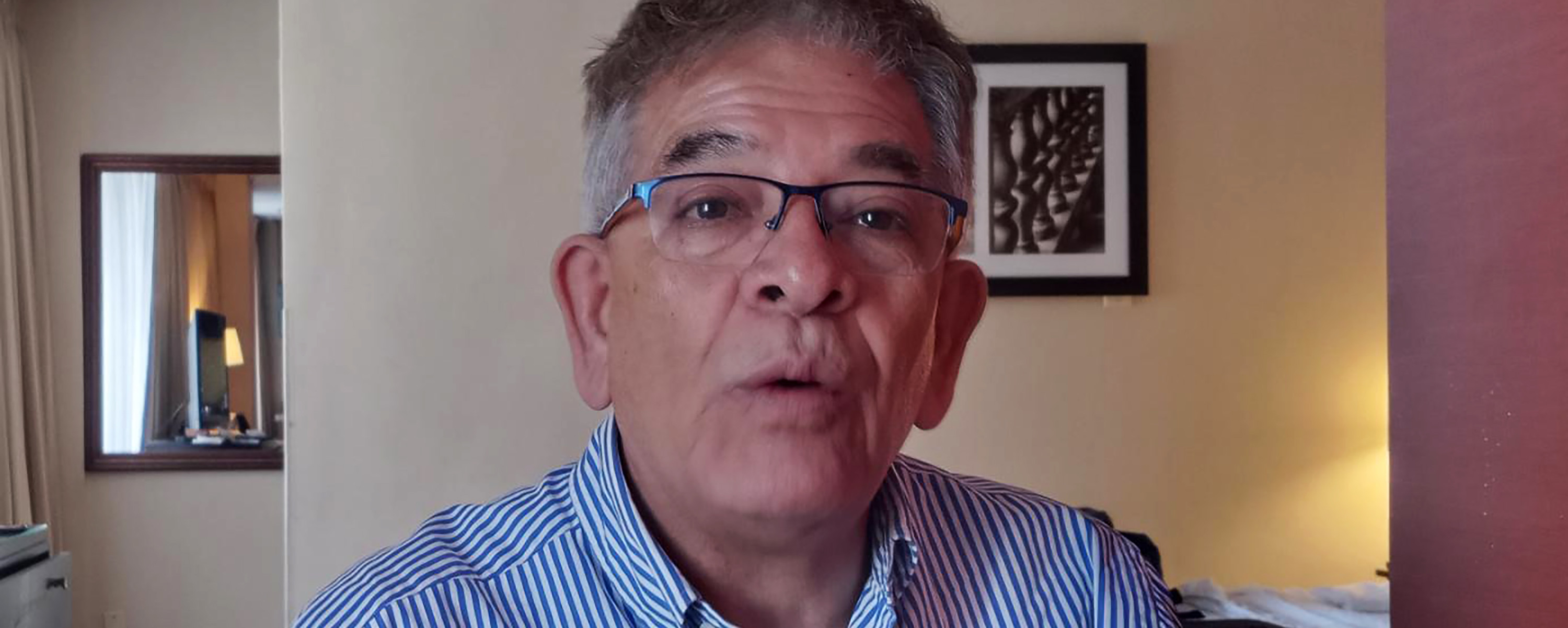

Since November, Miguel Ángel Gálvez has been living out of a suitcase. In the hotel room that serves as his home for the week, the coffee pot has been placed on the floor, next to the bed, to make more workspace on the desk. When I arrive for our interview, he shuffles a stack of papers and moves them from the small table to improvise a place for us to talk. This is what exile has meant for him: always improvising, always adapting. And always keeping busy. He spends nearly every day denouncing persecution against him and his fellow judges. Nearly every day, he breaks down while talking about his and his country’s plight.

