El Faro English shines a light on Central America. Subscribe to our newsletter.

New video footage published last night by InSight Crime and Univision, secretly recorded in 2013 from a drug trafficker’s wrist watch camera, reveals members of the Honduran cartel Los Cachiros offering $650,000 dollars to Carlos Zelaya, brother-in-law of now-president Xiomara Castro, for her presidential campaign that year.

In the videos, the traffickers also spoke of bribes they had paid in the past to Manuel “Mel” Zelaya, husband and strongman of the Castro administration as well as founding secretary-general in 2011 of the current ruling party, Libre. The video also shows Carlos and Cachiro trafficker Devis Rivera Maradiaga negotiating the rental of campaign vehicles.

“Half must be for the comandante,” Carlos Zelaya says in the video of the campaign money under discussion, using a common party nickname for his brother Manuel. “He and I will share the other half.” Speakers repeatedly mentioned “Mel” and “Carlón,” the Zelaya brothers’ other public nicknames.

These reports add damning evidence to drug traffickers’ multiple courtroom testimonies accusing Manuel and Carlos Zelaya of having past campaign ties to drug traffickers. In her most recent 2021 campaign, Castro promised to pursue drug operators and usher in a return to democracy after years of “narco-dictatorship”, referring to her disgraced predecessor, Juan Orlando Hernández, whom she extradited to the United States.

