The trial in Guatemala of journalist José Rubén Zamora is a tale of a defense up against the ropes in a process plagued with irregularities. In the nine months since his capture in July 2022, the judicial file of the renowned journalist and businessman has passed through the hands of seven private defense attorneys and two public defenders. Four were detained for alleged crimes committed in Zamora’s defense; two of these accepted charges of obstruction of justice. A fifth attorney abandoned the country. The trial has broken elPeriódico, the daily newspaper that Zamora founded almost three decades ago.

When the public trial began on May 2, the two new attorneys who accompanied Zamora were the backup of the backup of the backup defense team. They had been hired by his family barely two weeks before and had only had access to a third of his 800-page judicial file. On May 11, after six days of testimony and cross-examination, both of the defenders had left the case. The next day, May 12, public defender Fidenza Orozco García was assigned as his ninth attorney.

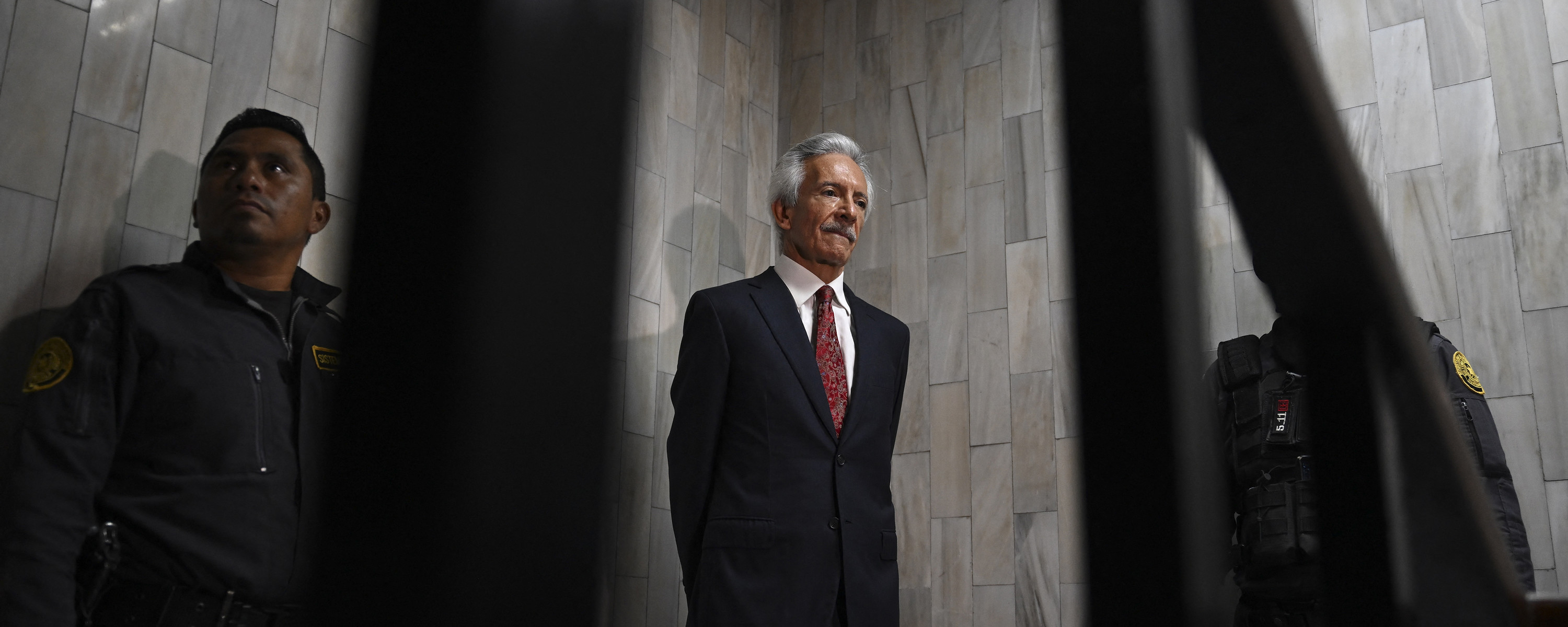

Zamora, 66, is accused of laundering money, peddling influence, and blackmail with confidential judicial information. His historic prosecution has placed an international spotlight on growing attacks against the press in the Central American country. The founder of elPeriodico could face up to 20 years in prison on the count of money laundering alone. The trial, which has been widely scrutinized internationally for procedural irregularities, could last until the last week of May, estimates Rafael Curruchiche, head of the Special Prosecutor’s Office against Impunity (FECI), who was sanctioned by the U.S. State Department in July 2022, accused of corruption, and is leading the case against Zamora.