Prior to his exile last November, Gálvez, 64, was the judge of the historic “Death Squad Dossier” enforced disappearance case. In his career he also sent former Guatemalan dictator Efraín Ríos Montt to trial for genocide, imprisoned ex-President Otto Pérez Molina on charges of corruption, and handled a major government corruption case implicating banks, construction companies, and the media. He was preparing to retire when he found himself in the judicial crosshairs of the very apparatus of corruption he had been attempting to dismantle and was forced to flee the country. By then, the daughter of Ríos Montt, Zury Ríos, was leading the polls in her bid to become president of Guatemala.

Gálvez speaks about the situation plainly and with unmediated dignity, without hiding his pain or holding back his vulnerability. “Exile hits so hard because you’re already experiencing it even before you leave,” he says. “It’s like if a doctor tells you what day you’re going to die. There are times when you start to think that maybe it was a mistake to believe in the justice system at all.”

He blames his departure on a diffuse “them,” encompassing the current government, the private interests that supports it, its enablers in the justice system, and above all, the military, which he says has once again taken control of the country’s institutions to procure impunity. For ordering military officers to trial, “they” have forced him to flee his country, Gálvez says. On March 20, speaking before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, he warned the Guatemalan representatives: “I hold you responsible for anything that happens to me, not only to my own wellbeing, but also to the wellbeing and safety of my family in Guatemala.”

Two weeks ago, Gálvez came to Washington, D.C., to testify in person before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and meet with U.S. officials. Gálvez says that those meetings made clear that the United States has no interest in taking tougher actions against the officials who are turning the country into a kingdom of impunity and corruption: “The U.S. already has so few allies in Central America, and they don’t want to lose Guatemala.”

You continue to appeal to international bodies and denounce your persecution, but I assume you don’t have any intentions of returning to Guatemala?

When the permanence of the CICIG [the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala] was still an open question, we were in an arm-wrestling match, and now that they’ve won, the judiciary has totally deteriorated. They no longer respect the law. The current magistrates are acting foolishly…. The dismantling of the rule of law has been incredible to witness. So, yes, under these conditions, I know I won’t be returning to the judiciary. Things have deteriorated so much... Just imagine this: one day, I was in a packed courtroom when suddenly [Ricardo] Méndez Ruíz and [Raúl] Falla [attorneys for the Foundation Against Terrorism, or FCT, a group of far-right operatives with ties to military] stuck their heads through the door, and shouted “jueeeez prevaricadoooor!” (“crooked judge!”), in the middle of the hearing! Everything is falling apart. The justice system in Guatemala has completely collapsed. Completely.

What you’re describing sounds like schoolyard bullying.

Exactly. There’s such complete insolence and immaturity, so much cynicism, you would think that even these bullies might have some principles, some ethics. But no, this is the situation. These are the people in power now. To me, that’s the issue.

Look, before this all happened, I was planning on just finishing up a few cases and then retiring. I was going to ask Rafael Landívar University, where I was teaching at the time, to give me a few more classes, and with my pension and the courses, I thought, “I can make up the income and live in peace.” But they didn’t give me enough time.

What cases were you hoping to wrap up?

The Cooptation of the State corruption case, the Diario Militar trial [Death Squad Dossier]... There were some very interesting and important cases, at different levels, like one pre-trial hearing against a judge in Izabal related to drug trafficking. I thought, if I set my mind to it, I can finish those cases in a year, or a year and a half, and then I can retire in peace.

What made you decide you had to leave?

I mean, I’ve had bodyguards since 2000. I was one of the first judges in Guatemala to be assigned a security detail. And in 2015 they gave me an armored vehicle. I always knew I was at higher risk than other judges, who all take on some level of risk. But then last year, there was a point when it became too great and I couldn’t stay any longer. Ever since Méndez Ruiz threatened me in May, there was an intense campaign of harassment unleashed against me. They even started to follow me, break into my home... They threaten me with total impunity. And then the risk experts did an analysis, taking into account all the cases I’ve brought against the military, and all the corruption cases, and they told me that they couldn’t rule out the possibility of an attempt on my life. A kind of countdown began, a countdown to a moment that was coming, coming, coming... and then would one day arrive. Why? Because in Guatemala, the institutions of state are being militarized, the Ministry of Governance especially. They’re restructuring it to be like it was in the 80s, when each department had a military officer. From studying the Diario Militar case, I understood exactly what was going on.