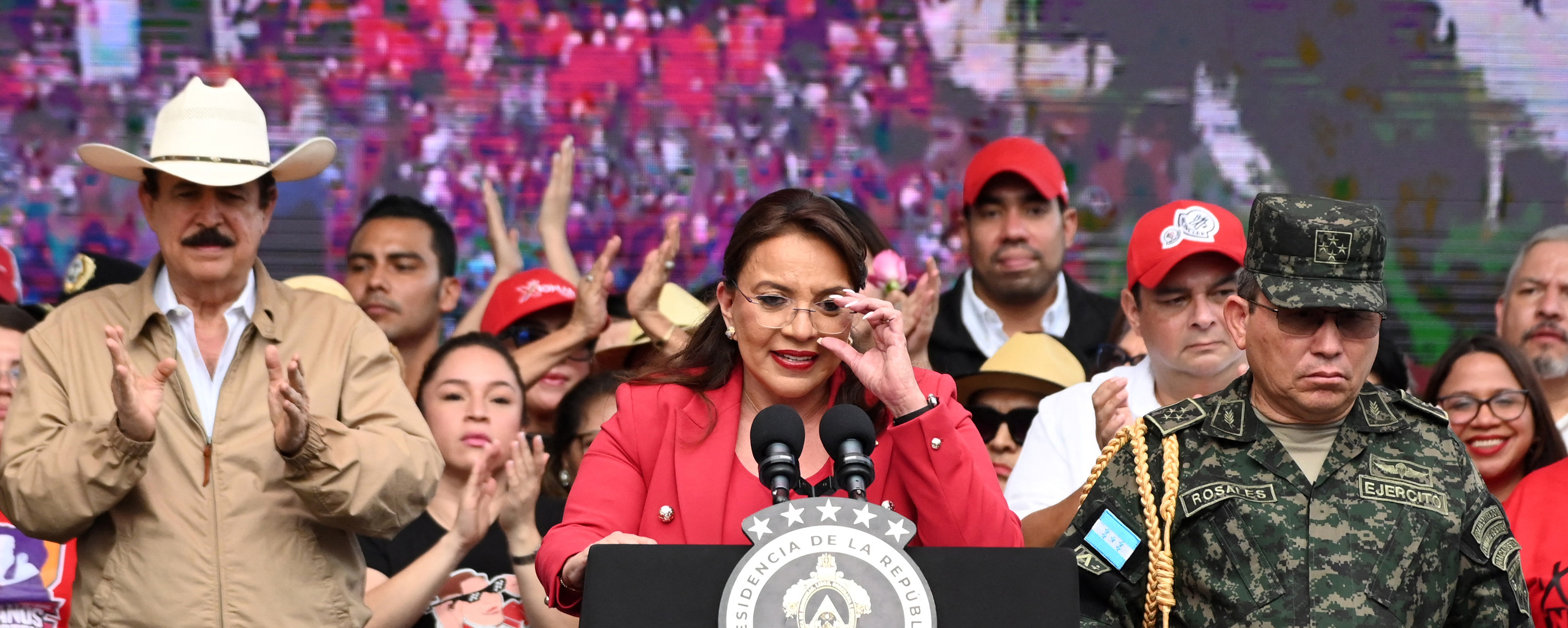

“I condemn every type of negotiation between drug traffickers and politicians,” Castro stated in a national broadcast without broaching the specific allegations, before immediately leveling accusations of foreign intervention against the U.S. Embassy.

“The plan to destroy my democratic socialist government and the upcoming electoral process is underway,” the president continued. “The same dark internal and external forces of [the] 2009 [coup] are reorganizing in our country, with the complicity of national and international media, to deal a new coup d’état that the people must repel.”

This is not a new accusation: Since the Castro-Zelaya family’s return to the presidency in 2021, they have consistently branded critics, non-aligned press, the political opposition, and anti-corruption advocates as coup-mongers.

“Agents of the Embassy, activate. You make me sick!” wrote Libre legislator Scherly Arriaga on Tuesday night, the war of narratives in Honduras in full swing.

Opposition groups were quick to take their own jabs. “Mel is right, JOH [Juan Orlando Hernández] was only the head,” quipped Jorge Cálix, a presidential pre-candidate for the Liberal Party. Cálix defected from the ruling Libre party this year as the result of a longstanding and acrimonious rift in Castro’s legislative bloc. “The narco-dictatorship is still there, and we have to remove it,” he added.

Juan Orlando Hernández’s wife Ana García de Hernández, who has announced she will run for president in the National Party primary in March, seized the revelations to dramatically declare, while providing no exonerating evidence for her husband, that “today time has vindicated us… Juan Orlando Hernández is innocent. He will return.”

Hernández’s watershed trial this March in New York ended in his sentencing to 45 years in prison as the judge called him a “two-faced politician hungry for power.” It also painted a damning picture of the entire Honduran political class’ ties to traffickers as witnesses said they paid bribes to all three major parties, including to Carlos Zelaya, a close operative of Castro and Manuel Zelaya and, until last weekend, secretary of Congress.

In a February interview published by El Faro English, Fabio Lobo, a key witness of the trial, accused Carlos Zelaya of running a drug airstrip before 2010. From the stand Lobo also provided unflinching testimony against his own father, former president Pepe Lobo. Another witness against Hernández had stated in a previous trial that he, too, paid bribes to Manuel Zelaya in the latter’s 2005 presidential campaign.

Extradition woes

The Tuesday revelations increase the relevance of Castro’s announcement on August 28 that she will seek to end Honduras’ U.S. extradition treaty. According to InSight Crime, the Castro administration made the announcement after the reporters had spoken with one of the participants in the 2013 meeting.

“Drug traffickers are an essential factor in reaching elected office because they put money on the table — not only for the electoral campaigns, but also to buy votes in Congress and place people in positions of interest for drug traffickers,” constitutional lawyer Joaquín Mejía told El Faro English. “To date no high-ranking military leaders have been extradited. Only members of the Police, politicians, officials, and business people.”

“Instead of demilitarizing the state, Castro has given the military more power, without a purge or process of accountability for the crimes of the past and their ties to drug trafficking,” he continued. “While the existence of a coup effort cannot be discarded, the alleged ties of members of her family and party to traffickers have been revealed, too.”

Further trying to head off the video footage, Carlos Zelaya and Defense Minister José Manuel Zelaya, Castro’s nephew, resigned on August 31. The former said that he would submit himself to criminal investigation in Honduras for a meeting with drug traffickers in 2013 to “speak about an offer of a campaign donation,” but denied ever receiving any money and claiming that he acted unilaterally, without Castro’s knowledge.