The attorney general of Guatemala, Consuelo Porras, is in the ‘Engel List’ of corrupt or anti-democratic actors, too. In February 2022, an El Faro English investigation revealed that Porras and Curruchiche dismantled and obstructed a special team of prosecutors who were investigating possible bribes of President Alejandro Giammattei. The Public Prosecutor’s Office has called this and other journalistic reports on the matter “false information.”

The FECI has also accused the journalist of conspiring to obstruct justice in a second case derived from the original, alongside the first two attorneys who represented him. His family has denounced harassment and threats that they say have obstructed their search for legal counsel. International legal observers have reported a “persecution” or “criminalization” of the defense.

Raúl Falla, private plaintiff in the Zamora case and member of the Foundation Against Terrorism (FCT), a far-right organization that in the last two years has propelled lawfare against dozens of anti-corruption prosecutors and judges now in prison or exile, openly admits that there has been a “criminalization” of Zamora’s attorneys, “but with evidence.”

The Zamora trial has provoked elPeriodico’s economic collapse, including the laying-off of 80 percent of staff and the shuttering of the print edition in December. Zamora testified on May 3 that newsroom director Julia Corado, three journalists, and two columnists are in exile. In the morning on Friday, May 12, the paper —which since its founding in 1996 has left a broad record of corruption, drug trafficking, and transitional justice cases stemming from the internal armed conflict— announced that it will print its last edition on Monday, May 15, under the strain of “persecution and political and economic pressure.”

“For many years elPeriódico revealed information that corrupt sectors of political, economic, and military power and criminals did not want to be made public,” said Marielos Monzón, a distinguished Guatemalan journalists and one of the primary spokespersons of the local press freedom movement No Nos Callarán (“we won’t be silenced”).

“They are not prosecuting Zamora as a businessman, as Rafael Curruchiche tried to justify. They are persecuting him for being a journalist,” she added. “They are sending a message to all of us journalists and independent news outlets in Guatemala: ‘If we did it to him, an emblematic, award-winning journalist, we will do the same to you.’”

“The de facto powers of Guatemala… are outlining the route that they will follow. They want a dictatorship of silence and impunity.”

A defense under scrutiny

The charges against Zamora’s legal counsel began on the first day of pre-trial hearings on Aug. 3, 2022, just five days after his arrest. The FECI announced that it would accuse Zamora and defense attorneys Mario Castañeda and Romeo Montoya of conspiring to obstruct justice.

Falla and Ricardo Méndez Ruiz, president and founder of the FCT, voiced support for the decision. Falla is also the legal representative of state witness Ronald García Navarijo, a former banker whose testimony against Zamora served as the basis for prosecutors to mount a case and arrest him within 72 hours.

“In the statutes of our foundation, we are obligated to always pursue justice,” Méndez Ruiz told El Faro English. “This is a highly relevant case for us.”

When pre-trial judge Fredy Orellana indicated to Castañeda and Montoya that they should leave the case due to the conflict of interest posed by the new charges of obstruction of justice, they had only spent three days on the case.

On August 8, Zamora appeared in court represented by Costa Rican lawyer Christian Ulate, a former legal coordinator of the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG). Ramón Zamora, one of his sons, told El Faro English that Ulate resigned on September 14 and left the country. “He told us that he was warned of pressure on the Bar Association to revoke his license to practice law in Guatemala,” he said.

Last October, Carlos Aquino, secretary of the Bar Association, said that he was unaware of any pressure. But according to José Zamora, another of the journalist’s sons, almost all of Ulate’s cases in Guatemala began to fall apart, which the lawyer interpreted as a threat and a message.