What do you mean by that?

That Guatemala is designed for impunity. Romeo Lucas governed from 1978 to 1982; Efraín Ríos Montt forced him out with a coup and governs from ‘82 to ‘83; in 1983 Ríos Montt was forced out by a coup and Mejía Víctores took the presidency, then called for a constituent assembly. But how can you justify, in the middle of a constituent assembly, with all the pressures to sign a peace agreement, during years when the guerrilla groups and the government are sitting down to dialogue, that they continue killing professionals and students? What could justify the continued dismantling of the Law School and the Economics Department at the University of San Carlos? What explains the continuation of repression? In Guatemala, peace was imposed. The military lives off war, but they knew the conflict couldn’t last forever, and they tried to make sure there would never be any real change in the country; they wanted to destroy everything intellectual, any possibility that Guatemala could rise up and become a better country. The Diario Militar case shows how they killed professionals, students. That’s where you start to understand what the objective of the military really was.

The new constitution finally took effect in 1986, on January 14, and that constitution created what are known as “postulation commissions,” with the goal of involving the University of San Carlos and the Guatemalan Bar Association — some of the few institutions remaining after the armed conflict — in the political life of the country. But the real objective was to break the educational system in exchange for political gains, because giving San Carlos the power to participate in the election of the Attorney General, the magistrates of the Supreme Court of Justice, the magistrates of the Constitutional Court, the Public Defender’s Office — up to 53 public positions in total — meant that the political parties started focusing on controlling the university, which is now in the business of trainings voters, not professionals. And wherever they made inroads into the university, there was power to be grabbed. It was a strategy in stages, where sectors of political power took over the university, which had already been weakened, because they had killed everyone.

Some say that, in just the few months since you left the judiciary, the Death Squad Dossier case is already facing setbacks. Do you have that impression as well?

Definitely. That’s why the case raised my profile so much.

Do you mean that you were forced to leave the court and the country because of that case?

There’s a larger context. There are other trials. I had the burning of the Spanish embassy case, Sepur Zarco, the genocide trial… It’s not like they had a lack of reasons. But the Death Squad Dossier got the attention of certain elements in the military, and it’s the one that made me feel pressured to leave the country. This explains why Toribio Acevedo was released from pretrial custody as soon as I tendered my resignation. That tells you a lot about why I was pressured to leave.

What are your thoughts on Acevedo’s release from pretrial detention?

A judge has the power to grant pretrial release. That’s not in dispute. The problem is, how is it possible that [senior anti-corruption prosecutor] Virginia Laparra can be imprisoned for four years and meanwhile, someone accused of crimes against humanity, extrajudicial execution, torture and enforced disappearance is granted pretrial release? It’s totally unbalanced. Besides, in cases like this one, the number of victims must also be taken into account, and the fact that, in the Death Squad Dossier, the victims are extremely vulnerable people. We’re not talking about one, two, three deaths. The dossier has 175 photos; and these photos don’t just represent 175 murders, disappearances or cases of torture, because for each one of those faces, there was a wife, children, loved ones who endured their death, torture, disappearance. Releasing the accused from pretrial custody puts survivors and witnesses at risk.

Do you think they’re dismantling the case?

Of course. And not only the Death Squad Dossier case, but all the cases I was involved in. Let’s start with the basic issue: who else could they put in charge who would understand the Cooptation of the State case, considering it took me years to begin to understand all of its details and ramifications? And the same for the La Línea [customs fraud] case: the people who are left in charge don’t even understand the process. What possible future could the case have under these conditions?

That was the objective. Who worked with CICIG? The FECI. Well, they took them out first. They took Juan Francisco [Sandoval] out, and two years later, the FECI was completely dismantled. But the judges remained, and that’s why Érika [Aifán] was the first to leave. Then came my case, precisely because our courts were created expressly to hear cases involving criminal structures.

