of reopening the vote, from which there are still no official results. Despite the lack of a final tally, Bukele has already proclaimed himself victorious. To celebrate this strange voting in stoppage time, which is explicitly prohibited in electoral law, Sunday, February 18, was chosen as a date. It was announced by a TSE magistrate on Tuesday afternoon, and this is how Elsa Mendoza, Arena supporter and party head of voting abroad, found out.

The official party had the date long before. Just after 7am that Tuesday, still 6am in San Salvador, a Nuevas Ideas party official in Washington sent me this message:

“Good morning, mister. Groups are being put together for the 18th of this month. When there is information about the locations, I will let you know. Good day.”