Exiled judge Miguel Ángel Gálvez asserts that Ulate visited him two weeks before resigning: “He [Ulate] told me that they had been following him since he took the case, and that they had started to intimidate him.”

On October 3, public defender Sandra Eugenia Morales García picked up the case. Just three weeks later, on October 22, the former head of the Guatemalan tax authority SAT, Juan Francisco Solórzano Foppa, presented himself in court as Zamora’s fifth representative.

Toward the end of last October, Solórzano Foppa presented new evidence in an effort to refute the money laundering charges against the journalist. Two months before, Zamora had initially said that 300,000 quetzales ($40,000 USD) confiscated by the FECI in his house were from two businessmen who asked for anonymity for fear of government reprisals if it was known that they were financing elPeriódico. Solórzano argued that one of them, Alejandro José Girón Lainfiesta, had also purchased a painting from the journalist, accounting for a portion of the money. According to Zamora, the painting sale was not mentioned before because pre-trial judge Orellana refused to admit the evidence during discovery.

“He [Girón Lainfiesta] bought the painting on July 25, 2022,” said Zamora, asserting that he received 240,000 quetzales in cash previously withdrawn from a bank. His previous attorney, Ulate, had cited the fact that the money was bound with currency bands as proof that it could not have an illicit origin. “You don’t launder money already banked,” he argued. Zamora claims that another 25,000 quetzales in banded cash confiscated by the FECI came from a check that elPeriódico had submitted at Banco Industrial, and another 35,000 from emergency savings.

Méndez and Falla hold that the bands do not necessarily rule out illegal origin, though they have provided no proof that they were obtained illicitly.

Rather than a formal contract, Zamora holds that he signed a written statement on the painting transaction because Girón paid him 40,000 quetzales at the time of sale and another 200,000 two days later, with the promise to pay the remaining 60,000 the following month.

In October, according to José Zamora, Girón grew worried: “He [Girón] wanted to cover himself,” so he drew up a document to register the transaction. But Girón dated the document earlier, and the FECI seized this fact to accuse Zamora’s defense attorney at the time, Solórzano Foppa, of obstructing a judicial action. (Girón’s bank account, according to courtroom evidence, effectively shows the withdrawals of cash on July 25 and 27.)

“The handling of the painting was finished before he [Foppa] stepped in as my lawyer,” stated Zamora.

Méndez Ruiz said that the fact that the sale of the artwork, a source of part of the money, was not mentioned from the start of the trial, indicates that it was a “machination” by Zamora, his son Ramón, and Solórzano Foppa after the journalist’s arrest. Girón was indicted on these grounds. While Zamora said that he sold the painting on July 25, four days before his detention, Girón testified that he first paid money for advertising, only to later accept a painting in exchange.

Zamora said on May 9 that he learned that his son Ramón was facing a warrant for his arrest, but Juan Luis Pantaleón, spokesperson for the Public Prosecutor’s Office, told El Faro English that no such order existed. Zamora added that FCT had published a photo of his son on social media with the word “corrupt” written across his face.

Ramón was left to administer elPeriodico since his father’s arrest. He left the country in April.

According to Zamora’s version, he later asked his friend-turned-state witness García Navarijo to deposit the money in one of his own accounts and issue a check for the same amount, for Zamora to then deposit in elPeriódico’s account without leaving a trace of the newspaper’s original financiers.

The banker then allegedly reported to the FECI that the journalist had threatened to publish compromising information on him if he did not issue the check. This assertion is the basis for the entire case against Zamora: The accusation of money laundering hinges on proof of illicit origin of the money; blackmail would be an illicit origin.

Arresting the defense attorneys

On January 19, the FECI announced that one of first defense attorneys for Zamora, Mario Castañeda, had turned himself in.

On March 3, Solórzano Foppa and Justino Brito Torres resigned from the defense at Zamora’s request, in a fleeting effort to avoid being criminalized. Seven weeks later, on April 20, both were arrested under authorization of Judge Jimmi Bremer.