What has living in exile been like for you?

It’s hard. Only those who have experienced exile can understand it. I left my country after 23 years when my only income was a monthly salary. I have absolutely nothing, because in those 23 years I could only do so much. But imagine leaving with just a suitcase, leaving behind your books, your clothes. To be in another country, not even having a sweater, a shirt, with all your things at home, it’s.... It’s as if a part of your heart is still there.

You’ve been to Europe, you’re passing through the United States, and heading to Costa Rica, but you haven’t found a place to settle down.

No. One option is Spain. There’s also Mexico or Costa Rica. But it’s not easy, because I’ve been offered a stipend to study, but that would only keep me entertained. What I need is to work, to do some consulting, research, find a stable job so I can bring my family and my son, who are still in Guatemala, with me. To decide where to settle down before doing that would be irresponsible.

Is your family safe in Guatemala?

No. And the problem is that the more I speak up, the more danger I put them in.

Blackmail and threats seem to follow you wherever you go.

Yes, definitely. I’ve been out of the country for five months and cars keep showing up at my mother’s house. They park outside, taking pictures of people coming in and out. And there are people in my family who have been forced out of work. It’s as if we were still at war: If you’re one of their targets, they won’t be satisfied with just attacking you; they want to destroy everything around you.

Have you spoken with other exilees from Guatemala?

Yes, all of them.

What have they achieved by leaving?

Look, international cooperation is ending. There’s no more support for the people who are outside the country, nor for those who are detained, nor for those who are still in Guatemala and who it’s clear will also need to leave. There’s a lack of interest at the political level to force Guatemala to return to the rule of law.

You’ve been in Europe for a few months. Do they understand what’s happening in Guatemala?

They understand what’s happening, absolutely. The exclusion of the MLP made them see exactly what kind of democracy we’re talking about. Yes, they’re aware, but they have other priorities. The challenge is to get Europe and the United States to take up the issue, not just of Guatemala, but of Central America more broadly, which is a ticking time bomb.

What’s been your takeaway from the meetings you’ve had in Washington?

It’s even worse here, because they understand the situation even better, but the challenge is to convince them that, without their support, conditions in Guatemala will never improve.

What kind of support?

With sanctions on economic powerholders. And on the military. The United States has the tools, but refuses to use them.

Why?

The United States already has so few allies in Central America, and they don’t not want to lose Guatemala. That’s why they’re asking themselves how far it’s prudent to go. And there are a lot of international pressures. There’s the issue of China, Russia… The landscape is quite complex, and they’re afraid that, if they take stronger actions, Guatemala will start leaning toward another power.

A year and a half ago, you made a visit to Washington with Érika Aifán and other judges. They were still on the bench, but the possibility that the pressure would increase and they would end up in jail or exile was already very present. During one meeting their compatriots were offering them words of encouragement and jokingly saying, “We don’t want to see you around here.” At the time, did you believe that this situation could be avoided, or did you think it was only a matter of time?

With the way the situation was developing, I knew it was just a matter of time. That’s why exile hits so hard, because you’re already experiencing it even before you leave, and you start to think about the people around you, and you start to reflect…. It’s like if a doctor tells you what day you’re going to die. The mind and body freeze, and you wish you could stop time. Then you… [Judge Galvez starts to cry, but holds his gaze and continues talking]. There are times when you start to think that maybe it was a mistake to believe in the justice system at all. Because you get wrapped up in what you’re doing, and you detach yourself from reality. The cases are your whole world, and you wake up, get ready for the day, walk, and then everything is the case, the case, the case. You dream about the case, and you no longer have time for anything or anyone else.

The truth is that only those of us who are experiencing it can understand it. One would think, why ask for help if we can do it ourselves? How sad. Why do things have to be like this? But we have to admit it: 'Given the condition the country is in, no, we can’t do it alone.'

*Translated by Max Granger