The Castro government has claimed that it denounced the extradition treaty after U.S. Ambassador Laura Dogu criticized a meeting between the defense minister and Venezuelan defense chief Vladimir Padrino, who was indicted in the US in 2020 on drug charges. It is Castro’s sharpest public allegation in three years against the Biden administration of violating Honduran sovereignty, a pillar of her foreign policy rhetoric.

The president did not explain what the diplomatic relationship with Venezuela —her administration was among the first to claim that Nicolás Maduro had won the election, alongside Cuba, even as Venezuelan electoral authorities refused to release ballot counts— has to do with extraditions to the United States. Under the current framework, extraditions are requested through the Honduran Foreign Ministry.

“I will not permit the extradition treaty with the United States to be instrumentalized to disarticulate the armed forces, topple my government, and destroy the elections,” Castro said in the national broadcast.

“The denunciation of the extradition treaty had nothing to do with national sovereignty,” says Mejía. “Now the government is using the same arguments as Juan Orlando Hernández: that this is political persecution from the United States.”

“This shows the profound need for structural political change in Honduras,” he adds. “What we saw in the Hernández trial was the tip of the iceberg. Now we’re seeing how drug trafficking has infested the entire political class.”

“The party in power perceives that they could lose the elections, and it is in their interest to produce instability, which weakens institutions, instills fear in the population, and produces polarization,” Lester Ramírez, coordinator of the Association for a Just Society (ASJ), says of the extradition scandal. “This is part of a strategy to create chaos that they control. Juan Orlando did that, and this government is, too.”

In the last week and recent months, El Faro English has requested multiple interviews with Honduran Foreign Minister Enrique Reina, a leading spokesperson for the administration, but he has not granted one.

Upcoming elections

The Honduras-U.S. extradition treaty allowed for former President Juan Orlando Hernández to be removed to New York in 2022, in the first days of the Castro administration, as both a clear early gesture of bilateral cooperation and as an implicit nod to the weakness of the Honduran courts and prosecutor’s office.

The Honduran Public Prosecutor’s Office is now led by Attorney General Johel Zelaya, a former Libre municipal candidate who was confirmed after political violence and months of congressional gridlock, and in spite of rules against party affiliation.

The State Department has stated that the treaty is still legally in effect, but urged Castro to backpedal, adding that the decision “will harm the efforts of Honduras and the United States to jointly fight against drug trafficking and bring criminals to justice.”

“I have very little doubt that Mel and others had this [extradition treaty] in the back of their mind for some time,” asserts a diplomat in Tegucigalpa who spoke anonymously, citing diplomatic press restrictions and the threat of government retaliation. “Libre has spent years railing against the ‘narco-dictatorship,’” the diplomat added. “The irony will not be lost on the public. I think it will be a major blow to their electoral prospects.”

Castro has appointed her party candidate Rixi Moncada as the next minister of defense, just hours after Moncada had formally announced her presidential bid. The Defense Ministry oversees the Armed Forces, the only military in Latin America legally tasked with safeguarding their country’s electoral process, which will be held on Nov. 30, 2025.

“She [Moncada] has a strong personality and is in Mel Zelaya’s circle of trust. With the rumors of a coup d’etat, a profile like that is necessary,” says Mejía. “While juridically she has no obstacle to participate [in the elections], in ethical and political terms it raises a lot of suspicion. Obviously this places candidates from other parties, and even from her own, at a disadvantage. This takes away credibility from the Honduran electoral process.”

In the last year, the Castro government has intensified its lashing-out at perceived critics, stoking a climate of fear among civil society organizations and uncertainty about the administration’s political intentions.

“This is very worrying,” said the diplomat of Moncada’s selection as minister. “She would be legally required to step down by May 2025, six months prior to the November election. If she does not do so, this would be the making of a crisis.”

This article appeared in the September 4 edition of the El Faro English newsletter. Subscribe here.