Five days later, Romeo Montoya also turned himself in. He and Castañeda accepted charges of conspiracy to obstruct justice and received commutable prison sentences, just like Flora Silva —the former head of finances for elPeriódico, convicted as complicit in laundering money— did in December. Solórzano Foppa and Brito are still in jail with ongoing cases.

The evidence submitted against Montoya and Castañeda is the recording of a conversation between the two lawyers, Silva, and García Navarijo dated Aug. 21, 2021. In it they discuss how to register in the paper’s accounting a loan in the form of a check for 200,000 quetzales that Zamora received in 2013 from the Workers Bank (Bantrab), where García Navarijo was an executive. Zamora provided a statement to FECI investigators about that check in 2018.

In the case of Costa Rican attorney Ulate, Falla insists —wrongly— that only natural-born Guatemalans can practice law in the country. “He [Ulate] left [the case] because he felt pressured and indicated that the Foundation was going to persecute him. Yes, we were going to make moves with the Bar Association, because we weren’t particularly fond of how he acted.”

“What happened with Solórzano Foppa and Justino Brito Torres? We criminalized them, too!” continued Falla. “The Public Prosecutor’s Office established that the contract for the painting to accredit the origin of the money was false.” Falla cites the fact that the contract was not written July 25, 2022, but in October, when the journalist was already incarcerated.

Zamora’s son José asserts that in a private transaction a formal document is unnecessary. “Moreover, the state intervenes only when an interest of the state has been violated,” he said. “Which state interest has been violated here? None.”

The Zamora family hired its last two private defense attorneys, Ricardo Sergio Szejner Orczyk and Patricia Guillermo De León De Chea, the same week that Solórzano and Brito were arrested. On May 2, when the public trial began, they had spent only 11 days on the case. “They stayed silent from the time they signed on [as legal counsel]. They did not want anyone to start harassing them,” José Zamora told El Faro English.

The silence did not last. An anonymous Twitter account revealed on April 30, two days before the hearings, that Patricia Guillermo would represent Zamora. The publication, citing supposed sources in the Judicial Branch, included a clip from U.S. war movie Saving Private Ryan, in which a sniper takes a bullet through the eye.

The beginning was rocky. “He has changed attorneys and the documents haven’t been left in order; everything has been so abrupt,” said Guillermo. Szejner added that “because of the haste” they had received scant access to the evidence.

Both attorneys say that, as the previous defense attorneys Solórzano Foppa and Brito Torres were in jail, they received only a part of the file in disarray, lacking videos and voice recordings. In a May 4 hearing, FECI prosecutor Cynthia Monterroso offered to provide the rest of the file on May 10, claiming that she was too busy before then.

The new “friendly” defense

Guillermo and Szejner’s first arguments reflected their little time to study the case. On May 2, Guillermo began her opening statement with a reflection on “the co-optation of the Guatemalan state by organized crime in the year 2000.” She told El Faro English that she tried to explain that money laundering charges require a criminal structure, and how the arguments against Zamora lack that element.

But Oly González — the same judge of the Eighth Tribunal of Criminal Sentencing who convicted former FECI prosecutor Virginia Laparra— prevented her from doing so. At first, she listened impatiently, leaning her face against the palm of her hand, a gesture that became frequent in the coming days. She then interrupted Guillermo to remind her that “the opening allegation is an argument about the facts [of the case].” In the afternoon, she scolded the defense attorney for her “lack of argumentation.” Guillermo, who has litigated for at least 40 years, responded curtly: “My apologies for not doing so in the way that you ask.”

Zamora, thin and dressed in a navy blue suit with a red and gold paisley tie and thin spectacles, timidly raised his hand twice in the opening arguments to add details about irregularities in his arrest and prison conditions. “This court cannot admit anything that you have said,” interrupted Judge González. “You will have the chance to testify if you wish.”

During the recess of the fifth hearing on May 9, the defense’s fortune again worsened. Szejner asked for water. Zamora asked him if he felt well. Hours later, he went directly to the hospital, where he was diagnosed with a crisis of hypertension and severe arrhythmia. According to his medical record reviewed by El Faro English, a doctor recommended that he cease “excessive work and nervous tension.” By 4 p.m. Guillermo was left as sole counsel. Eight days had passed since they presented themselves to the court.

On May 8, two days before Guatemalan Mother’s Day, Zamora asked her to request that the court permit a conjugal visit by his wife in the Mariscal Zavala military prison. “I cannot give orders to the Prison System. It is something that you must request,” said the judge. Guillermo, who was director of the Prison System from 2004 to 2005, replied that, as a superior court officer, the law does empower González to suggest a course of action in special cases like that of her client. “I already told you that I cannot intervene,” answered the president of the tribunal.

The last resignation

From the first day of the trial, Guillermo knew that she was walking a tightrope. “We are going to make our arguments, but never belittle any of the sides, nor attack,” she said. “The atmosphere must be friendly.” In a diplomatic gesture to one of the private plaintiffs in her opening argument, she said: “I respect the work of the Foundation Against Terrorism.”

The tone of her counterpart was quite different: Minutes before the public hearing began, Falla posted to Twitter a selfie at the foot of the court with two colleagues from the foundation, announcing their arrival at the “start of the trial against the money launderer, extortioner, and influence peddler @ChepeZamora.”

When asked during a recess about the criminalization of Zamora’s defense, Guillermo marked her distance from her predecessors: “There have been errors, crass errors,” she told El Faro English. “If you make a mistake, the other side attacks. One must be very careful with what is said. You cannot offend the structures, nor attack. You can only defend.”

Guillermo said that the guilty pleas of Silva and attorneys Castañeda and Montoya would factor into her strategy. “These are facts that clearly affect the main case,” she indicated. “But it’s important to clarify how they declared, and in what context… The judicial context has a great deal to do with how the guilty pleas are established.”

Méndez Ruiz asserts that the guilty pleas weigh heavily on Zamora’s case “because they were convicted.” But, during the trial, the judge prevented Monterroso, the prosecutor, from asking Silva about her process and what type of sentence she received. “Do not answer!” she interjected, in a suggestion that Silva’s conviction was not pertinent to her ruling.

On May 11, two days after Szejner left the case, Guillermo also dropped out, this time at Zamora’s request. Early in the day, she had said that the case was not one of the most difficult she had worked on. “I imagined it would be even more difficult in terms of the evidence, but the witnesses and examinations that have been annexed do not have much weight.”

Guillermo said that during the May 11 hearing her client had proposed that she resign due to the hostile treatment from the court against the defense, but that she had declined. “This is impossible; they are treating you so poorly,” Zamora told her, in reference to interactions with Judge González. “I told my esteemed José Rubén, ‘I’m brave; I don’t care if they humiliate me.’”

“He wrote me a note saying that if I resigned due to hostility from the court, I would be fine, and that he, on the other hand, would demonstrate the system’s animosity toward him. I replied, ‘Let me present to you on Sunday the conclusions that I’ve been working on.’ But he didn’t answer.” In the final minutes of the hearing, Zamora asked for the change of attorneys, catching Guillermo by surprise. In that context, the judge postponed hearings until May 18.

When the hearing ended, journalists present reported that Zamora attributed his request to his inability to pay Guillermo.

According to José Zamora, the family thinks the defense could have made stronger arguments since August, and that his father wanted to avoid the criminalization of the attorneys, but also that they had had trouble paying legal fees.

The night that she resigned, Guillermo tweeted: “Today Engineer Zamora informed [me] that the Public Defender’s Office would take over his case. J. Rubén, I am a renowned lawyer practicing criminal law, not your accomplice or defender of other causes.”

Hours later, on May 12, elPeriódico announced it would publish its last edition on Monday, May 15, after 27 years of publication. Last November they ran their final print edition and laid off 80 percent of staff. Ramón Zamora told El Faro English last year that government pressure against financiers and advertisers had led them to withdraw their contributions to the outlet.

The defense of Zamora, arrested nine months ago as he struggled to obtain funding to keep the elPeriódico afloat, remains rudderless. The case against him has spelled ruin for the leader of investigative journalism in Guatemala since the end of the internal armed conflict in 1996. Eight defense attorneys have come and gone, leaving Zamora no closer to being released to revive his newspaper.